Live updates: Follow the latest news on the UK general election

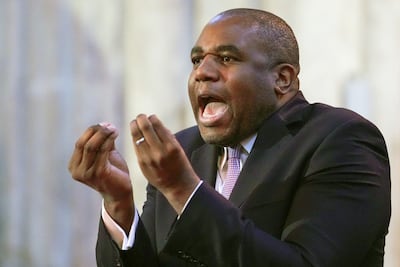

As he hopes to shed the colonial hangovers of the UK's diplomatic service, David Lammy could also become the first foreign secretary to accept the UK's position as a “middle-sized power” in a shifting world order.

Mr Lammy, a lawyer-turned politician who has served as MP for London’s Tottenham since 2000, has been Labour's top diplomat through the invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza war. With the party consistently leading the polls by 20 per cent, he is expected to be appointed foreign secretary after the general election on July 4.

He has spent the past months meeting with possible counterparts in the US, France, Ukraine and the Middle East, while forging a foreign policy in line with the party’s domestic ambitions and his personal heritage.

He has led the party’s shift in position towards Israel, from unequivocal support for Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, to a more critical one. He has called for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire, and questioned the UK's arms sales to Israel without yet calling for an end to these.

His foreign policy vision, which he calls “progressive realism”, would continue British support for Ukraine, strengthen multilateral institutions such as Nato, engage the UK's Gulf allies in a regional peace process, and also work with China on a green transition.

Born in London to Guyanese parents, he continually reminds audiences that his family’s heritage as slaves to the West Indies will be part of his “responsibility” in a future Labour government – bringing reforms to a Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office that is often criticised as elitist.

"Growing up in Tottenham, in Thatcher's Britain, I knew what it meant to go to bed hungry, to be told to limit my ambitions," he said in a recent campaign video.

His parents gave him a powerful sense of Guyanese traditions, and yet he always had questions about his ancestors. “The truth is, we are the descendants of enslaved people and that means that there's always a bit of you that doesn't know where you are from,” he told The National in an earlier interview in Dubai last year.

A DNA test that he took in 2007 helped trace his family’s origins to southern and West Africa, he added.

He fears the need for a sense of belonging in British society is fuelling tribalism and identity politics at the expense of unity. “We're living in a society where there are profound problems with a new tribalism that's driving us apart, not driving us together,” he said then.

This is a subject he explores in his book, Tribes: a Search for Belonging in a Divided Society (2020).

Inheriting a middle-sized world power

Mr Lammy would be taking on the role at a time when the UK's influence on the world stage has declined, experts say. This is caused in part by the cuts to the foreign aid budget, and the growing sway of emerging economies from the so-called Global South.

Veteran diplomats Tom Fletcher, Moazzam Aziz and Mark Sedwill described the UK as an “offshore middle-sized power” in a landmark foreign policy report, The World in 2040, published by the University College London’s Global Governance Institute earlier this year.

Lynchpin vs middle power

“It's not the 1990s any more, where you had key linchpin states really underwritten by the US, who had the power, authority and who were able to drive forward collective action,” said Dr Tom Pegram, a co-author of the report and associate professor of Global Governance the UCL.

Instead the UK would need to work to develop coalitions with other middle powers, with whom it may not always share the same values, to achieve its overseas objectives.

“If the 1990s were the years of the G7, today the G20 is a much more representative body of states,” Dr Pegram said.

“It's a question of distinguishing between strategy and tactics. There are countries out there that are incredibly important now within the geopolitical theatre, who don't share our values and we need to get them on side.”

This is a reality that Mr Lammy appears to accept. In an essay for Foreign Affairs magazine, which served as the blueprint for his progressive realism foreign policy, he called for a mastering of the “art of grand strategy” in British diplomacy.

This would take cues from the “WhatsApp diplomacy” of Emmanuel Macron, whom he says pursues more practical economic relations overseas, but also of emerging actors including India, Brazil and the UAE whose “dynamic diplomacy” sees them pivoting away from the US and striking deals with all of the world's great powers.

Although the UK must acknowledge China’s aggressive posturing and threatened invasion of Taiwan, it was also bound to working with China on tackling global issues like climate change, he suggested.

More diplomats were needed on the ground, and fewer of them in Whitehall where they sit at their desks compiling biographies, he said, promising to establish a new “school of diplomacy” that would revamp the ossified practices of the FCDO.

