Turkey’s farmers are facing catastrophic levels of drought despite rains that initially staved off panic at the start of the year as reservoir levels shrunk to less than a quarter of their capacity.

Water levels around Istanbul – home to about a fifth of Turkey's population – fell to less than 25 per cent of their full capacity in January after months with no rain. Officials issued a warning at the time that the city would run out of water in 45 days.

TV bulletins switched between footage of people praying for rain and maps of the country coloured a deep red to indicate dire groundwater conditions.

The heavens later opened, soothing public fears, but groundwater levels were not sufficiently replenished, leading to the appearance of cavernous sinkholes across Turkey’s agricultural plains.

“Unfortunately, we only wake up when the water level of the dams that feed the cities drops and ask: ‘What’s happening?’” said Akgun Ilhan, a water management expert at Istanbul Policy Centre.

“When it rains for a few days and water collects in the dams, we go back to sleep.”

Experts said the country still faced a severe drought and farmers called on the government to declare a natural disaster.

The hardest-hit area, the South-eastern Anatolia region, recorded a 90 per cent drop in rainfall last month compared with April 2020, according to the Water Policy Association in Ankara. Across the country, there was half as much rain as the previous year.

The impending water crisis led President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to unveil a new water watchdog in March, along with $645 million in funding for new dams, water treatment plants and irrigation.

Agriculture Minister Bekir Pakdemirli had already told the public to treat water as a precious commodity “just like gold or a piece of jewellery".

Climate change plays a significant role. Turkey has faced several droughts since the 1980s owing to population growth, accompanied by rapid industrialisation and urbanisation.

Turkey’s water infrastructure has struggled to keep up, with 50 per cent of water lost to leaks before reaching the tap, the Water Policy Association said.

Data from the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works shows available water levels steadily falling, from about 1,650 cubic metres a person in 2000 to less than 1,350 cubic metres last year.

The UN classes a country as “water scarce” at 1,000 cubic metres.

Mr Ilhan called for Turkey to reduce carbon emissions, which she said had increased by 135 per cent in the past 30 years. It is one of the few countries not to have ratified the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change.

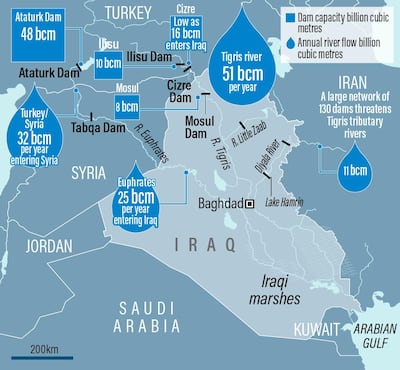

To the south of Turkey, Iraq and Syria have long complained of water shortages caused by Turkey's extensive damming of the Euphrates and Tigris under the Southeast Anatolia Project, a $32 billion plan initiated in the 1970s that is focused on providing hydroelectric power and farm irrigation.

The project, known by its Turkish acronym GAP, was to provide irrigation for an additional 18,000 square kilometres but has only achieved about half that, according to Abdullah Melik, chairman of Sanliurfa province's Chamber of Agricultural Engineers.

“GAP has been 54 per cent effective in agricultural irrigation [but] the project was not completed,” he said.

Nearly three quarters of Turkey’s water consumption goes to agriculture and farmers say this year’s yield of crops such as wheat, barley and lentils have been reduced by at least a fifth.

“The state must immediately declare the region a disaster area,” said Mehmet Ali Dogru, chairman of the Chamber of Agriculture in Nusaybin, a town on the Syrian border.

“GAP needs to be completed as soon as possible so that we do not suffer from drought.”

Turkey has not shied from holding its control of the Tigris and Euphrates over Iraq and Syria, such as cutting off the Euphrates when Iraq invaded Kuwait and coercing Syria into halting support for Kurdish insurgents.

This year, Turkey has allegedly halved the flow of the Euphrates, primarily affecting areas controlled by the Syrian regime and the Kurdish-led authorities. Ankara denies the claims.

GAP has allowed Turkey to control "the most pivotal rivers in the Middle East and, for some, declare its hydro-hegemony", said Dr Arda Bilgen, water politics expert and visiting scholar at Clark University in the US.

“Syria and Iraq also worried that the project would severely impact the quality and quantity of their water.”

The outbreak of the civil war in Syria "further complicated efforts to co-ordinate and co-operate over water resources management", he said.

Dr Bilgen, who has extensively researched GAP, said its effect locally was “ephemeral, fragile and unsustainable rather than long-term, inclusive and sustainable".

While benefiting "those already possessing large amounts of land, capital, resources and power", GAP has cost small landholders and seasonal workers, and its dams have displaced up to 400,000 people, he said.