For many, Iraq's short-lived monarchy was the golden era of a country that has since been marred by decades of war and instability.

Founded in 1921, it rose from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, which Arab forces helped topple, motivated by the promise of an independent nation, free from external influences.

But when it came time to establish an independent state, as agreed with Hussein ibn Ali, the Sharif of Makkah, leaders in Europe had other ideas.

After the British withdrew their support for a unified Arab state that included Palestine, Hussein's son, Faisal, declared a Kingdom of Syria in March 1920 that covered modern Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan and Syria. But the new monarchy crumbled in less than six months, having been rejected by the local populace and crushed by the French military, who held a mandate in Damascus.

Meanwhile, in Iraq, where the British had established a mandate, locals had begun to revolt against foreign rule and launched attacks against the army.

A new king begins a new era

The following year, the Cairo Conference was held to decide the future of the region. Britain, led by Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill and advised by TE Lawrence “of Arabia”, saw an opportunity to maintain indirect control over Iraq and appointed Faisal, who had fled to London, King of Iraq.

The first order of business was to endear a Hejazi prince – from western Saudi Arabia – to the local and diverse population of Iraq. He arrived to the country via Basra port and took the train to Baghdad. On his way, Faisal visited the cities of Hillah and Kufa, plus Karbala and Najaf, where revered Shiite Imams are buried – in an effort to garner support from the Shia community.

historian

“Then, Iraqi dignitaries and majority of senior religious leaders from both Shiites and Sunnis pledged allegiance to the King,” historian Yassir Ismaiel Nassir told The National.

“He enjoyed wide acceptance among local communities in Iraq due to his direct lineage to the Prophet Mohammed,” Mr Nassir said.

In an important gesture, he choose August 23 as his coronation day to coincide with Eid Al Ghadeer – a key date for Shiites as it was when the Prophet Mohammed declared his cousin, Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, to be his successor.

With the establishment of the monarchy, a new and important chapter in Iraq’s modern history began. The king got to work transforming the country from a entity comprised three Ottoman provinces – Mosul, Baghdad and Basra – into a state with a with a national regime.

During his 12-year rule, King Faisal I laid the foundations for government institutions that exist to this day, earning the title “Founder of Modern Iraq”.

He established Ahl Al Beit University in Baghdad’s Azamiyah district, which remains under the name The Arab University.

He encouraged Syrian exiles to work as doctors and teachers in Iraq, among them Sati Al Husari, a writer who became the general director of the education ministry.

Under his reign, plans were in place to link Baghdad, Damascus and Amman by rail and he aimed to build an oil pipeline to the Mediterranean through Syria.

Iraqis remember him as a modest king, who would mingle with the public. His main goal was to achieve full independence for Iraq.

In 1930, Iraq and Britain signed a treaty to establish a close alliance between the two countries but also give Iraq a degree of political independence. It eased British control but also gave it rights to station and move military forces in Iraq – as well as full control of Iraq's oil resources.

Two years later, the British mandate ended and Iraq gained independence, becoming the 57th member of the League of Nations.

“The King was clever. Despite his differences with Britain, he tried to grab independence from them in any form he could,” Mr Nasir said.

“Despite the hardships he faced during his reign, he succeeded in leading the country to safety and laying the foundations for a modern state.”

In 1933, aged 48, Faisal I died of a heart attack and his son, Ghazi, ascended the throne.

King Ghazi ruled for just six years before he died in a motor accident in Baghdad, passing the throne on to his 3-year-old son Faisal II.

Faisal II's uncle, Crown Prince Abdullah, held power until the boy completed finished his education in Britain's Harrow boarding school, where he studied alongside his cousin, King Hussein of Jordan – father of the country's current king, Abdullah.

King Faisal II ascended the throne aged 18, in 1953. High hopes were placed on the young king to build on his father and grandfather's legacies.

