In the early days of the war in Gaza after the October 7 attacks, Prof Lawrence Freedman declared that one sure thing was Israel was no longer interested in restoring any deterrence it held over Hamas but instead was intent on ensuring it could never stage a repeat.

The King's College expert and author of the book Deterrence said the same could not be said of other opponents of Israel.

“We could ask whether deterrence was ever really the policy with Hamas, but it certainly is not now. Israel has no interest in persuading Hamas not to attack again,” he wrote on his Substack account.

“It wants to make sure that it can never do so again. But it does need to deter Hezbollah, and in practice, Iran.”

About seven months on, Aaron David Miller, a former Middle East analyst at the US State Department, believed the events of October 7, coupled with Iran’s missile and drone barrage on April 14, have ushered in a new era for the region.

“The entire Israeli conception of deterrence, you could argue, collapsed on October 7, and then April 13/14,” Mr Miller told The National. “The threat can't be over because a new reality has been created.”

Deterrence

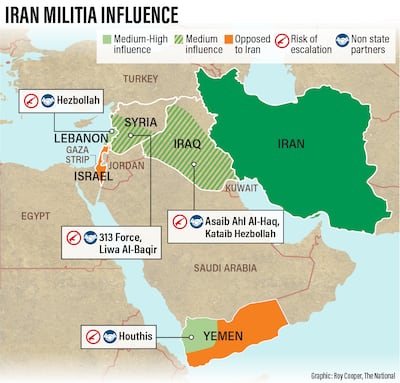

Prof Freedman noted Israel had not only focused on Hamas but had quickly engaged with Hezbollah targets in Lebanon and, within weeks, Houthi threats from Yemen became real.

In real time, what Prof Freedman in 2004 defined as deterrence – setting boundaries for aggressors and establishing the risks of crossing those lines – has played out.

Israel and Iran settling into a new era, with the prospect of direct attacks, remains very much a possibility. Israel has been bolstered by the loose coalition of countries that came to its defence in mid-April to help to shoot down nearly all of Iran's projectiles.

Iran has shown its ballistic arsenal can hit Israel on the ground.

“There was no precedent for what happened on April 13 and 14,” Mr Miller said. “Never before has Israel – in any active combat situation – had support from the US, the Brits, the French, the Jordanians publicly and at least three Arab states.”

A regional source close to Iranian-backed militant groups told The National that after Tehran's decision to launch drones and missiles, Israel had suffered a long-term blow to its vow to provide a safe haven for its citizens.

“The existing balance of deterrence in the region has not fallen but is being reformulated,” he said. “The important thing is that the Iranians have re-established the balance, albeit temporarily, waiting for the new equations of engagement to crystallise.”

Some in the Iranian camp are strengthened in the belief the Israelis “will not dare to attack Iran's security directly”.

In Washington, there is a sense that the immediate crisis has been averted but how long the relative calm will last is anybody's guess. Meanwhile, Mr Miller is adamant about one thing.

“There is no prospect of it being over,” he said. “There is no crisis-amelioration mechanism that they have directly or by a third party.”

Chuck Freilich, a former Israeli deputy national security adviser, said to fully deter Iran going forward, Israel would need the US to step up and give the regime “a hard slap, harder than Israel just gave” in its drone attack in response to what was launched on April 13.

He said Israel was in a strategic bind for now, however, because Prime Minister Netanyahu had failed at building strong international support, not just on the Iran front.

Retaliation

In the lead up to Iran’s telegraphed April 13 attack, the US actively courted allies, helped to organise a united response and then urged Israel to use restraint in their retaliation.

“I think the administration did an effective job at preventing these tensions from boiling over,” Ali Vaez, director of the Iran project at non-governmental organisation the International Crisis Group, told The National.

But he added that the administration of US President Joe Biden had let previous Israeli attacks on Iranian targets go unchecked, which likely emboldened them to take action on the Iranian embassy compound in Damascus on April 1 – the trigger for Iran's missile and drone assault.

“The fact that the Biden administration failed to establish certain red lines with Israel was also, I think, primarily the result of what led Israel to push the envelope too far [in Damascus],” he said.

Mr Vaez argued that the next round of “tit for tat” between Israel and Iran could be “even more dangerous because they have started to rewrite the rules of the game”.

In the Iranian camp, confidence in their own deterrence against Israel has also not precluded warnings of a new round of hostilities when the dust has settled.

“Israel may try to choose a different time and place, in which Israeli fingerprints will not be exposed,” the militia source said.

