Every year during Black History Month in the US, a televised interview with singer Harry Belafonte and actor Sidney Poitier from more than a half century ago comes to mind. Discussing the importance of black history, they note that its explicit teaching is necessary if the goal is to tell the full story of human history, as the contributions of African Americans – in science and medicine, literature and the arts, and so many other fields – have been deliberately ignored or distorted.

They add that contributions of African Americans are only part of what's missing. Also absent is an honest treatment of the dehumanising reality of slavery, the vicious legacy of segregation, lynchings, and the ethnic cleansing and systemic racism that have defined much of the African-American experience and that continue in different forms until today. Because the history that Americans have learned has been so whitewashed and shorn of the black experience, it is not only false, but also destructive and hurtful.

A personal example: when the Chevy Chase Land Company built our neighbourhood in north-west Washington a century ago, the entire area was "covenanted" white. This means that, by law, no homes could be sold to black families. As the neighbourhood grew, a need arose to build schools to accommodate the white families who had moved in. The land chosen for the elementary and high schools were areas that had been settled by freed black slaves who had lived there since before the Civil War – long before Chevy Chase's racist covenants. In an act that many would, with some justification, describe as ethnic cleansing, Chevy Chase secured a government order evicting hundreds of black families from their homes.

That such a thing happened in our neighbourhood, and the fact we learned about it only in the past decade, came as a shock. One of our children had gone to the resulting elementary school. For a decade, I had coached a baseball team that played on the adjacent field; we had been playing on stolen land and didn't know it.

The city council and the mayor didn't know this history either. There is a Washington Post story from 1931 – just two years after the evictions – that mentions new schools being built on the "rolling green hills", as if the land had been vacant, thereby erasing the evictions and demolitions.

There was a sense of shame and guilt within our community at this injustice, so we formed a group that was eventually able to get the story recognised, the name of the field changed to include the name of the black families who had lived there, and historical signage erected on the site telling the story of African-American dispossession. It was small but needed recompense.

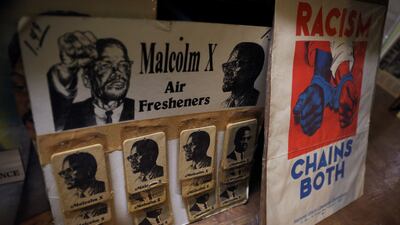

In this context, it's striking that during this year’s Black History Month, 15 state legislatures are moving to pass bills that would limit the teaching of black history. As an example, the legislation in Florida reads: "An individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, does not bear responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex. An individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race."

The bill is dead wrong. Americans need to know black history, about the African Americans whose contributions have been left out, and about the horrific pain they endured from the moment they set foot on these shores to the present day. Most importantly, Americans need to feel "discomfort, guilt, anguish and distress". We all need to feel it because we can never correct the sins of the past, unless we know them and then work to address their legacy.

Upon reflecting on this connection between history and guilt, one cannot help but think about the Palestinian people, many of whom had been expelled from their homes more than seven decades ago and had to live in refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan. I spent considerable time in these camps in the 1970s documenting stories of the Nakba. Palestinians narrated their stories, pointing to faded pictures of the homes they had left behind, and their fervent desire to return. One of them said: "The Jews say they remembered [about their lost homeland] after 2,000 years. For me, it's only been 23 years. How can they not understand that I want to go back to my home?"

During my journey back to the US, with these heartbreaking stories still fresh in my mind, I was approached by a former student. I asked her where she had been and she replied enthusiastically: "I just went home, my true home." I said: "But you're from Philadelphia, aren't you?" She acknowledged that was where she had been born, but a summer in Israel had helped her to discover her "true home".

In the years after 1948, Israel had seized the homes of those urban Palestinians who had fled, turning them over to new Jewish immigrants, and demolished 483 entire Palestinian villages that had been evacuated. The Jewish National Fund had planted forests on the sites of these villages in an effort to complete their erasure from history and memory. My young and euphoric former student had no knowledge of any of this, but I chose not to give her a history lesson or to make her feel "discomfort, guilt, anguish and distress". I did resolve, however, to make this my life's work.

Whether it's Americans who need to learn about what we did to Native Americans and African Americans; the British who need to understand the impact of their oppression of Ireland and the Indian subcontinent; the French who must make recompense for the horrors they inflicted on the Arabs of North Africa; or so many others – there are too numerous to list – we need to remember and teach our children a full human history, to feel discomfort and guilt for what was done to innocents, and find ways to end the legacy of the injustices that were perpetrated in our names.