On an archaeological site dotted with sunshades in the seaport of Sidon, a hot, tired and increasingly frustrated Dr Claude Doumet-Serhal stood watching the progress of a mechanical digger clearing out the backfill.

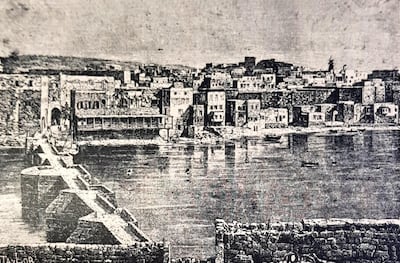

She had come to southern Lebanon in the summer of 1998 to see whether her hunch was right that the modern metropolis and the mysterious ancient capital of the Canaanites and Phoenicians were one and the same.

More than a month in, however, the Lebanese-British mother of three had yet to unearth anything that proved the lost city hitherto referenced only in mythology and scripture was buried tantalisingly somewhere beneath her feet.

“Zero,” Doumet-Serhal, 66, tells The National of her quest to sift through the build-up of soil and detritus left by previous archaeologists. “I worked with an excavator, which I had never done before. There was so much backfill. I wanted to get to the lower layers.

“I found marble statues, including a superb one of Hermes, and a fridge thrown in; the antique and the new. But, from an archaeological perspective, there was nothing. My anguish was metaphysical.”

Doumet-Serhal had been given permission by the Lebanese Directorate General of Antiquities to dig in the heart of Sidon on three plots of land expropriated in the 1960s for research but left untouched because of the country’s civil war.

As site director, the collaboration with the British Museum began as a four-by-four-metre hole on a spot of her choosing within the walls of the medieval city, although others thought the nearby Crusader castle might be more fertile ground.

The first find

Only days before her colleague John Curtis, the museum’s Keeper of the Middle East Department, arrived to monitor developments, Doumet-Serhal was surprised – and not a little relieved – to find herself cradling a pinkish coloured bowl.

“I found a weirdly shaped ceramic. Combed,’’ she says, referring to the decorative markings on the surface of the Canaanite pottery. “and typical of the third millennium BC. I rang a friend, who said: ‘You’re dreaming, hallucinating. It must be Byzantine.’

“But nobody knows the ceramics of the area like me. That’s how it happened – from [the planned] two years, we stayed for 27.’’

The find would revolutionise understandings of Lebanon's ancient history. Although the Canaanites built cities across the Levant in Lebanon, Israel, Jordan and Syria about 4,000 years ago, they left no surviving written records.

All that was known of Sidon had been gleaned from second-hand sources, not least the Old Testament, and the ancient Greek poet Homer and historian Diodorus of Sicily, who wrote of its famed Persian pleasure gardens.

'It's the big picture that's extraordinary'

From that day, a trickle of further discoveries allowed Doumet-Serhal to piece together the story of one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities and its enigmatic residents.

Analysis of fragments of textiles, pollen, animal bones, wood and grain gradually began to shine a light on the citizens’ bustling coastal trade networks, various customs, dietary habits and the prey they hunted.

The difference between Doumet-Serhal's approach and the colonial treasure hunters of the past is obvious from her enthusiasm for a piece of ancient fabric no bigger than the tip of a finger and the revelations held within its fibres.

“If you find a beautiful object, you die of joy," she says over tea at her home in London. "I found 173 tombs. You can imagine the beautiful things in there – jewels, gold. But it’s not about only the object. It’s about everything they did, the culture, the rituals, the food. Who would have thought they would find hippopotami, bears and lions in the third millennium BC?

“It’s the big picture that’s extraordinary. When you build it up from small things and it grows and grows with you. The most rewarding thing is the big picture.”

Long national unity

The discoveries not only changed our understanding of how the ancients lived on the Eastern Mediterranean coasts but also dramatically revealed that the modern Lebanese were, in fact, their direct descendants.

DNA testing on five Bronze Age skeletons uncovered at the site shows that the present-day population derives 93 per cent of their ancestry from the Canaanites despite the intervening cultural upheaval, wars, conquests and migration.

