Imagine that a group of litigants took the US government to court in Russia, and won a ruling that they were owed billions of dollars over an agreement signed in the early 19th century – on the grounds that Alaska belonged to Russia before 1867. Similarly, what if the Greek government were determined by courts in Turkey to owe a huge sum of money over an historical contract, the argument being that, because Greece was then in the Ottoman Empire, Turkey would be the right place to deal with this issue? Both cases are unthinkable, and the latter could bring the combustible Greco-Turkish relations to the brink.

Something very similar to this, though, has just happened to Malaysia. Last week, it led to a bailiff serving asset seizure notices at the Luxembourg offices of two subsidiaries of Petronas, Malaysia’s state-owned energy giant, and sent panic through the government that national assets anywhere in the world could be at risk.

The asset seizure notices were delivered as the result of a ruling that Malaysia owes $14.9 billion to a group who claim to be the heirs of a sultanate that has not existed since 1915, and is an unwelcome example of how the international legal system can still be entangled by almost-forgotten relics of colonial history.

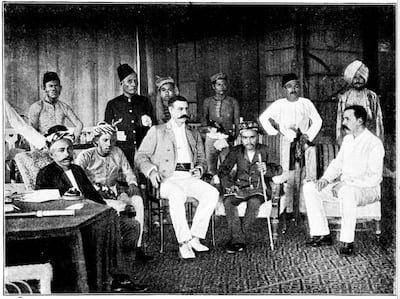

The story begins in 1878, when the then sultan of Sulu, a group of islands in western Philippines, signed an agreement that allowed the British North Borneo Company to take over a chunk of land in what is now the Malaysian state of Sabah. Any dispute over whether it was a lease or a cession should have been cleared up by a subsequent treaty in 1903 that confirmed the “cession”. North Borneo later became a British colony, and in 1963 agreed to become part of the newly created state of Malaysia.

Up until nine years ago, Malaysia continued paying an annual cession payment of 5,300 ringgit ($1,190) to descendants of the last sultan, who died in 1936. But in 2013, a 235-strong group associated with one of the pretenders to the defunct sultanate “invaded” Sabah – which sounds like a joke, except 56 of the militants died, as did 10 Malaysian security force personnel and six civilians.

The sum of money that could reasonably be claimed, therefore – if it was not deemed fairly forfeited after the attack on Malaysia – may be around $13,500, with interest. Hardly a sultan’s ransom. The heirs and their lawyers, however, have brazenly taken this as an opportunity to demand compensation for the vast mineral wealth in Sabah that nobody was aware of back in 1878.

Tommy Thomas, who was Malaysia's attorney general when the case was proceeding, recently said that the heirs told the Malaysian government “that they tried to go to the UK” as the former colonial power in North Borneo. "The UK chased them away. The UK said: ‘We have nothing to do with this, go to the courts of Malaysia’".

The heirs then went to Spain, the former colonial rulers of the Philippines, where the Madrid High Court appointed an arbitrator, Gonzalo Stampa. According to Mr Thomas, Malaysia contacted the Spanish authorities, and “the Madrid court agreed with us and set aside everything” – whereupon Mr Stampa took the case to France, which likes to call itself “the home of international arbitration”. In February, the huge sum was awarded, a judgment the French Court of Appeal ordered stayed on July 12 – except by then, the bailiffs had already sprung into action in Luxembourg.

The story is even more convoluted than that, and if it seems strange that the case moved to France, the explanation given by one involved source to a Malaysian paper, The Edge, was that an “arbitration is like a plane – once it takes off, there is no way the control tower where the plane took off can dictate what happens”.

The Malaysian government is confident that it is in the right. Perhaps a relatively small sum may be due to the heirs, but nothing remotely close to $14.9bn. And that is being generous, because many historians dispute that the Sulu sultanate ever had any legitimate claim to the land in Sabah in the first place; in fact, they argue, it belonged to Brunei.

"Sulu never had a treaty or a title deed from Brunei, and no record or evidence exists of Sulu ever possessing or governing North Borneo,” says Bunn Nagara, convener of the Sabah Malaysia Study Group. Brunei ceded the area to the British North Borneo Company in 1877. “Sulu was asserting a claim to the territory and had a reputation for raiding coastal settlements, so as an insurance policy the company made another cession agreement with Sulu."

In short, the heirs were lucky to receive cession payments for a land that may never have been theirs to begin with for so long. Until recently, all this was mostly a matter for historians, although as Mr Bunn points out, “the claim remains a very populist issue in the Philippines, unsupported by the facts as it is. Previous presidents such as Corazon Aquino and Gloria Arroyo, who tried to mitigate Manila’s claim on Sabah, have been accused by some as traitors".

Now, however, while the Malaysian government told the Financial Times that the award’s suspension in Paris was grounds for other countries to refuse its enforcement, the heirs’ lawyers in London insisted that “the seizure process is a rolling programme”.

Malaysian officials are taking measures to protect assets abroad, but the worry at the moment is that the heirs’ lawyers, who are believed to be backed by a major litigation fund in London, “can pick from the other 167 jurisdictions that are party to the New York Convention on arbitration, and then Malaysia will have to show up and say we have a stay from the Paris Court of Appeal", says one involved in how to combat this action in Kuala Lumpur. “What’s the limit to this? Should European countries have any role in these kinds of disputes? Shouldn’t colonialism have ended already?”

All good points. What this bizarre story shows, however, is that while colonialism may be long gone, its legacy can still be exploited. International law needs to catch up. Ordinary Malaysians do not deserve this attempt to squeeze billions out of them. And somehow, I suspect that deep sympathy for the descendants of the last Sultan of Sulu does not top their lawyers’ list of concerns.