Scientists have made the “ground-breaking” discovery of a miniature whale species that lived in the sea that covered present-day Egypt about 41 million years ago.

Named Tutcetus rayanensis, the ancient creature was about 2.5 metres long and weighed about 187kg, making it the smallest known basilosaurid whale, according to researchers.

Despite its small size, Tutcetus rayanensis has provided significant insights into the history of early whales. And it is the oldest whale of that type to be recorded in Africa.

Researchers believe the basilosauridae, a group of extinct, fully aquatic whales, represent a crucial stage in whale evolution, as they transitioned from land to sea.

They developed fishlike characteristics, such as a streamlined body, a strong tail, flippers, and a tail fin, and had hind limbs visible enough to be recognised as legs, which were not used for walking but possibly for mating.

Hesham Sallam, a professor of vertebrate palaeontology at the American University in Cairo and founder of the Mansoura University Vertebrate Palaeontology Centre, was the leader of the project.

“During the middle Eocene, the warm, shallow marine environment of Egypt's Western Desert likely played a role in shaping Tutcetus's small size and characteristics.

“This discovery shifts our perception of whale distribution and migration by suggesting that (sub)tropical regions, like Egypt, served as pivotal zones for early whale evolution and diversification.”

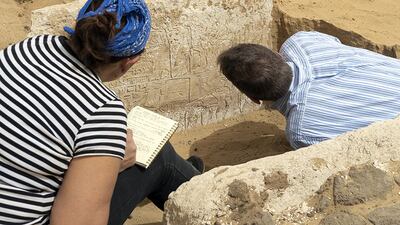

Saqqara discovery in Egypt – in pictures

The new discovery was made in the middle Eocene rocks and it helps to illuminate early whale evolution in Africa.

“Tutcetus's emergence during the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum (LLTM) underscores the link between climate change and evolution,” Mr Sallam added.

“The global warming during LLTM potentially influenced the transition to aquatic lifestyles in marine creatures.

“This finding accentuates the sensitivity of species to environmental changes and showcases the potential role of climate shifts in driving evolutionary adaptations.”

The whale’s name draws inspiration from both Egyptian history and the location where the specimen was found.

Tutcetus, combines “Tut” – referring to the famous Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun – and “cetus,” Greek for whale, highlighting the specimen’s small size and subadult status.

The name is also a nod to the discovery of the king’s tomb a century ago and coincides with the impending opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza.

The species name, rayanensis, refers to the Wadi El Rayan protected area in Fayyum where the specimen was found.

The specimen researchers found consists of a skull, jaws, hyoid bone, and the atlas vertebra of a small-sized, subadult basilosaurid whale which was embedded in an intensively compacted limestone block.

“The relatively small size of Tutcetus is either primitive retention or could be linked to the global warming event known as the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum,” study co-author Sanaa El Sayed, a doctoral student at University of Michigan and a member of Sallam Lab, said.

“This ground-breaking discovery sheds light on the early evolution of whales and their transition to aquatic life.”

Through detailed analyses of Tutcetus’s teeth and bones, and CAT scans, the team was able to reconstruct the growth and development pattern of this species.

“The discovery of Tutcetus fostered increased paleontological exploration in Egypt and beyond, focusing on rich fossil deposits,” Mr Sallam said.

“This finding encourages the study of older geological layers through techniques like stratigraphy, CT scanning, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

“These efforts may unveil older assemblages of early whale fossils, enriching our understanding of their evolutionary journey.”

The findings are published in the Communications Biology journal.