With western leaders seeking to exert maximum economic pressure against Moscow for the war in Ukraine, it is logical that Russia's vast energy resources should become the primary target of their attempts to impose punitive measures.

Prior to the conflict, Russian sales of oil and natural gas accounted for around 40 per cent of the country's total budget, and the money earned from its global energy sales has helped President Vladimir Putin to invest heavily in building up the country's military strength. But now that the Kremlin has drawn on Russia's military prowess to go to war against neighbouring Ukraine, there is a deepening determination among western leaders to impose the most punitive measures possible.

With the Nato alliance wary of becoming involved in a direct military confrontation with Russia, which possesses the world's largest nuclear weapons arsenal, the West's search for other methods of punishing it have inevitably focused on its lucrative oil and gas sector.

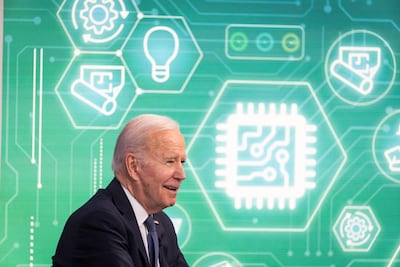

In this respect, the US administration under President Joe Biden has taken the lead by imposing a total ban on oil and other energy imports from Russia, including certain petroleum products, liquefied natural gas and coal. Companies will be given 45 days to wind down existing contracts for supplies. The order also bars new US investment in Russia's energy sector and blocks Americans from financing foreign companies that invest in the sector.

Washington isn't alone.

European leaders, too, are looking for ways to end their heavy reliance on Russian energy. The EU has announced plans to cut supplies by two thirds by the end of the year through a mixture of diversifying resources and building better storage facilities. In a dramatic turnaround from its previous policy of seeking to maintain a constructive relationship with Moscow, EU President Ursula von der Leyen warned it was essential for the continent to acquire new energy sources. "We must become independent from Russian oil, coal and gas," she said. "We simply cannot rely on a supplier who explicitly threatens us."

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has also announced that his country aims to phase out imports of Russian oil and oil products by the end of 2022, while active consideration will be given to banning gas supplies.

If the aim of these measures is to inflict maximum pain on the Russian economy, they have certainly achieved their goal. The rouble has halved in value since the start of the year, and there is now a genuine risk that Moscow will be forced to default on its debt repayments. To shore up foreign currency reserves, strict limits have been imposed on how much ordinary Russians can remove from their accounts.

Taken with the other drastic measures, such as freezing the $630 billion war chest Russia had stockpiled before the conflict, Moscow may well find itself struggling to pay for its war effort before long.

Meanwhile, as EU and Nato countries search for ways of making up the shortfall, the sanctions risk fuelling an energy crisis in the West.

Mr Biden conceded as much after signing the executive order, when he said that the reduction in imports would have a knock-on effect on petrol prices in the US, further increasing inflationary trends in the US economy. "This is a step that we're taking to inflict further pain on Putin," he added. "But there will be costs as well here in the United States."

In order to alleviate the pressure on supplies and prices in both the US and Europe, one obvious solution would be to encourage pro-western oil-producing countries, such as those in the Gulf region, to increase production. But even as a number of Gulf states have indicated a willingness to co-operate, Mr Biden's attempts to increase global supplies are now being hampered by Washington's broadly underwhelming Middle East policy under the current administration.

While both the UAE and Saudi Arabia are well-positioned to make up the West's current shortfall, they must co-ordinate their actions within the Opec alliance. Furthermore, Mr Biden has failed to cultivate relations with the two countries in a manner that could ease tensions between Washington and the Gulf that have been growing over concerns that the Biden administration is not taking security issues seriously relating to its long-standing allies in the region.

Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have been disappointed with Washington's policy towards Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen, especially following January's attacks on Abu Dhabi, in which three people were killed. The Biden administration, which took the Houthis off the US terrorist blacklist last year, has yet to put them back on the list despite those attacks.

There are also concerns that the White House may be willing to make too many concessions to Tehran as Mr Biden seeks to revive the controversial 2015 Iran nuclear deal. One consequence of its revival could be the ending of economic sanctions against Iran, which would help release funds that the regime in Tehran needs to bolster its destabilising activities in the Middle East.

If Washington is really serious about stabilising global oil supplies, then a good start would be to stop taking its key allies for granted.

The UAE has already proposed that the Opec+ alliance increase oil production at a faster pace than its current monthly target to ease volatility. In return, Washington needs to do more to reassure its allies in the Gulf that it takes their security concerns seriously, and acts accordingly.