However, the British colonial power that established the Hashemite kingdom in Iraq had not accounted for the country's diverse ethnic and religious communities, including a large Shia and Kurdish population.

Many minorities felt marginalised by a Sunni Arab king – a theme that continues to influence the country's stability today.

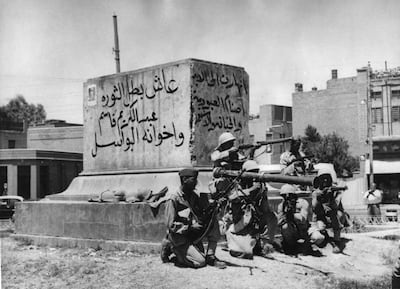

In July, 1958, the monarchy was overthrown in a military coup, led by the Free Officers Movement. King Faisal II, his uncle and other family members were killed. The group had been inspired by the 1952 Egyptian Revolution that saw its monarchy abolished in favour of a more secular and nationalist state.

How is Iraq's era as a kingdom viewed today?

Despite only lasting 37 years, many view Iraq's monarchy as a positive period in the country's history.

Feisal Al Istrabadi, Iraq's former UN ambassador, said the monarchical system presented “an optimistic and hopeful movement in Iraqi history, one that was lost and that cannot be replaced.

“The monarchy found Iraq, a backward, forgotten corner of the Ottoman Empire, and in less than 40 years turned it into a state that mattered in the power equations of the region,” he told The National.

Under the monarchy, Iraq became a central regional player in international politics, including America’s fight to stop the spread of communism, he said.

“Of course, in 1958, the new dispensation chose the Soviet Union, the losing side in the Cold War, and we know the rest of the history of Iraq.”

To the British, the monarchy was thought to be an institution that would inspire loyalty, and unite a diverse society, thus making it a foundation for nation-building, said Charles Tripp, Professor of Middle East Politics at London’s SOAS university.

“This was one of the many contradictions of their policy – the stronger a sense of Iraqi nationalism became, the less justification there was for having a monarch at all, especially one from a Hejazi dynasty,” Mr Tripp told The National.

He said the British wanted the monarchy to be constitutional and “their own style of indirect rule”, which undermined its legitimacy.

The king’s dependence on British was “pretty obvious to all Iraqis and made him the effective centre of a web of patronage and class privilege”, Mr Tripp said.

After the Second World War, Iraq's society became increasingly mobilised with Iraqi and Arab nationalism, communism and socialism.

“None of which had any tolerance of continued British influence or of the monarchy that was so obviously a British creation,” Mr Tripp said.

He said this was why Iraq’s kingdom only lasted 26 years after the country’s independence from the British mandate in 1932.

Authoritarian nostalgia among Iraqis

When Mr Al Istrabadi went to Baghdad in July 2008, the prevailing feeling among Iraqis was that only suffered after the coup.

“Even diehard communists and leftists at the time of the coup spoke against it,” he said.

“I do not know many Iraqis who would not undo the 1958 coup if they could.”

He said the monarchy was “looked back upon wistfully by most Iraqis”.

Harvard Kennedy School

A trend has emerged in Iraq in recent years for authoritarian nostalgia, said Marsin Alshamary, research fellow with the Middle East Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School.

“Authoritarian nostalgia takes on different forms in Iraq: sometimes it’s thinking life was better under Saddam Hussein and sometimes it’s Abdel Karim Qasim [the military leader who overthrew the monarchy].

“Recently it’s been the question of whether the monarchy would have been better,” she said.

“Young Iraqis perhaps think of the monarchy as being a better time because it has all these superficially appealing aspects — the single “strong” leader (as opposed to the politicking they witness among the many political actors today),” Ms Al Shamary told The National.

“All these things appeal to young Iraqis, who have not lived through traditional authoritarianism,” she said.

“The gist of it is, people in Iraq are nostalgic for the past because they don’t have the same tools to assess the past with which they can assess the present, but that’s not unique to Iraqis.”