The ties that run across the Herat River, which in one area forms a natural boundary between Iran and Afghanistan, tightly bind the people living on either side of it. There was a time when they were part of a single country. That era formally ended nearly two centuries ago, but it has survived informally through family links, a shared culture and a common language between eastern Iran and western Afghanistan.

This makes the protests that have taken place this week outside Iran’s consulate in the Afghan city of Herat deeply personal. "Where is your humanity?" read a sign held up by one man. He is one of thousands in a city left shocked, humiliated and outraged by a grisly crime suspected to have been perpetrated by Iranian border officers patrolling the river a fortnight ago.

Herat and its Iranian twin city Mashhad each sit over 800km away from Kabul and Tehran, their respective capitals. This is partly why few in the border region expect any actual results from a joint investigation announced today by the Afghan and Iranian governments.

The events began after nightfall on April 30, when a group of around 57 Afghan men and boys boarded a set of makeshift rafts – barrels, bound by ropes – and set out across the river, like hundreds of thousands of Afghans before them over the years, for better opportunities in Iran.

For some members of the group, including a 13-year-old boy, it was the first time. Others had made the journey many times before. Mohammed, Idris and Jalil, members of the same family, had previously worked in the Iranian construction sector. They returned to Afghanistan after losing their jobs earlier this year because of the coronavirus outbreak. But as Iran has taken steps to open its economy again, the three were asked by their former employers to make the illegal crossing and come back.

Almost as soon as they arrived, the group were arrested by Iranian border officers and taken to a guard post on a cliff overlooking the river. There, they allegedly spent the next 24 hours being stripped naked, insulted and beaten. If true, these actions amount to torture.

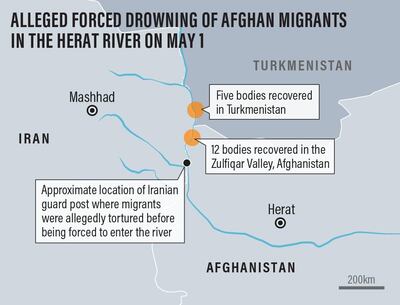

In the final hours of May 1, the group were loaded into vans and driven to the riverbank. According to survivors of what happened next, the guards fired rounds into the air and ordered the migrants into the water. The next day, a dozen bodies – including those of Mohammed, Idris and Jalil – were found nearly 20km away in Herat province’s Zulfiqar Valley. Another five turned up further downstream, in Turkmenistan. In total, 34 bodies have been recovered and some of them, say Afghan officials, bear signs of torture.

Although the Iranian-Afghan border is a place of intimate familiarity, it is also a place where modern events have bred deep distrust on both sides. Border patrol officers from both countries live dangerous lives.

The border is one of the world's most important drug trafficking routes. Afghanistan continues to produce more than 80 per cent of the world's illegal narcotics, and half of them transit through Iran. Afghan opium floods the Iranian market, where up to 5 per cent of the population is addicted, and then makes its way further afield, into Turkey, Europe and beyond.

Iranian police patrols have often found themselves outmatched by Afghan drug gangs crossing the 900km border equipped with armoured vehicles, night-vision gear and high explosives. In the four decades since the Iranian Revolution, around 4,000 Iranian officers have been killed fighting them. In fact, two of Iran’s most formidable military commanders – Qassem Suleimani, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps chief killed in a US strike in Baghdad in January, and his successor, Ismail Qaani – spent the formative years of their careers in the brutal drug wars of the Afghan frontier.

The problem has only been exacerbated by the fact that Afghanistan has spent the last four decades perpetually locked in its own deadly wars. In April alone, the Taliban carried out at least 11 attacks in the border provinces, of which 10 were in Herat. The militant group continues to rule over much of the region's countryside, though its grip has weakened over the last year. A series of strikes carried out by the Afghan Air Force from December to February killed a number of Taliban commanders, including the one responsible for Gulran District, where the Zulfiqar Valley lies.

In the 1980s, millions of Afghans made a run for the Iranian border. By the end of the 1990s, ten per cent of the Afghan population was living on the Iranian side. Half of them returned following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, but to this day tens of thousands of Afghans cross back and forth every month, most of them illegally. Many of them have been housed in refugee accommodation, had their children accepted to Iranian schools and received work opportunities.

Many others have received none of those things. Since the early 2000s, Afghan migrants have reported a “shoot first” culture among some of the Iranian border officers. The drownings that took place at the start of the month may be something new, but Afghan journalists in Herat have written about beatings and other forms of torture taking place at Iranian border posts for years. Darker still, since the start of Iran’s involvement in the Syrian civil war, untold numbers of male Afghan refugees have reportedly been forcibly sent to Damascus to serve as foot soldiers there.

Like many other messy borders flooded by migrants and refugees elsewhere in the world, the Herat River region has witnessed kindness and cruelty in equal measure.

This year, with the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic to the region, the tide of migration has reversed – with devastating consequences. In the first three months of the year, more than 250,000 Afghans were deported back across the river. Afghan authorities suspect that hundreds, if not thousands, of them were infected with coronavirus. Herat Regional Hospital, where the bodies of the drowned migrants were taken, is already buckling under the strain. Its doctors are hardened by the war to deal with things like triage and trauma care. But the hospital has no experience with a highly contagious respiratory disease. Last month, as the flow of deportees from Iran continued, more than 40 of the hospital’s staff found themselves infected in the space of a week.

All of this made it particularly galling when Abbas Mousavi, the Iranian foreign ministry spokesman, used a press briefing about the investigation yesterday to claim that Iran has provided the “best facilities” to its “Afghan guests” as part of its “good hospitality” shown to them since 1979. Combined with Tehran’s vehement denials that the forced drownings could have even taken place, Mr Mousavi’s lack of nuance or appreciation for the violence Afghans in Iran regularly face makes it doubtful that an impartial investigation is possible. Perhaps Iran and Afghanistan do not share a common language after all.

Since the day the first bodies were recovered from the Herat River, a video has circulated in Afghanistan showing the corpses lying in the sun amongst the reeds on the riverbank. It is a tragic scene. It brought to mind a particularly mournful verse by the poet Rumi, who was born in Afghanistan and has long been one of the great cultural unifiers for Afghans and Iranians.

“Listen to the complaints of the reed. It is telling us a tale of separation.”

Sulaiman Hakemy is deputy comment editor at The National