Areej Fadhil wanted her wedding to be a memorable celebration of love and history.

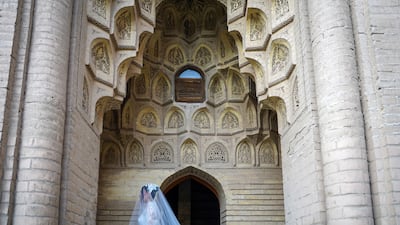

Ms Fadhil and her husband exchanged vows this month at the 12th-century Abbasid Palace in Baghdad, becoming the first couple to hold a wedding ceremony at the historic site.

The decision by authorities to open up heritage sites for parties has ignited a fiery debate across Iraq.

While some view it as an opportunity to showcase the nation's rich history and culture, others fear it may lead to irreversible damage to sites that have endured decades of conflict, neglect and looting.

“It is part of our marketing strategy for such sites,” Ahmed Al Elaiyaie, spokesman for the Iraqi Culture Ministry, told The National.

Approvals are given with restrictions to protect the sites, he said.

“Since I was a little girl, I dreamt of having a luxurious and unprecedented wedding party in Iraq,” Ms Fadhil, 30, told The National.

She was inspired by the wedding parties that are held at heritage and archaeology sites in other countries.

“These parties are like a dream come true for couples,” she said.

After a visit to the Abbasid Palace, she picked it as the venue for her wedding and immediately contacted an event management company.

“I was fascinated by the palace,” she said. "I had read a lot about it."

The couple delayed the wedding for months until they received the approval in February.

Still, the use of the heritage site came with some permutations.

No nails could be used in decorations, the number of guests could not exceed 50 and a traditional music band would have to be hired.

The couple also had to use items linked to Iraqi heritage, such as copper ware and plants like the camomile flower, which Assyrians considered the gift of the earth.

“Everything was mesmerising on that night,” she said. “I felt like a surreal experience, my whole body trembling with excitement,” she added.

Silent witness

Nestled in the heart of Baghdad, Abbasid Palace stands as a silent witness to centuries of history, its ancient walls whispering tales of dynasties and conquests.

Once the opulent seat of power of the Abbasid Caliphate, the palace now serves as a poignant reminder of Iraq's rich cultural heritage.

Baghdad – also known as the Round City and the City of Peace – was built by the Abbasid caliph Abu Jaafar Al Mansur between 762AD and 775AD to serve as the capital of the Abbasid Empire that stretched from present-day Algeria to Pakistan.

For the 500-odd years of the Islamic Golden Age, the city was a hub of economics and politics, attracting students, poets, scientists and merchants from all over the world.

The era ended with the Mongol invasion of 1258AD.

Overlooking Tigris River, the Abbasid Palace is one of few remaining sites from the Abbasid-era in Baghdad.

It is believed that it was built by the Caliph AL Nasser Le Deen Allah.

The two-storey building has distinctive Islamic architectural patterns from later Arab styles.

The rectangular complex is built around a courtyard and is heavily decorated with geometric and floral shapes, as well as calligraphies.

"Have the ruins of Iraq become venues for wedding receptions?" asked Baghdad resident Mohammed Ali, 49. "This site is not even open to the public. How did they allow such a noisy party?"

Iraq has almost 25,000 archaeological sites. They have all been badly affected by decades of war, lack of security and general mismanagement.

For decades, many of these sites were left to decay. Although they were closed to the public, they were poorly guarded and were an easy target for looters.

But in recent years, authorities started to open these sites to the public and have allowed some events to be held, such as photo sessions.

“Using archaeological sites under tight restrictions is allowed in many countries,” Mr Al Elaiyaie said, affirming that the wedding party caused no damage to the site.

Another Baghdad resident Salawa Hassan disagreed.

"Marketing such sites must come through public and official routes, not through private parties that damage the site," Ms Hassan said.