A year ago, few could have predicted that a ground war would return to Europe. Fewer still entertained the notion of a possible nuclear conflict on the continent. Today, with Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine approaching its one-year anniversary, the thinking on the latter has shifted, yet without the panic that once accompanied the mere mention of nuclear weapons.

This, however, does not mean that fears of a nuclear war are completely dispelled. Decision-makers in western capitals will be listening carefully to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s speech on Tuesday to mark the Ukraine war anniversary and adjusting their nuclear calculus accordingly. But threats and tensions are one thing; mobilising nuclear assets is entirely another. Officially, the US continues to warn against the dangerous consequences of any use of tactical nuclear weapons, as its leaders know full well that Moscow will not hesitate to use them if the equation of the war changes.

Key Nato members are attempting to persuade China to oppose any use of nuclear weapons by Russia. During his visit to Beijing late last year, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Chinese President Xi Jinping together announced their opposition to the use of nuclear weapons in the Ukraine war. Following the Munich Security Conference over the weekend, Wang Yi, China’s top diplomat, will head to Moscow to prepare for a summit, possibly in April, between the leaders of the two countries. It is worth recalling that Russia reportedly delayed its Ukraine operation after Mr Putin’s visit to Beijing for the Winter Olympics early last year. A year later, China remains unwilling to support the war.

Worryingly, some assessments state that if the Russian leadership feels it must not be defeated at any cost, including the cost of using nuclear weapons, China might be unable to stop it. Beijing could find itself in a dilemma: on the one hand, it does not want a Russian defeat in the war given Moscow is a partner on the world stage; on the other, the use of nuclear weapons is detrimental to all.

Military escalation in the coming weeks is likely to intensify, as Nato powers insist on shifting the war equation in Ukraine’s favour. Russia, too, is likely to launch major offensives to overturn the current stalemate in its favour. And as both sides plan their respective offensives, Mr Putin’s speech could give the rest of the world an idea on what steps could determine the course of the war.

Meanwhile, there have been moves behind the scenes to create a forum to launch talks between Russia and Ukraine and its backers, to secure temporary agreements and security guarantees, but not necessarily to reach the currently impossible goal of a peace agreement. These efforts are being made in preparation for the day after the major battle, namely the offensives of the two sides, which may not conclude with one side winning and another losing.

This week, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko said European powers have sent messages to Minsk requesting its mediation, expressing a desire to end the conflict. Some of Mr Lukashenko’s efforts appear to be unserious, such as his invitation to US President Joe Biden to come to Minsk, expressing his willingness to organise a meeting between him and Mr Putin in the Belarusian capital. But Mr Lukashenko has repeatedly denied that his country will join the war alongside Russia, stating he would not order his forces to fight unless his country is attacked first. This is reassuring news, and his mediation could be met with some acceptance while he is keen to improve his relations with the West.

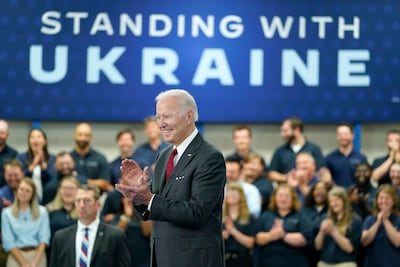

Mr Biden will visit Poland on Monday and Tuesday, where he will meet the leaders of the so-called Bucharest Nine, a group of nine Nato member states in Eastern Europe. His visit carries important political implications that could be translated into military scenarios if Moscow finds them too provocative. Intimidation plays an important role in the psychological warfare being waged by both sides, which poses additional risks.

There is also the element of calculated provocations, such as the US statements suggesting Washington supports Ukrainian strikes on Russian military targets in Crimea. US Undersecretary of State Victoria Nuland said this week, in reference to this issue, that “these are legitimate targets, Ukraine is hitting them and we are supporting that”. For Russia, which annexed Crimea in 2014, the Black Sea peninsula carries significant historical and strategic value.

A year since the war began, the question remains as to what Moscow’s exit strategy is. It is unable to backtrack from the corner it backed itself into, by proceeding with its operation. One could argue that it decided to blow up the international system to reshuffle the deck and negotiate the birth of a new system.

One could also argue that the West lured it into the predicament it finds itself in. After all, the US had verbally pledged to not expand Nato membership – after the late Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to dissolve the Warsaw Pact – then reneged on its pledge. Nato knew well that any attempts to bring Ukraine into its alliance would be provocative to Moscow, especially as it risked altering the balance of power between Russia and the West.

Ultimately, however, it is Moscow that is responsible for falling into the trap. And today, it is paying a heavy price for its mistakes. The West has dropped an iron curtain on Russia through sanctions that have adversely affected its economy, paralysed its banks and corporations’ financial global transactions, and undermined its oil and gas and technology sectors. Western leaders might be betting on a protracted war weakening Russia. Were this to happen, Nato would emerge as the victor. Over the past year, it has become stronger and more coherent along with Ukraine.

All this, however, could be upended by the unexpected, or by decisions – including to use nuclear weapons – being made in Moscow and some western capitals. All eyes will be on Mr Putin’s Tuesday speech and what might materialise on the battlefield thereafter.