About four million people in Syria face being cut off from vital UN aid on July 10.

Many already endure hunger and rely on the global organisation for even the most basic sanitation.

A UN Security Council resolution on the supply of aid through Bab Al Hawa, the border crossing through which most foreign relief enters Syria, expires on July 10. The council has not yet voted to extend it.

Russia has called for aid to pass through Damascus, which is controlled by the Syrian government.

Maryam, 55, is among the residents of Al Karama camp who waits each month to receive a box of food aid.

“If aid stops, we would starve,” she said.

She described a life spent waiting for essential supplies.

If the aid was delayed by even a few days, she would be forced to ask relatives for help.

“Every day I have to cook two kilos of rice. My husband is dead and I have 11 children who have no one to look after them but me,” she said.

The food box contains an assortment of staple foods, including rice, sugar and chickpeas.

“If there’s no food aid, we’ll have nothing to eat," Maryam said.

She is one of many women forced to live this way. Families of up to 25 people face similar circumstances.

“We hope that food aid will not stop because many people, including me, are in need of it," she said.

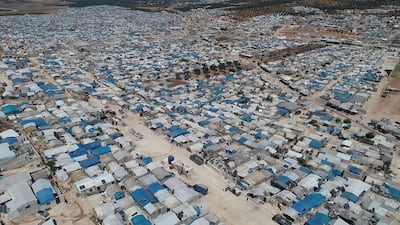

In these crowded camps of displaced people in north-western Syria, millions of civilians wait to discover whether aid will continue to flow through the border crossing.

If the UN fails to reach a decision on the matter, millions will be at risk of starvation.

The Syrian Response Co-ordination Group provides data and updates for humanitarian organisations.

It called on the international community to "fully assume their humanitarian and moral responsibilities towards the Syrian file".

It also emphasised the need to prevent Russian attempts to stop humanitarian assistance from passing through the crossing to reach about four million people..

Between the start of the year and early June, 5,000 of the 9,500 lorries that travelled into northern Syria passed through Bab Al Hawa, said Mazen Alosh, public relations officer for the crossing.

He said 73 per cent of the lorries contained food, while the remaining comprised essentials such as tents and medical supplies.

“For United Nations convoys, it is possible for 70 to 120 trucks to enter within one or two days,” he said.

Their work at the crossing is limited to co-ordinating and helping aid pass through and ensuring that materials reach their destination safely, he said.

“Procedures are very simple and there are no charges on any relief shipment involved,” he said.

"We secure the crossing of relief trucks from Bab Al Hawa to the Turkish side, which return later loaded with goods from warehouses in the Turkish city of Reyhanli. This process takes about six or seven hours."

He said the UN served the entire north-western region of Syria, including northern Aleppo and parts of Idlib, after Turkish military operations in the area.

Mr Alosh said the region faced humanitarian and economic crises that would affect millions of people who depend on UN aid.

"Neither the commercial movement nor the relief trucks from Turkish associations or local organisations or the movement of patients and passengers will be affected. If aid stops, the only impact it will have is the families who depend on the food aid," he said.

Yamen Al Khair, food aid project co-ordinator at IYD Humanitarian Relief Association in north-west Syria, said families would be hit hardest.

For his organisation, that represents about 62,000 families.

He said the end of humanitarian convoys would have an effect on the local economy.

“Materials which arrive free of charge have a significant positive impact on the local market and the prices of available goods," he said.

When the food aid stops, the price of food will rise, placing further strain on people in need.

“It will inevitably affect employees in projects who will lose their jobs,” he said.

Those fortunate enough to have jobs in an area with high unemployment are already supporting several relatives, he said.

“Everyone associated with these projects will be affected by the consequences of its suspension," he said.

He said the need for aid has increased after people were displaced in rural southern Idlib and Hama's northern countryside in mid-2019 because of Syrian and Russian military offensives.

Alternative plans, such as providing assistance through joint crossings with the Syrian regime, are "bad plans and do not meet needs", he said.

“Neutrality is one of the most important principles of humanitarian work.”

He said the regime could not be a positive force in relief efforts because it was responsible for the displacement and suffering of people.

Most of the people in the area are poor and live in harsh conditions, said Shadi Muammar, director of Al Muthanna camp on the border with Turkey.

About 210 families live in the camp, which is home to 300,000 people.

“Most of the families here depend mainly on food aid,” he said.

He said that when residents heard aid could stop, many felt despair.

“We appeal to the international community to extend this decision and stand up against Russia and demand the extension of the United Nations project,” he said.

“Food aid is barely enough to cover the needs of people here. If there were two boxes instead of one, which may not be enough to meet the needs of the camp’s inhabitants.”