An agreement on Lebanon and Israel’s contested maritime border has been reached, months after an effort to avert escalation between the hostile neighbours sparked the revival of indirect negotiations.

Both sides have announced their agreement, although the deal has not been officially signed. Lebanese officials announced on Monday that a signing ceremony would take place in the last week of October in Naqoura, where Unifil, the UN's peacekeeping mission in Lebanon, has its headquarters.

Why is the maritime demarcation deal significant?

The dispute over the Lebanon-Israel maritime area is a long-running one, with several rounds of US-mediated negotiations having taken place since 2007.

The agreement has been touted as a historic breakthrough by officials on both sides.

Israel hopes its gasfields will fill the European energy gap left following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine while Lebanon hopes the discovery of hydrocarbons could help to lift the struggling country out of a protracted economic crisis.

The agreement was also lauded for staving off the possibility of an armed conflict between Israel and the Iran-backed Hezbollah group, a powerful militia organisation.

In June, the group threatened to attack after Israel moved a drilling vessel to a gasfield partially claimed by Lebanon.

What is the deal?

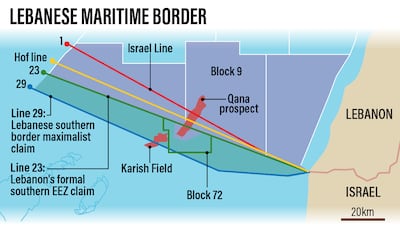

The maritime border will intersect through a prospective gasfield known as Qana, a demarcation known as Line 23.

The deal gives Israel full control over the previously contested Karish gasfield south of Line 23, which Lebanon had staked a partial claim to. Theoretically, it gives Lebanon the prospective Qana field.

Although not officially made public, a leaked copy of the US-mediated deal has circulated. The agreement, a copy of which was sent to both countries by US mediator Amos Hochstein, states that the deal “establishes a permanent and equitable resolution of their maritime dispute”.

Lebanon’s politicians, too, have marketed the maritime deal as preserving Lebanon’s full sovereign rights.

But in reality, the agreement “contains a lot of ambiguous articles, which will create problems in the future”, said Marc Ayyoub, energy researcher at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs.

Qana ownership 'between brackets'

“Lebanon has got the ‘ownership’, between brackets, of Qana,” Mr Ayoub said, referring to the area designated for oil and gas exploration. “But the agreement includes a financial agreement that is being currently discussed between Israel and the operator of block nine, Total.”

Under the deal, Lebanon would take possession of the entire prospective Qana field in exchange for ceding its claim to Karish, where Israeli operations to begin drilling have already begun.

But that ownership comes with an asterisk: under the terms of the agreement, French energy company TotalEnergies must give Israel a share of any future profits from the Qana prospect.

This means Israel and Total must agree on the terms of financial compensation before Lebanon can begin extraction.

This makes Lebanon's ability to explore and develop the prospect contingent on Israeli approvals, pending agreement over the financial arrangement.

Israel Prime Minister Yair Lapid last week stated that Israel would “receive approximately 17 per cent of the revenues from the Lebanese gasfield, the Qana-Sidon field, if and when they will open it”.

However, Mr Ayoub maintains that the deal is the best Lebanon could hope for, given its geopolitical standing and economic constraints.

“Bigger picture, the agreement removes the political and geopolitical hurdles” from developing its gas wealth, he said.

What happens now?

Both Lebanon and Israel have announced their public approval of the deal. The two rival states must now submit official letters registering their agreement to the US. After that, they will each submit co-ordinates of the maritime boundary to the UN.

A signing ceremony is expected to take place at the end of October in Naqoura, which straddles Lebanon and its southern neighbour.

To avoid conflict over the disputed land border, the two neighbouring countries have agreed to begin the maritime demarcation five kilometres into the sea, until the land dispute is resolved.

Lebanon’s best-case scenario

Lebanon’s politicians have promoted the benefits of the maritime agreement, presenting it as the key to the nation’s financial recovery.

But that remains to be seen.

“For years, we have been dreaming of Lebanon becoming an oil and gas-producing country,” lead negotiator and deputy Parliament speaker Elias Bou Saab said on Sunday. “We must exploit this energy today.”

Energy experts, including Mr Ayoub, are cautious about the odds. While Israel will immediately begin the process of extracting gas from the Karish gasfield, Lebanon’s Qana is merely a prospect — which means there is only a 20 to 25 per cent chance the first well drilled would contain viable amounts of hydrocarbons.

“And this is why we really can’t say today that Lebanon has become an oil-producing country or a gas-producing country because of this agreement,” Mr Ayoub said.

The process of exploring and developing a gasfield is lengthy. Assuming the first well is viable, the process of developing the field would take between three and six years.

“We won't see money and gas flowing from that field for well beyond that,” Mr Ayoub said. “And that’s assuming there are no border tensions and no political and administrative delays.”