Doumet-Serhal can’t help but point out the relevance of such long national unity as her compatriots, for all their religious and political differences, emerge from the country’s third major conflict in 50 years.

The debate about Phoenicia has been at the heart of Lebanese history and identity in a region where the ancient world inspired nationalisms in Egypt, Syria, Israel, Palestine and Iraq.

“It’s not about stones. It’s about the people of Lebanon,” she says. “Maybe this could help them understand that before there was Christianity, and before there was Islam, and before there were any of the religions they belonged to, they actually are the same people that lived on this same land since the end of the fourth millennia BC.”

The devotion with which Doumet-Serhal has studied the influences leading to modern Lebanon can be traced back to her grandfather, Michel Chiha, the banker and newspaper editor whose ideas shaped the country’s constitution. Her role as head of the foundation that bears his name is a cause close to her heart as it seeks to preserve and promote the principles by and for which he lived and fought.

Levels of successive archaeology

“Lebanon is all continuity,” she says. “That’s what was incredible about Sidon. The levels of successive archaeology, that continuity.’”

Born in Beirut in 1958, Doumet-Serhal recalls wanting to be an archaeologist from about the age of 11 or 12 though can’t quite explain why.

It may have been the visits to so many ancient ruins, such as the Roman temple of Baalbek, or the fascination with which she viewed the antiquities in private collections, though she has never been interested in acquiring such artefacts herself.

Whatever the reason, young Claude’s precocious ambition of studying the history of humankind through the physical remains left behind was a source of familial amusement.

Field of dreams

“Everybody at home had a little laugh,” she recalls, although citing the strong work ethic instilled by her father for motivating pursuit of the dream.

“For my father, it was always essential that I would have a profession. It really helped me. Having a profession is the essence of my life.’’

When civil war broke out in 1975, Claude, then 16, moved to France with her two sisters and brother, becoming their guardian while undertaking degrees in art history at L’Ecole du Louvre during the day, and archaeology at the Sorbonne by night.

With her father staying in Lebanon and the visits by boat from her mother only intermittent, she can’t help laughing at attending the younger siblings’ parent-teacher meetings as a mere teenager herself.

What pulled Doumet-Serhal through the challenges was a singular friendship with Anne-Marie Maila-Afeiche, the archaeologist she rang after finding the Canaanite bowl at Sidon. Both endured the rigorous educational regime of studying for two degrees at the same time, although Doumet-Serhal specialised in Near Eastern art while Maila-Afeiche focused on the Islamic world.

“We’d come out of the Sorbonne together at midnight. We did everything together. It gave us courage.”

At the Louvre, Doumet-Serhal was taught by Pierre Amiet, the French archaeologist and world authority on the engraved cylinder seals used in the ancient Near East to validate cuneiform documents and mark clay pottery.

It was only decades later that she saw the fruits of all that hard work when dozens of such seals were turned up at Sidon. “Now on my site, I do it all. I study the cylinders, I don’t need to go to a specialist.”

With the war still raging in Lebanon after Doumet-Serhal completed her studies, she worked on excavations in Syria at the ancient port cities of Ras Shamra and Ras Ibn Hani on the north-western coast.

She married a Lebanese doctor, Paul Serhal, who became a pioneer in fertility research, and the couple moved to London in the mid 1980s for a six-month medical posting. As with so many who fled in the exodus, they stayed in their adoptive home a year, then two and then for good.

Colleagues in archaeology assumed that starting a family would end Doumet-Serhal’s career but she proved them wrong, continuously working, exhibiting and publishing.

An immense puzzle

The juggle made the Sidon excavations in particular all the more gruelling as she took the children to stay with their grandparents in Beirut for two months a year while shuttling back and forth to the site 25 miles to the south.

“Everyone would say: ‘Aren’t you warm? Why are you digging in the summer?’ It was 38°C in the shade,’’ she says, recalling her protestations to colleagues that she could handle the conditions.

“In fact, I couldn’t stand it. But nobody knew that I had to come back to London for the start of the school year in September. I had a very supportive husband. He knew it was my life.”

The children, however, did not share their mother’s obsession with the immense puzzle at Sidon. While Doumet-Serhal returned every summer enthused with the continuing search for another missing piece, her offspring showed up only once to be able to say that they had been to an archaeological site.

