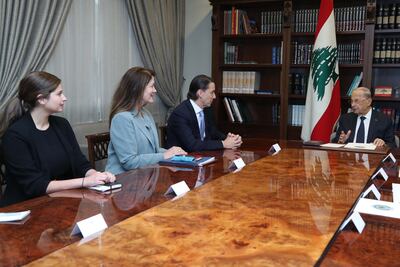

Last week, the Biden administration’s senior adviser for energy security, Amos Hochstein, arrived in Beirut to defuse rising tensions between Lebanon and Israel over their offshore gas fields. Israel had just brought a vessel to develop its Karish gas field, which it considers part of its exclusive economic zone, but the Lebanese responded that Karish was in a disputed area, requiring talks to delineate the maritime border.

While the technical aspects of the discussion are important, the Lebanese position had been fraught with contradiction, largely because Lebanon’s political leadership is competing over who controls the gas file. This represents the more important facet of what gas discoveries represent for the political class: a life raft for its political survival and domination, amid the worst economic crisis Lebanon has ever faced.

Aside from the openings it will create for corrupt practices – the cancer that has led to Lebanon’s economic collapse – the politicians see the gas as something else. If Lebanon can begin exploiting its reserves in the coming years, the pressure on them to engage in economic reform will dissipate. Two and a half years after the country’s breakdown, the political class has done nothing to reform the economy, showing little willingness to ever do so. The discovery of gas would push that imperative even further away.

At the same time, gas revenues will allow the political forces to engage in widespread clientelism, sustaining their authority. Hezbollah in particular would be able to secure regular funding, even though no politician or party will ever admit that it has its eyes on what should be a national resource. That would be a bold-faced lie, one similar to all the others major Lebanese political figures have made since the collapse of 2019.

In their mind, the political uses of gas revenues greatly surpass its potential economic or developmental benefits for an impoverished Lebanon’s population. That is why each side seeks to ensure that it eventually has greater access to the revenues.

The two major protagonists have been Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri and Gebran Bassil, the head of the Free Patriotic Movement and son in law of President Michel Aoun. Their disagreements, and who controls negotiations over gas exploitation, nearly undermined a unified Lebanese towards the gas reserves.

To secure control of the gas file, Mr Aoun, in whose shadow Mr Bassil operates, and Mr Berri have engaged in one-upmanship. Mr Aoun had declared that Lebanon’s rightful share of offshore gas fields is larger than what Lebanon has demanded, corresponding to an area encompassed by what is called line 29. The official position, included in a letter to the UN, is that Lebanon seeks a smaller area, within line 23.

Mr Aoun presented his maximalist bid as an effort to undermine Mr Berri, who had not made such a request. However, the President never formalised his demand by amending the letter to the UN to replace line 23 with line 29. Had he done so, Karish would have been a disputed field, forcing negotiations between Lebanon and Israel.

Mr Berri, realising that Mr Aoun was engaged in political manoeuvring to gain control of negotiations, responded in an indirect way. He instructed his representative on the military technical committee formed to negotiate with Israel, Gen Bassam Yassine, to underline that line 29 was indeed the correct line. This was a way of squeezing Mr Aoun into officialising the line 29 demand, which he never intended to carry out.

Recently, Lebanon’s position shifted after Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, made a speech effectively imposing unity among Lebanese leaders. After receiving Mr Hochstein, the Lebanese proposed, verbally, a modified line, one that would entirely encompass the Qana gas field, but leave Karish to Israel. The US envoy will now take this proposal to the Israelis, though diplomatic sources cited by Kuwait’s Al-Jarida stated that Mr Hochstein was unconvinced by it.

There are indeed many obstacles before a final deal with the Israelis is conceivable. However, the more pertinent question is whether the Lebanese people will ever gain from the country’s gas reserves. If a significant portion of the revenues goes to the political class and Hezbollah to sustain their system of hegemony and patronage, it is likely that the gas will do far more harm than good for Lebanon.

In many regards, Lebanon is no longer built on any identifiable social contract. It rests on a foundation of a post-war division of the spoils among members of the sectarian elite. Since the civil war ended, all major crises have revolved around which politicians would get what share of national wealth. The political forces, many of which rose during the war years, know only how to plunder, but appear to be thoroughly incapable of reforming the system, even if that is needed to preserve their cash cow of a state.

Lebanon’s gas is no different. One can see a looming disaster if the country ever begins to develop its offshore reserves. In the hands of a political class for which Lebanon’s greater interest is an alien concept, gas exploitation, frankly, may be better off failing.