Iraq’s new President Abdul Latif Rashid and Mohammed Shia Al Sudani — his nomination for prime minister, tasked with forming the next government — are unlikely to fulfil public expectations of reform, according to experts.

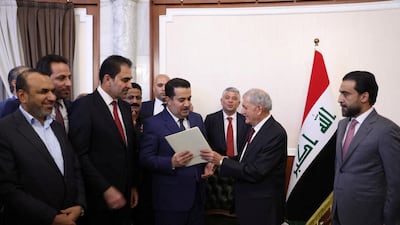

Parliament elected Mr Rashid, a veteran Kurdish politician and former minister, as president on Thursday, after a year of political deadlock.

Mr Rashid then nominated Mr Al Sudani as prime minister.

Politicians affiliated with Shiite cleric and politician Moqtada Al Sadr had emerged as the largest bloc in a general election last October but fell short of a majority.

Mr Al Sadr was unable to muster enough support for his choice of president in the face of challenges from the rival Co-ordination Framework bloc, made of up largely of groups backed by Iran.

Omar Al Nidawi, programme director at the Enabling Peace in Iraq Centre, a US-based non-government organisation, said the profiles of Mr Rashid and Mr Al Sudani — who was backed by the Co-ordination Framework — did not suggest they would shake up Iraq's long established political system.

“The Rashid-Sudani government is another product of Muhasasa and shady dealings among a deeply corrupt political elite,” Mr Al Nidawi told The National.

Muhasasa is the political system introduced in 2003, after dictator Saddam Hussein was toppled in a US-led invasion.

Under Muhasasa, political groups share out posts based on sect, ethnicity and religion, regardless of election outcomes.

“There’s nothing about their affiliations, records or characters that suggests they would be bold reformers who put the national interest before partisan interests and personal gain,” Mr Al Nidawi said.

Renad Mansour, director of the Iraq Initiative at London's Chatham House think tank, said Mr Rashid and Mr Al Sudani would owe allegiance to the political parties who put them in power, and were therefore bound to the ruling elite.

“I do think that they will continue to do what the two positions are meant to do, but I don’t think this is a reform movement in Iraq — we shouldn’t be expecting much change,” Mr Mansour told The National.

“They will not really fulfil the public's expectation,” he said, adding that it would be difficult for them to “live up to the job”.

To become an “excellent” prime minister, Mr Al Sudani “must manage all these parties and their interests within the government”, said Sajad Jiyad, an Iraq analyst with the Century Foundation think tank.

“He must push through much needed reforms without having significant political capital, but he doesn’t have a huge number of seats or a political party,” Mr Jiyad said.

Instead, Mr Al Sudani is “relying on all these bitter enemies deciding, 'OK, we will keep them in power,'” he said.

Mr Al Sudani's first task is to present a Cabinet line-up that will get Parliament's approval, for which he has 30 days.

Michael Knights of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy think tank said Mr Rashid and Mr Al Sudani were capable of fulfilling their formal duties.

“The question is whether they can exceed their predecessors in terms of resolving thorny political problems that require risk-taking,” Mr Knights said.

These problems include the threat from militias, the energy dispute between Baghdad and Iraq's semi-autonomous Kurdish region and climate change, he told The National.

Mr Knights pointed out that Mr Rashid was a hydraulic and civil engineer, who headed the Ministry of Water Resources between 2003-2010.

“So, he will hopefully take up the water issue with special enthusiasm,” Mr Knights said.

But the public's “expectations of any politician are very low, so they can meet that low bar”, he added.