“They all three hated it. Hated. Hated. They never wanted to hear about it again. They couldn’t understand what I was doing there. It’s not always romantic. It’s dirty. It’s hot. It’s hard. Long hours. Tiring.”

Challenge turns to advantage

Living between two worlds – London and Beirut – for so many years gradually went from being a challenge to an advantage.

“You go back to your roots, and your roots don’t recognise you,” she says. “By dint of living abroad, you’ve changed. You don’t respond to the same things. You become a lot more rigorous, more demanding.

“The war in Lebanon threw us into it. From the beginning, you have to accept that you only belong to yourself. That becomes a great strength.”

A few years into her exile, Doumet-Serhal sought to mobilise the growing community of others similarly displaced, founding the British Lebanese Friends of the National Museum in Beirut in 1993 to raise funds for the badly damaged institution that stood on the front line separating the warring factions.

The first post-conflict viewing, however, held on the 50th anniversary of Lebanese Independence, was somewhat underwhelming. In what was a symbolic reopening of the museum’s doors, the statues and sarcophagi were still encased in double layers of concrete installed during the onset of the civil war by Emir Maurice Chehab, the then director of the Antiquities Department, to protect them from looting.

“Nobody could see anything. All of Beirut was there,” she says, of the guest list which included president Elias Hrawi and the first lady, “well-dressed, and there was nothing other than candles and an exhibition of cubes. People were wondering what they were doing there.”

Living memory of Lebanon

In Doumet-Serhal’s efforts to help revive the National Museum, she consulted Honor Frost, a pioneer in marine archaeology who had lived and worked in Lebanon.

Frost was then at her home in Marylebone but, “as the living memory of Lebanon before the war’’, could vividly recall details about the museum and its collection. “She guided us. She was an extraordinary woman, who really left her mark on my life. It was an immense privilege to have met her.’’

The end of the civil conflict in 1990 brought with it a new focus on Lebanon’s hidden ancient cities, and led to Doumet-Serhal holding Beirut: Uncovering the Past at the British Museum with its specialists Carole Mendleson and John Curtis.

From there, the trio’s collaboration continued in a search across the country for somewhere new to excavate, eventually settling on the layers of ancient city beneath modern Sidon largely ignored in earlier excavations by the Ottomans and French colonials.

Though the British Museum and the DGA funded the excavations for the first two years, Doumet-Serhal credits the Lebanese private and corporate donors who quickly became involved for supporting the project from then on.

Slowly winding down

As she speaks about the subsequent three decades that led to an MBE for services to archaeology, her undimmed excitement makes it difficult to believe that she means to walk away.

But in the annual Honor Frost Memorial lecture last year, she described the Sidon Excavation as “slowly winding down’’. Delving and discovering artefacts and skeletons, Doumet-Serhal explains, is only part of the work.

“The big responsibility when you dig, especially for 27 years, is to publish what you have found. If not, you better leave them where they are.

“Today, I must have a reason to continue without having published everything. I had a specific question that I needed to answer. Does that mean the archaeology of Sidon is over? No. It could be taken over by someone else one day.’’

The latest interruption

The site is currently covered in a protective sheet while a museum recounting the city’s history has yet to open. The war in Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah has become the latest interruption to the Sidon journey, after other disturbances including the assassination of prime minister Rafiq Al Hariri in 2005 and the carpet bombing by the Israelis a year later when the team was evacuated by the British Navy.

For now, she is finalising three volumes of documentation from her recent findings, and retains posts as a specialist assistant at the British Museum and honorary research fellow at University College London.

When asked what she does with any spare time, the conversation turns to sailing with her husband in Italy, sharing moments with their grandchildren, and making meals.

“I never cook quite the same thing twice because I love experimenting,” Doumet-Serhal says before quickly switching back to the all-consuming subject of Sidon where she will return as soon as the site reopens next summer.

“When I'm not digging, when I'm not in the field, I’m writing. Even if I'm not at my desk writing, I'm thinking all the time about the work I’m doing. It’s a hobby and a job at the same time. It eats you up,'' she insists. “It eats you up completely.”