Animal testing remains widespread, but the long history of campaigning against it has made some inroads, with some sectors pioneering alternative methods and scientists highlighting its shortcomings.

A significant number of animals continue to be used for testing, with Humane Society International saying that more than 115 million are used in labs around the world each year.

The pharmaceutical sector tops the list of users, with companies including Pfizer claiming that animals "provide important insights into how a disease works within the body", which can help efforts to discover and develop drugs.

Dr Jamila Louahed, global head of research and development for therapeutic vaccines at pharmaceutical company GSK said animal testing was crucial for clinical trials. "We don’t do it for fun," said Dr Louahed, who is also head of research and development at the company's site at Rixensart in Belgium. "We do it to generate the right data."

Big fight

Next year will mark 150 years since the National Anti-Vivisection Society was founded in London to campaign against the cruelty inflicted on animals in the name of science. Dr Alan Bates, in his book Anti-Vivisection and the Profession of Medicine in Britain: A Social History, said campaigners "raised petitions with hundreds of thousands of signatures, more than for any other cause of the time".

Animals are subjected to a wide variety of procedures, including force-feeding of chemicals for toxicity testing, exposure to infectious diseases and infliction of wounds or burns to study healing, Humane Society International said.

Cruelty Free International said animals that do not die as a result of procedures are routinely killed afterwards.

Mice accounted for the majority of animals used in testing, but the group said more than 200,000 dogs and more than 150,000 non-human primates were used in 2015. It added that the number of animals used for science globally hit 192.1 million that year.

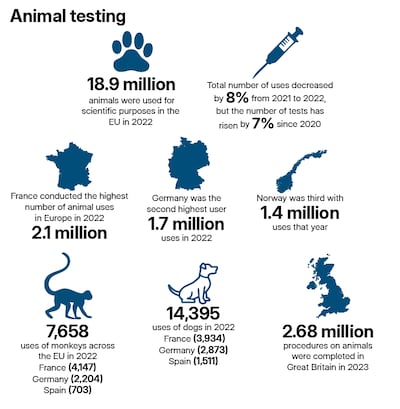

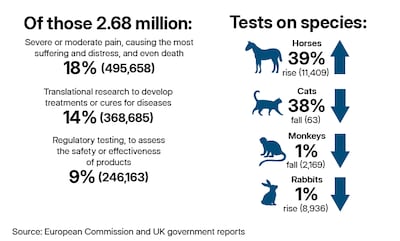

In 2022, about 9.3 million animals were used in experiments in the EU and Norway, with about 40 per cent subjected to moderate suffering and 9.2 per cent facing severe suffering. In the EU and Norway, 12 per cent of the animals were used in research required by regulators, while 33 per cent were used in studies classed as basic research.

Research centres use significant numbers, with the Francis Crick Institute in London using 192,920 animals in 2023. "When there is no non-animal alternative, it is necessary for researchers to continue to develop new complex animal models and experimental platforms, based on the most current data, that reflect human conditions," said Dr Sara Wells, the institute’s chief biological research facility officer.

Drop in numbers

Although the pharmaceutical sector accounts for 20 per cent of animals used in research in Europe, that is down from 30 per cent in 2005, Frontiers in Drug Discovery said in a paper published in April.

The paper’s author, Prof Thomas Hartung of Johns Hopkins University in the US, said the sector "pioneered many alternative methods and been early adopters of new technologies to reduce animal use".

Pharmaceutical company Novartis and external contractors dropped the use of animals in their testing from 500,000 in 2018 to slightly less than 400,000 in 2022. Dr Louahed also confirmed that GSK’s use of animals "decreased by up to 80 per cent" in the past decade. This was largely because of new technology, such as organoids, small organ-like structures generated in the laboratory, she added.

Low success rate

Prof Andrew Knight, a veterinary surgeon and author of the book The Costs and Benefits of Animal Experiments, said that using animals in tests hampered the pharmaceutical sector. He suggested that the low success rate of drugs in clinical trials – during which about 90 per cent fail, according to the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology – was because using animals to test medications gave results that were not applicable to people.

"The drugs that get [to clinical trials] have generally gone through preclinical testing on animal models, but nine-tenths fail at the human stage because they’re not considered to be safe or effective," Prof Knight said. "It indicates animal models are not very predictive for humans."

Many procedures tested on animals are not for purposes that could lead to significant life-saving or welfare benefits for people, campaigners say. For example, what are described as batch potency tests were carried out on more than 150,000 mice in the EU and Norway in 2022, according to figures published by CFI, a large proportion for products including Botox. Toxicity tests and eye irritancy tests are among the most controversial procedures.

Test requirements

Some animal tests are carried out because of requirements by regulators including the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr Louahed said the company "worked with regulators to make sure they accept there are alternatives to animal use", but that regulators in countries such as China tended to retain requirements for animal tests, more than in other parts of the world.

"We’re going step by step to make them more confident … that the data [without using animals] are sufficient," she said. "There’s this change of mindset that’s happened that you hope will be more uniform across the world."

In a statement, Pfizer said: "There are currently no alternatives acceptable to regulatory authorities that fully replace animal research. Any research involving animals is conducted only after appropriate ethical consideration and review. This review ensures that we provide a high level of care to all animals used, and that a scientifically appropriate and validated alternative to the use of animals is not available."

Prof Knight said regulators often required animal tests because "they don’t want to take risks". "Doing something different is a risk," he added. "They need to be looking at the evidence and recognising the high failure of animal models in successfully predicting the outcome for human patients."

While animal studies often require approval from ethics committees, such as those set up by research institutions or universities, he said researchers inflated the probable benefits to gain approval.

"These experiments are routinely being approved on the basis of unfounded claims of their likely human benefits," he said. "Without these claims they probably wouldn’t be approved because they’re invasive, often involving the deaths of animals."

More than a century on from the beginnings of the anti-vivisection movement, the experiments continue, as does the debate surrounding them.