But I'm only human after all/I'm only human after all, don't put your blame on me.

These are lyrics from the song Human by Rag'n'Bone Man. He’s but one in a long line of musicians, writers and philosophers to wax lyrical about the strangely appealing contradictions and perfect imperfections that make us humans who we are.

With ChatGPT, we are starting to hear the machines’ last laugh at our imperfections: our spelling mistakes, the hours, days and weeks we take for research, the off-days that may inspire the necessary creative spark.

And yet here we are: we have created these machines to airbrush the very things that make us human out of our daily life.

We have spent the best part of 20 years creating algorithms, teaching computers to do what we do and how we do it. Granted, many of the tasks that the automata will take on are the “jobs that suck”, as a colleague in futurist studies recently argued – those mindless, repetitive, unpleasant and heavy jobs.

Recent advances clearly take on some of the skill that goes into content creation of various kinds: design, investment, animation, research, writing columns (not this one), even writing code, and, I’m sure, a host of illegal and nefarious activities.

Whether or not you feel that these AI tools are innovative – helpful or not – the direction of travel is clear: more and deeper automation.

So this is the time to examine what will happen to us – and whether now is also the time to elevate our individual and collective worth.

Why now?

It’s not just about the AI developments. It’s also because our lives are inextricably linked to digital realities and to pressures on our species due to the worsening climate and ageing populations (in several places).

Lucy, one of the first upright hominids, lived in Ethiopia about 3 million years ago – 1 million years after walking on two feet became a thing. It has taken another 3 million years or so before major traits associated with a complex brain, such as language, started appearing. Our current model of humans – Homo sapiens – appeared about 300,000 years ago.

All this is to say that it has taken hundreds of thousands of years to evolve into who we are. Socially and from a health perspective, we have been aided by technology, critical to our survival, and this has begun with the emergence of tools and fire. It has taken 1.7 million years to go from the most primitive tools – axes and sharp stone flakes – to the first Industrial Revolution in 1750, when automation and industrialisation began. The 250 years since has ushered in a further three industrial revolutions that have ultimately propelled us into the embrace of artificial intelligence.

There’s no stopping us.

But, from an evolutionary standpoint, we are still the same cave-folk as we were 300,000 years ago: our brains and physiques have essentially stayed the same. What’s going on? Are we capable of dealing with this tech-acceleration and make sense of it? What will the future hold?

I have heard numerous speakers, technologists, investors and others suggest that we need to embrace this inevitable trajectory: children as young as two are capable of placing an order from an iPad (what need might they have for placing an order? Never mind).

While courses about AI are popping up in elementary schools, I wonder, is that what we want?

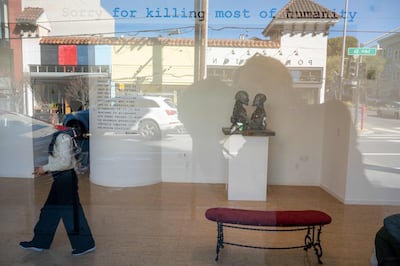

It is so seamless and easy to adopt and adapt to the next technology that makes our life easier, integrated and seamless. Increasingly our imperfect selves are hidden from view whether through a social media filter or through the use of AI assistance that masks our efforts or shortcomings.

Over time, we might lament the loss of identity, culture and diversity: we’ll all speak Globish, that simplified, somewhat bland and almost universally accessible version of English that may become the language of choice for a humanity that’s a sidekick to AI.

I suggest that the next frontier is simply this: being human.

As we accelerate towards a general AI, we must think about how we demonstrate the value we bring as humans. We might let the machines do the work, but decide to resort to writing books by hand, reclaim our existence away from online personas and avatars, insist on our singular identity – whichever way we define it.

After all, we are Homo sapiens aided by technology; life is not about the technology that is created by humans. It comes down to having to decide on one of the fundamental tensions we have identified in our recent “Global 50 Opportunities” report: whether technology is our master or whether it is a multiplier of prospects to achieve prosperity.

Our challenge is to not lose ourselves in technology and instead emerge as a stronger and more evolved species that celebrates its achievements, demonstrates its values and is clear about the direction of travel for the coming 300,000 years. We’re only human after all. But that is not an excuse to make a very human mistake and let algorithms define us.