February 25, 1984: Five military aircraft swoop low over marshland, with several turning hard, possibly after firing weapons.

Below them, the wake of a speed boat heads east through a passage in the dense reeds.

It's ten days into Operation Kheibar, Iran's military operation that saw motor boats carry troops through vast marshland at the height of the Iran-Iraq war. Iraq thought the marshland would be impassable, until the Iranians caught them off guard.

Other pictures show large numbers of boats speeding through the wetland, in declassified US spy satellite imagery that shows the granular detail available to US intelligence after 1971. That year, new satellites known as KH-9 Hexagons became operational, which provided unprecedented photographic clarity.

The imagery has been declassified, with samples available for the public by the US Geological Survey in chunks of tens of thousands of images since 2013. Since the images cover such vast areas – there are 900,000 in total – researchers are still finding use for these incredible historical records.

Small moments with huge implications are pictured, like the beginnings of an Israeli settlement in Netzarim, Gaza, pictured in 1974, temporary-looking structures built, according to UN documents, on the land of the Abu Madyan tribe.

Today, the area has been turned into an Israeli-controlled buffer zone, cutting Gaza in half.

Two years later, declassified US State Department cables fretted about expanding settlements from Gaza to the Sinai in Egypt, including tent camps. It's not clear if this satellite imagery was used to monitor this expansion.

Other images are equally revealing, after The National spent many hours trawling through the photographs, which cover thousands of square kilometres.

Watching the ceasefire

May 1974: US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was in talks with Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat in the wake of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. Egypt regained the Sinai, lost to Israel in 1967, in its surprise attack, but its forces were eventually routed there.

In Syria, after a colossal tank battle for the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, Sadat urged Kissinger to push the Israelis back from occupying even more of the country, to get them out of the town of Quneitra.

Kissinger complained bitterly about negotiations with the Israelis, staring for hours at maps and, according to apparent Israeli leaks of the talks, arguing over several hundred metres of land "like a rug merchant".

Behind the scenes, the K-9 satellites could monitor everything. Military positions across the Golan, like the bunker complex pictured below, could be tracked at high levels of detail.

The Hexagon image below is dated June 25, 1974, showing the Quneitra valley, where Israeli and Syrian forces fought fierce battles in 1973 and clashed around 1,000 times in the following year.

The following day, a compromise would be implemented, with Israel pulling back from a 25-square-kilometre area.

Yet the image shows palls of smoke in the valley. It’s not clear if this is from farming activity or last-minute fighting before the deal.

Working that out would be the job of analysts at the US National Reconnaissance Office who would spend countless hours studying the vast images, nearly 600 kilometre swathes of land at a time.

“Photograph interpreters were specially trained people. They would elicit from what we might consider a grainy picture critical information through mensuration techniques and other skills. You could look at the same picture and say, ‘well, it looks like a fuzzy thing,’” says Charles Duelfer, former special adviser to the director of the CIA on the status of Iraq’s suspected weapons of mass destruction after the 2003 invasion.

Before then, he worked as the acting chairman of UNSCOM, which oversaw inspection of Iraq's WMD facilities.

The capability was invaluable: not only could the US spot the movement of Soviet weapons – especially nuclear – but it could provide allies with vital information about their enemies, such as troop movements.

This also applied to countries that had mixed relations with the US, like Iraq under Saddam Hussein, which was also strongly backed by the Soviets. America supplied imagery-derived information about Iran’s forces, while the Soviets and others supplied arms and the KGB cracked Iranian communication codes.

“There is a diplomatic currency, which is intelligence sharing and overhead imagery, or imagery derived intelligence, was a very valuable thing, much more so than before commercial satellite imagery became available. The degree of sharing was always case by case. It became a form of art, to show imagery that was often very sensitive,” Mr Duelfer says.

“I was in the State Department's political military affairs bureau from 1982, overhead imagery was an important tool for us. It gave clarity to other sources of reporting on ground movements. The way the imagery bureaucracy worked in those days, the State Department channelled imagery intelligence through INR (the Bureau of Intelligence and Research) where a couple specialists were part of the inter-agency committee that prioritised tasking.

"Overhead imagery was a far more important and unique tool then than it is now, because today everybody and their dog is an imagery analyst and there’s lots of imagery available to everyone. If you go to Bellingcat, they've got some really smart analysts and they're doing amazing things.”

Mr Duelfer, who went on to serve as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for arms control, describes the importance of the US provision of satellite intelligence to Iraq during its bloody eight-year war with Iran. Hexagon imagery from the period shows thousands of kilometres of trench lines and defensive positions appearing like a First World War battlefield.