“It’s an acknowledgement that the UK is a middle power, a diminished country on the world stage and has been so for some time, both in terms of moral standing and economic offerings,” said Dr Judith Jacob, director of geopolitical risk and security intelligence at the consultancy Forward Global.

“We’re not investing heavily abroad and we’re not a great investment destination either. Other countries look at our political squabbling and think – what's going on there?” she added.

Restoring stature

Labour leader Keir Starmer has promised to spend 2.5 per cent of GDP on defence and to maintain the continuous at sea nuclear deterrent. Among the party's candidates are army veterans, former intelligence offices, and diplomats.

Balfour Project

One challenge for Mr Lammy will be maintaining relations with the US should Trump be elected president this year, with a US-UK trade deal still being negotiated. He is a friend of Barack Obama's, and the Labour party's policies are often aligned and shaped by those of Biden's Democrats.

At a Republican party event he vowed to find “common cause” with a possible Trump government, and has already met with former secretary of state Mike Pompeo.

But this could be undermined by earlier comments he made about the then-president, and the continued pronouncements against him by members of his party. His more vocal past under Labour's Jeremy Corbyn-led leadership will have to be tempered, experts say.

Mr Lammy turns to France in his ambitions to build an EU-UK security pact, where he is said to have built good relations with Mr Macron and his entourage.

During a visit to Ukraine in May with shadow defence secretary John Healey, he stressed Labour’s continued commitment.

Yet Mr Lammy’s vision is also soft on numbers. He has declined to say whether he would increase foreign aid budgets back to their pre-Covid levels of 2.7 per cent of GDP, or whether he would increase the UK's support for Ukraine.

“It’s an exercise in expectations management,” said Dr Jacob. Decisions on Ukraine are still likely to be guided by the US, and the outcome of the presidential elections there later this year, she added.

Whereas Boris Johnson was caught reciting Rudyard Kipling during a visit to Myanmar when he was foreign secretary, Mr Lammy’s approach is more likely to be in tune with the mood in the Global South, which makes up more than half of the G20.

“Lammy recognises our standing among countries of the Global South, given Britain’s colonial history. He does acknowledge that our standing as a superpower has been whittled down,” said Dr Jacob.

“I suspect he might do a better job at restoring stature.”

Labour's Gaza tone

Mr Lammy has been actively meeting with Arab ministers, making more than a dozen trips to the region since the war broke out after the October 7 Hamas attacks.

The Gulf is where he sees the brokers of a potential peace process, prompting trips to Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

He has said he would accept the verdicts from the international courts, where Israel is currently being challenged by South Africa at the International Court of Justice, and a request for arrest warrants was made by the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Where Gaza is concerned in the UK, Mr Lammy appears to be meeting everyone – from Arab ambassadors, to former British diplomats to the region and international rights groups.

His willingness to engage personally has won him praise – though one campaigner expressed surprise at the inexperience in some of his questions.

But critics say this is not enough. They call for more sanctions on Israeli officials, an end to UK arms sales to Israel, and end to the UKs trade agreement with Israel.

Labour has sought to fix the damage to the party among left-wing and British Muslim voters, who have felt alienated by its stance on Gaza. The election has seen a wave of challengers to Labour, most of them former members or supporters of the party, running with Palestine as their main cause.

Palestinian statehood recognition features in the Labour manifesto unveiled last week as “part of a peace process”.

This leaves it open as to whether a future Labour government would unilaterally recognise Palestine without agreement from Israel – something which current Foreign Secretary David Cameron had promised to deliver.

The vacuum over a UK policy on Palestine has prompted a group of former British diplomats to draft an action plan for a prospective UK government.

“Labour has a chance to make a break from the Conservatives and show that it stands for a values and rule-of-law based government,” Andrew Whitley, chairman of the trustees of the Balfour Project, which published the action plan, told The National.

Statehood recognition would be a low-hanging fruit. “UK really needs to act swiftly to join other European countries in recognising Palestine. This is not something to be deferred to some indefinite peace process, or to a better time,” he said.

“This is the moment where it really needs to happen, that Britain has a chance to show politically, that it accepts its responsibility.”

The UK could leverage its strong security relations with Jordan and Israel, as well as its “important” economic relations with the Gulf states, in bringing about a peace process and accountability for the Palestinians.

“It’s the time to use that influence that they have, rather than simply waiting to see what’s coming from Washington,” Mr Whitley said.