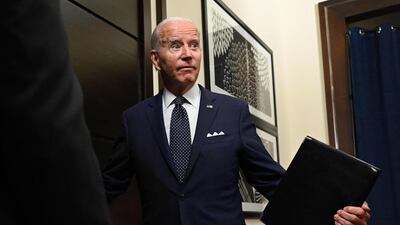

There's much to criticise about Joe Biden's performance thus far. Yet, the 46th US President's sustained unpopularity – close to that of his predecessor, Donald Trump, who he now only narrowly defeats in hypothetical one-on-one races in swing states – is hard to explain.

He's had policy botches, such as the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and major challenges, several stemming from the coronavirus pandemic.

Still, his administration has been relatively scandal-free and stable, with an extremely low turnover rate. The tasks are generally getting done. That some of the bitterest criticism comes from the far left of his own party, which claims to feel betrayed, should bolster his position with the centre and centre-right – but no.

Unless Mr Biden quickly recovers from this year-long bout of historic unpopularity, the causes will be studied for decades. But even now it is clear that the Biden administration's messaging mistakes are well worth a “hot take” consideration as the main suspect.

Take what is certainly the main source of discontent: inflation. The rate is now about 9 per cent annually, the highest since the early 1980s. Americans have not seen such numbers in almost half a century and are angry. For low-income families this means significant suffering, if not calamity. Even those who can afford higher prices are dismayed.

Few Americans care that this is a global crisis largely produced by the pandemic, or that much of the developed world is experiencing even worse rates. Since it has come as an unpleasant shock, all that most Americans want to hear is what you're going to do about it.

But it should not have come as a shock. Allowing it to have been a shock was itself a messaging failure. If the administration seriously believed that the massive coronavirus relief spending at the beginning of Mr Biden's administration – $1.9 trillion in the American Reiscue Plan alone – wasn't going to risk significant inflation, such wilful blindness is its own form of incompetence.

Surely they knew such spending could overheat the economy and contribute to inflationary pressures. Yet they never explained to the public that this spending was needed to stave off a nationwide unemployment crisis and other catastrophes, and that everyone should brace for a potential surge in inflation.

Instead, when inflation hit, the administration promised the problem would go away, and then blamed "corporate greed", and a range of other facile excuses. They were right to make the difficult choice they made. The public should be thanking them for that.

But since they never explained what they were doing, they are getting castigated both for inflation and for the fact that unemployment is so low that businesses are having a hard time finding workers.

More than a year ago, Mr Biden needed to give a primetime address to the nation to bluntly say: "We had to choose between saving your jobs or risking a period of higher prices. We saved the jobs. Now we will all work together to bring down the prices."

Because he didn't, the austerity-like cooling measures required to do exactly that will feel like yet more unnecessary pain. And once again, they’re going to get the blame for everything bad and no credit for what is good.

Mr Biden just experienced another instance where he could have saved himself a lot of unnecessary grief by levelling with the American public early and bluntly. His Middle East trip was roundly criticised in the western media, largely because of his visit to Saudi Arabia and his meeting with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

During the primary and presidential campaigns, Mr Biden vowed to make US outrage at the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi a centrepiece of his policy towards the kingdom and he even spoke of making it "a pariah". That was effective politics, especially with regard to his own party's left flank.

But it was obviously never going to be a basis for US foreign policy. The US-Saudi partnership has endured for almost 80 years because it rests on strong fundamentals, especially maintaining regional security and stability and defending the status quo.

Mr Biden had well over a year to prepare Americans for the fact that he was going to have to repair relations with the Saudi government and the Crown Prince. To help make the case, Mr Biden should have explained that he had indeed taken a range of significant measures to express US anger about the Khashoggi murder, including releasing CIA findings about the killing and enforcing a range of sanctions against implicated Saudi individuals.

Then Mr Biden should have described how, despite these measures, Saudi Arabia has been co-operating with a range of US requests including maintaining a truce in Yemen despite serious provocations from the Houthis, taking in Afghan refugees, extending financial support to US friends in Lebanon and Iraq, siding with Washington against Moscow at the UN, and increasing oil production (without breaking the existing Opec+ agreement) to help control the spike in gas prices, largely caused by Russia's Ukraine invasion.

Eventually, and only at the last minute, in a Washington Post commentary, Mr Biden told his fellow Americans that, whatever his personal feelings, he was elected to protect the interests of the American people and the country and that, therefore, he was going to Saudi Arabia. Coming when it did, it sounded defensive and flimsy instead of the simple truth that it is.

These are just two examples. The international relations analyst Brian Katulis has insightfully catalogued the administration’s extraordinarily muddled messaging on foreign policy – despite its astoundingly successful performance in reviving and revitalising Nato and the Western alliance in Europe to confront Russia and support Ukraine – and the story isn't much better on the domestic front.

It is easy to imagine Republican and left-wing Democratic voices retorting that no amount of skilful messaging could make Mr Biden and his policies look good. But such predictable ideological carping explains nothing.

Unless Mr Biden rebounds relatively quickly and dramatically, a serious and complex explanation for this bout of extreme unpopularity will be required. For now, we can at least be sure that if his administration were not so dreadful at messaging – even when it comes to usually defensible, and sometimes excellent, policies – the president’s poll numbers couldn't possibly be quite this dismal.