Iranian positions are clearly visible: no dug-in armoured vehicle or gun could be hidden in ambush, evidenced in this image of defensive horse shoe-shaped earth berms seen around Ahvaz, Iran.

These sites could be observed by Iraqi aircraft, if it wasn’t for the fact that Iraq’s air force struggled in the early years of the war, particularly after a devastating Iranian strike on one of its main airbases, H-3, allegedly after Israel passed intelligence about the base passed to the Iranians.

Iranian airbases, too, were clearly observed, with fighter jets pictured here by the side of a runway in Tabriz, their sleek lines suggesting they could be US-made F-5’s captured during the 1979 revolution and used in the H-3 operation.

“Air supremacy was an issue in the Iran-Iraq War, so this was important. And the ability for Iraq to know if there's an Iranian troop mass, you know, 15 kilometres back in such and such a place, that's extremely important," Mr Duelfer says.

"We would provide information to the Iraqis on Iranian troop disposition, and the Iraqis could use that for targeting weapons, including potentially chemical weapons. Iraq used chemical munitions to help counter the Iranian tactic of using 'human waves' to assault Iraqi positions.

"This Iranian tactic was effective, so long as you didn’t care about casualties. The natural antidote to human wave assaults for Iraq was chemical munitions.”

One Iraqi general described after the war how "American intelligence provided us with information before Fao (a major offensive). The Iraqi intelligence service brought a US government representative, who provided satellite pictures, to meet us".

Mr Duelfer continues: “We had a policy where we were providing intelligence, because there was the policy to tilt towards Iraq. We did not want to see Iraq lose. It’s important to recall that the chemical weapons treaty didn't exist at the time, it was under negotiation.”

Every aspect of the conflict could be seen, from devastating air strikes on oil infrastructure in Abadan – retaliation for Iranian bombing of refineries in Baghdad, to Abadan’s street by street detail as the two foes clashed in the city.

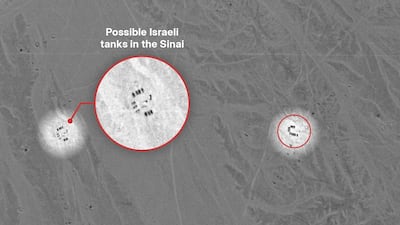

Further detail in the collections can be seen in the two pictures below, dated October 14, 1973, during Egypt’s counterattack in the Sinai. Groups of armoured vehicles, likely Israeli due to their location far back from the Egyptian attack that day, can be seen positioned in the desert far from a main road.

Zooming out, it's possible to map out the positions of entire brigades – an entire conflict observed from space, for the first time.

Former intelligence analysts, speaking to The National on background, highlighted some of the limitations of the imagery when viewed without context, such as "Sigint" or intercepted enemy communications. They also highlighted the lack of "persistent" observation due to the time it took to obtain the photographs.

"Hexagon was wet film with required recovery and processing, so time from image to use was measured in days. That is OK for strategic intelligence but terrible for fast-moving crises. That’s one reason why we flew U-2s spy planes over Cuba during the missile crisis," one analyst said, referring to high altitude spy planes.

In terms of strategic intelligence, an image from 1980 shows the huge Soviet military build-up in Afghanistan at Kabul International Airport following the USSR's invasion, with analysts able to count the number of helicopters, vehicles and cargo planes – and warn allies in the Afghan Mujahideen.

"Patterns of life are critical," said another analyst, who worked US military intelligence for decades, describing a common method of analysing a target.

"Having a ‘long stare’ at a country’s military gives the analysts a chance to ‘cheat’ as they know where the units deploy from and deploy to. Understanding the doctrinal employment of the targeted country’s armed forces is also key," he says.

The US and allies devoted significant time to understanding how the Soviets organised their forces, approaches often passed on to their allies, including Iraqis, Syrians and Egyptians.

"Imagery analysis is done in conjunction with using all the disciplines of intelligence to hone the analyst in. For example, if you had SIGINT indications of a given type of radar or a certain type of transmission it could be associated with a platform," the analyst adds, referring to a specific type of weapon, aircraft or radar.

"That platform is often associated with other platforms or units. Certain mobile surface to air missiles, for example, in Soviet doctrine (and thus the nations that bought their equipment and thus get their manuals) are used to cover artillery, HQ units, and reserves. Find one thing and start to search outward and you often find others. The game of signatures across spectrums is timeless, and ever a contest, but the fundamentals are the same."