Millions of Iraqis face an intolerably harsh summer, with Turkish dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers compounding a year of low rainfall.

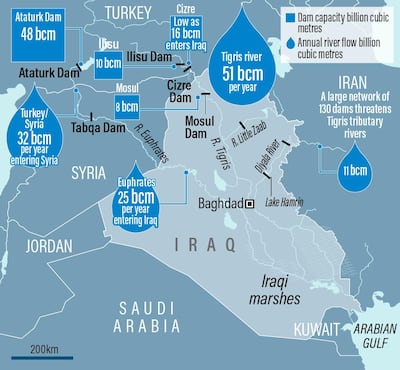

The rivers, which account for more than 90 per cent of Iraq’s freshwater, were at historically low levels following scant winter rainfall in the region and snowmelt mainly in the mountains of Southern Turkey, which feeds into the rivers.

Turkey says it is also facing a drought and dwindling water supplies, but stands accused of holding on to supplies in its dam reservoirs.

On 7 May, Syrian Minister of Water Resources Tamam Raad called on Turkey to release more water from the vast Ataturk Dam.

On 21 May, Iraq’s Ministry of Water Resources said Turkey had released some water, but emphasised that the situation was a crisis.

In the capital Baghdad, photos of the Tigris showed an almost non-existent river.

“Is there a crisis? Yes, there is a real crisis,” Minister of Water Resources, Mahdi Rasheed Al Hamdani, told a press conference this month.

Water flow rates in both rivers have halved from the same period last year, Mr Al Hamdani said.

The historical trend has also been one of decline. According to Iraq’s Ministry of Water Resources, water flowing into Iraq has dropped from a 1970s peak of nearly 80 billion cubic metres per year to less than 50 billion cubic metres.

One reason for that decline was a network of 22 Turkish dams that scaled up with the completion of the Ataturk Dam on the Euphrates in 1990 and the recently completed Ilisu Dam on the Tigris. Climate change has also worsened the crisis.

Worsening drought

As summer approaches, upstream dams in Iran have also shrunk the Tigris tributaries, cutting off flow at the Diyala river and decreasing the flow of the Lower Zaab river by 70 per cent, causing a “big crisis” in Diyala province, Mr Al Hamdani added.

“For sure, the situation is worrying,” Mr Al Hamdani said.

Experts and officials told The National that the effect of this plunge in water levels could destroy the ecology, worsen household water quality, which in most areas is already unsafe to drink, and increase soil salinity, leaving barren land that was once fertile.

“The dropping water levels will impact irrigated agriculture with less water flow, which can seriously impact food security, while the drought also could make vegetation more susceptible to wildfires,” said Wim Zwijnenburg, environment and conflict expert.

Agricultural progress after bumper harvests in 2019 “can be easily undone this summer,” said Mr Zwijenburg, a UN Green Star winner.

Declining harvests

In Diyala, northeast of Baghdad, farmers are counting their losses.

The man-made Lake Hamrin, Diyala’s main water source, has lost nearly 70 per cent of its water, according Ahmed Al Zarkoshi, the mayor of Al Saadiyah district.

Lake Hamrin currently holds about 350 million cubic metres of water, down from nearly 3 billion cubic metres in 2018, Mr Al Zarkoshi said.

Over the past three weeks, the lack of water has forced some of the province’s 400 water projects to stop for a few days or work less than their capacity, said the spokesman of the provincial Water Resources Department, Emad Salih.

Sheik Ahmed Thamir expects the worst.

"The current situation is miserable," Mr Thamir, a 50-year-old farmer, told The National.

Out of 1.25-million-square-metres of land planted in November, he now only has 375,000 square metres of wheat, and vegetables in another 100,000 square metres.

To cope with the shortage of water, the Agriculture Ministry has prevented planting rice, corn and vegetables in the summer, allowing only water to reach orchards of palm trees and fruit.

“There is no water for our lands, our livestock and for us to drink,” he said, adding that the residents buy potable water in tankers or jerrycans.

“Those who can afford digging wells will stay in their lands to feed their cattle and make a living from them, but those who can’t will definitely leave for the cities to seek jobs such as construction workers,” he added.

For years, Iraq has been struggling to reach agreements with Turkey and Iran that allow a fair volume of water, but implementation has proven elusive.

Mismanagement of water resources in Iraq, including inefficient flood irrigation methods, rundown water pipe infrastructure and the growing of water-intensive crops such as rice, compound the problem.

As Iraq failed to address these problems over years of sanctions and war, the combined reservoir storage capacity of upriver dams has grown.

In Turkey, storage capacity could be as high as 94 billion cubic metres of water, more than the combined annual flow of the Tigris and Euphrates.

But on all of the dams on the Tigris and Euphrates, evaporation rates are getting higher as global temperatures rise. Low rainfall could complicate efforts to reach agreements.

Destroyed ecology

Iraq’s southern marshes were declared a Unesco world heritage site in 2016, but “indications for drought started last week,” warned a leading Iraqi NGO.

“I believe that there will be a big problem this summer even worse than what we saw in 2009, 2015 and 2018,” said Jassim Al Assadi, the managing director of Nature Iraq NGO.

Iraq’s famed marshes, home to the unique Marsh Arab culture, provided a natural shelter for rebels against former dictator Saddam Hussein in the early 1990s.

Saddam later drained them and displaced the inhabitants.

But after being revived after 2003, the fragile ecosystem almost disappeared in 2015 after prolonged drought.

Higher levels of soil salinity, which occurs naturally but can create a toxic environment at high levels, are impacting the lives of local Marsh Arab buffalo breeders, Mr Al Asadi said.

As their buffalos become sick, many choose to move to the city despite the risk of unemployment, putting even more pressure on strained government services.

“We have to set off the alarm now to prepare ourselves. We act when everything has perished,” Mr Al Asadi said.

Boiling point in Basra

In 2018, over 100,000 people fell sick in the southern port city of Basra by poor domestic water supplies, leading to widespread protests.

Apart from oil pollution uncovered by Human Rights Watch, one of the causes of the mass poisoning was high water salinity, HRW said. The Shatt Al Arab, where the Tigris and Euphrates meet before entering the Gulf, was at a low ebb.

That led to high tides from the Gulf pushing seawater far inland.

Power stations and water treatment plants that take water from the Shatt Al Arab, already struggling due to lack of maintenance, were not designed to cope with high salinity. Meanwhile, farmland became infertile.

“Salinity will affect the cooling systems of the thermal power stations in Basra region,” said Harry Istepanian, Iraq energy expert and consultant.

That could lead to more power plant failures through central Iraq, Mr Istepanian said. Living conditions in Basra and other cities would worsen as summer temperatures surpass 50 Celsius.

Public health in Basra could be again impacted as water levels drop because of local environmental mismanagement including the dumping of sewage and oil spills, Mr Zwijnenburg said. Water pollution would become more concentrated.

“Basra has seen various initiatives, both by international organisations and national charities that put resources into building and repairing water filtration, purification and desalination plants,” Mr Zwijnenburg says.

“We will now see if that work is paying off.”

But even if such projects manage to stablise Basra's situation this year, the long term trends are worrying for the rest of the country, Mr Zwijnenburg said.