The downfall of a spy chief is never an anecdote. In a world of secrets, public dismissals of high ranking intelligence officials always denote failure or a power struggle of some kind – at times both. The removal of Hossein Taeb, the head of the powerful Intelligence Organisation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is no exception. Mr Taeb had been the head of the Intelligence Organisation since its inception in 2009, and had weathered many crises and internal struggles since.

Iranian authorities tried to soften the blow by portraying his removal as some form of “promotion”, appointing him as an adviser to the head of the IRGC, but the picture was clear: Mr Taeb was fired as unceremoniously as is possible in the cloak and dagger world of espionage.

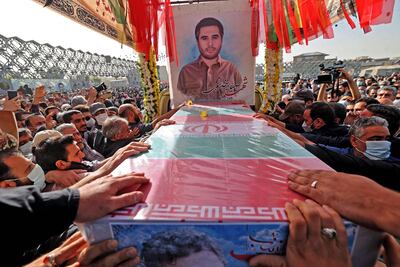

The timing makes it clear that his removal is tied to his failure to protect Iran from an increasingly daring series of alleged Israeli operations on Iranian soil. Over the past weeks, the shadow war Iran and Israel have waged against each other has escalated. Hassan Khodaei, a colonel belonging to the IRGC’s Unit 840 in charge of attacks outside of Iran was gunned down in downtown Tehran. Mysterious explosions have hit at least two secretive military sites, namely the Parchin base and an undeclared drone base near Tehran. There are speculations that small explosive-laden drones launched from within Iran may have been used in both of those attacks. An IRGC official also fell to his death, while an Iranian scientist tied to the Aerospace Industries Organisation (AIO) died of “food poisoning” and was subsequently declared a “martyr” – a descriptor not normally accorded to such mundane deaths.

Not all of those incidents may be tied to Israel, but panic is sometimes just as costly as the real thing. Amidst an increasing number of incidents, wild rumours started to circulate regarding even bolder Israeli plans, including one to assassinate Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Those were almost certainly unfounded, as doing so would be equivalent to a declaration of war.

The possibility that some of those rumours were also fuelled by Mr Taeb’s rivals should not be discounted. Mr Taeb made several powerful enemies who would not hesitate to pile up on existing difficulties. He may also have been angling to take on an even more senior position using his connection to the Iranian leadership. Indeed, Mr Taeb is known to be close to Mr Khamenei, who was his teacher during his early clerical years. He is also an ally of the supreme leader’s son Mojtaba, who has ambitions of his own. There may be a political dimension to his dismissal, as multiple candidates, including President Ebrahim Raisi and Mojtaba Khamenei, are widely believed to be trying to position themselves as Mr Khamenei’s successor.

This internal power struggle may have played a role in pushing Mr Taeb over the edge, but the spy chief was already on a slippery slope. Not only did he neither foresee nor thwart the series of suspected Israeli attacks that hit Iran, but he compounded this failure by being unable to retaliate. He failed to exact a price on Israel, despite bending the rules of engagement and widening the list of targets to include any Israeli who Iranian operatives could get their hands on.

Mr Taeb picked Turkey as the main hunting ground. Iranian intelligence operatives have a long history of operating in Istanbul, including by luring and kidnapping opponents. But the operation did not go as planned: Israel got wind of the plots and passed the information Turkey’s intelligence agency, MIT. As Iran expanded its list of targets, Israel responded by going public, issuing several dire travel warnings through regular channels, but also through direct public channels. The Israeli Foreign Minister himself publicly called on Israelis not to travel to Turkey. The goal was clear: As thousands of Israelis regularly stream to Turkey, the Israeli intelligence service couldn’t realistically protect each one of them. Instead, Israel chose to make as much noise as possible, to thwart the various Iranian plots that followed. This also made for a very public and embarrassing failure for Mr Taeb.

But Mr Taeb’s failure is more than the personal story of a powerful man falling out of grace. It is the latest in a series of missteps and setbacks that have gripped the IRGC since the assassination of Gen Qassem Suleimani in 2020. Israel is thought to have increased its operations in Tehran, from the killing of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a key Iranian nuclear scientist and IRGC member, in late 2020, to the spectacular assassination of the IRGC colonel in Tehran a few weeks ago. Suleimani’s replacement, Esmail Qaani, has lived in the shadow of his powerful predecessor, and failed to take on the same role as a de facto co-ordinator of Iran’s activities in the region. Suleimani had taken on a role greater than his position as the head of the IRGC Quds Force, often acting as Iran’s political and military representative abroad, and co-ordinating between the various Iranian allies. Two years later, the IRGC is being challenged at home, which may force deeper changes and may undermine Iran’s influence in the region.

This story isn’t over. Mr Taeb’s successor, Gen Mohammad Kazemi, is likely to try and show that he can be successful where his predecessor wasn’t. Prior to his appointment as the head of the Intelligence Organisation, Mr Kazemi was the head of the secretive Intelligence Protection Unit, whose role is to track down potential moles and leaks within the IRGC. It is unclear why Mr Kazemi didn’t take at least some of the blame for the recent failures, but his appointment makes it clear that his primary task will be to detect any internal issue. And once this is done, it is also evident that he will look to settle the score.