Recent evidence from the US suggests that allocating government funding for public libraries increases children’s engagement. The result is a tangible improvement in children’s intellectual skills.

By studying the US’s experience and adapting it to their own local context, Gulf countries may reap considerable rewards from increasing investment in public libraries.

Anyone who has seen the dramatic change in the Dubai skyline from 1970-2020 is keenly aware of how rapidly the infrastructure has improved in the Gulf countries after discovering oil and setting up strong national agendas.

Prior to the availability of these resources, the harsh, arid climate meant that high population densities were unsustainable, placing a low ceiling on the value of large-scale infrastructure investments. Moreover, the limited means available to the governments meant that they could scarcely afford to spend big on projects such as sophisticated transport networks, in contrast to what was commonly unfolding in the western world during the first half of the 20th century.

As a result, when the high oil prices of the 1970s did present an opportunity for effecting an unprecedented leap in the quality of infrastructure, there was much ground to make up. Public libraries did not secure a high position in the list of priorities, with governments preferring to focus on infrastructure that was more critical and with a more easily perceptible economic return, such as power stations and airports.

As an illustration, according to data from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, in 2022, the five Gulf countries for which data is available all had less than 0.5 public libraries per 100,000 people, as compared to more than five public libraries per 100,000 in the UK and US.

The limited attention paid to public libraries was reinforced by the meagre academic literature estimating the benefits of investing in such institutions at the time, as it meant that the western consultants who often advised the governments on optimal infrastructure investments had few figures to lean on when potentially extolling the virtue of allocating funds to public libraries.

More specifically, the discipline of economics underwent a methodological revolution after the Second World War due to simultaneous advancements in data availability, statistical modelling and computing power. This allowed economists to demonstrate the potentially impressive returns associated with allocating public funds to roads, hospitals and universities.

However, as scholars Dr Gregory Gilpin (Montana State University), Dr Ezra Karger (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago) and Dr Peter Nencka (Miami University) explained in a recent paper on US investments in public libraries, a variety of idiosyncratic methodological challenges meant that economists did not try to estimate the economic returns associated with investing in public libraries. As a result, the case of supporting such institutions has traditionally rested on appeals to a nebulous return associated with having a more bibliophilic society.

Yet in their 2024 paper, The Returns to Public Library Investment, Dr Gilpin and his co-authors plug this intellectual gap – at least in the case of US public libraries. They gather 21st-century data on capital expenditure in American public libraries and tie this information to two other groups of data: first, data on children’s activity in those libraries, such as the number of visits and books borrowed; and second, data on children’s intellectual abilities, provided by their performance in standardised tests.

The results constitute a rare and unprecedented demonstration of the returns to investing in public libraries. The economists were able to show that the libraries that experienced increases in their capital expenditure were able to attract greater numbers of local children and to circulate a larger number of books among them. Moreover, this translated into substantive improvements in their scores in standardised tests.

Of course, fixating on outcome measures such as higher SAT scores would probably make most supporters of public libraries cringe. They would argue that much of the benefit accruing to society cannot be gauged by means as primitive as children’s responses to multiple choice questions. Instead, having a more learned and worldly society that prefers losing itself in bookstacks to playing video games is the real benefit of an effective system of public libraries.

Nevertheless, ignoring the easy-to-measure economic returns is no longer an option in the 21st-century model of public administration. Countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE use such metrics as tools for holding civil servants accountable and maintaining the efficacy of their public spending. Accordingly, the conclusions of the study by Dr Gilpin and his colleagues should persuade countries to consider increasing their investment in public libraries.

There is an important qualification for the Gulf, however, which is the need to replicate the methods used in the study, but for the data that will be generated locally – should the governments be convinced of the benefits of investing in public libraries. How a library affects children living locally depends crucially on many cultural factors that differ between countries such as the US and Kuwait.

For example, if attending events at public libraries depends heavily on children being able to walk to their local book repositories and participate autonomously, the local climate during summer months in the Gulf could undermine an important link in the causal chain, as the heat would leave children house-bound. Similarly, if the rate of output of books in the Arabic language is significantly lower than in the English language, then children in the Gulf will have fewer options of books to engage them, potentially blunting the returns associated with investing in public libraries.

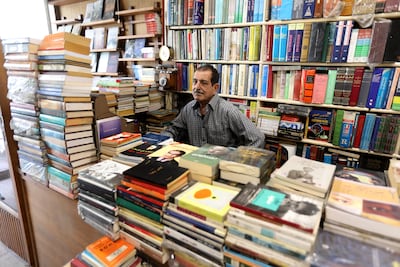

Baghdad’s eighth-century House of Wisdom demonstrates that the region’s peoples are no strangers to the value of investing in libraries. However, nearly 800 years have passed since the Mongol armies filled the Tigris River’s waters with the ink of books pillaged from the medieval wonder. And in that time, societal appreciation of the value of libraries has arguably waned, as reflected in falling scores in the reading component of standardised international tests.

The Mohammed bin Rashid Library, King Abdulaziz Public Library and Qatar National Library are fine examples of what already exists, but the region will only benefit with many more like them.

The publication of a study that confirms the returns to investing in public libraries provides the Gulf countries with a timely opportunity to consider investing in these types of institutions, with an eye on a more educated and worldly generation of children.