Matthew Levitt, director of the Reinhard programme at the Washington Institute think tank, said Israel's actions against a drone base in Isfahan were driven by its desire to restore a deterrent effect, especially as it defied US advice to “take the win” of blocking the Iranian assault.

“For that, they don’t necessarily need US engagement – Israel famously argues that it never asks others to fight its wars,” he said.

“That said, Hezbollah and others have grown strong, to varying degrees, due to a policy of kicking the can down the road.

“It remains to be seen if Israel will be willing to keep kicking that can or if, as several Israeli officials have said, they will no longer live with a gun to head, not from the south and not from the north.”

Escalation

Prof Freedman has noted that the academic theory of conflicts automatically worsening does not often bear out. That fear has certainly defined much of the commentary around the cross-border spread of tension beyond Palestine-Israel.

“Escalation is used regularly in connection with any type of conflict to show how it might move to a new and potentially more dangerous and violent level and become much harder to contain and resolve,” he has said. “Escalators can go down, as well as up.

“More seriously, the metaphor bore little relation to the actual conduct of wars. They rarely unfold in a linear fashion, moving from one step to the next.”

Bertrand Badie, a leading Middle East expert and professor emeritus at Sciences Po University in Paris, said outside powers would have less sway to contain escalation than the choices made by the leadership on both sides.

“My conception of international relations is that the choice in the last instance is always that of the decision-maker and not that of pseudo geopolitics,” he told The National.

“The decision-maker interprets the situations and chooses either offensive strategies, delaying strategies or return to peace strategies.

“I have the feeling that in Israeli political culture there is no plan B,” he added. “When you play power politics and your invulnerability, considered absolute, is thwarted by attacks like those of October 7, you are forced to subscribe to the escalation of power. You have no other way out.”

Prof Badie added that “structural uncertainty” existed over whether Israel wanted deterrence or to seek advantage in pursuit of victory across the board.

“If October 7 can allow Israel to neutralise Hamas, neutralise Hezbollah and neutralise Iran, then it will be considered a major strategic event. I personally think it’s impossible because it opens the perspective of never-ending escalation.”

For now, a full-scale reckoning is seen as the less likely option.

“Iran’s response to Israel’s presumed retaliatory strikes has been muted, signalling intent to avoid a further escalation; still, the Israel-Iran shadow war will continue over the coming weeks and sporadic escalatory episodes remain likely,” according to a client note from Control Risks' Victor Tricaud.

“Accordingly, regional states within Iran’s sphere of influence will continue to face threats. As part of continued efforts to roll back Iran’s regional influence, key Israeli targets will include infrastructure used by Iranian forces and Iran-backed groups, particularly in Syria and Lebanon.”

The Iran camp can tell its own side that Israel was embarrassed on April 13 but did not up the ante in response.

“The scene in the skies of Israel on the night of April 13 will not be erased from the memory of the Israelis,” the source said.

“The evidence for this is the mysterious Isfahan operation, which according to some Israeli estimates seemed weak and did not match the Iranian response.”

That view on the ground tallies with the perspective of US-based analysts sympathetic to Iran.

“I think this chapter is closed,” Mr Vaez said. “But the next one might open very soon.”

Nuclear overtones

James Heappey, a former soldier who stepped down last month as the UK's armed forces minister, has said the reason for so much debate around deterrence was that the Cold War had provided certainties that no longer could be relied on.

“I think the understanding between the Soviets and the West over the sort of way that nuclear escalation, for example, would be managed was increasingly well understood,” he told the BBC.

“The reality is now there are actors in the world that are irrational and we don't understand to the same extent. I think that makes this a very dangerous time indeed.”

In regional terms the new reality needs to settle in and Mr Vaez cautioned that recent events could push Iran towards nuclear capabilities.

“There is a dilemma that I think it's important for us to take into consideration and that is the fact that the more Israel succeeds in diminishing Iran's regional deterrence and highlighting Iran's vulnerability from the perspective of conventional military capabilities, both offensive or defensive, the more [Israel] failed by pushing Iran towards the alternative available to Iran right now, which is nuclear weapons.”

Whatever happens, Prof Badie is unlikely to alter his view that all this should be seen through the prism of regional power dynamics.

“Israel has had a security culture since its creation, which is entirely based on the game of power, that is to say, a bet of its invulnerability,” he added.

“Israel has done everything from acquiring nuclear weapons with programmes that began at the end of the 1950s to various campaigns carried out recently to contain the risks to its security by escalating its power.”