Hayat was 15 when her father, through legal loopholes in Morocco's Family Code (Moudawana), bypassed the minimum marriage age of 18 and obtained court approval to marry her to a man 10 years her senior.

The mother of one filed for divorce two years later. Her husband was physically abusing, she said.

Hayat, now 25, is one of many women in Morocco whose underage marriage was enabled by articles 20 and 21 of the Family Code, which give state-appointed family affairs judges the power to authorise child marriages in certain circumstances.

“I dropped out of school at a young age and that is when my father decided I would marry a relative,” Hayat, who asked to be referred to by her first name only, told The National.

"I was a child then and didn't even know what marriage meant."

Moroccan child bride

Hayat was hoping for a good married life but found herself trapped, with a husband who mistreated her, she said.

“He treated me as if I was an adult capable of carrying tremendous responsibilities. I went from being 15 to being 26 years old. This was not the future I wanted. I was shocked with this new reality that just happened overnight."

Fourteen per cent of 20 to 24-year-old women in Morocco were first married or in a union before the age of 18, Unicef says.

Child marriages constituted 12 per cent of total marriage contracts between 2004 and 2019, dropping to just over 7 per cent in 2019, said recent data published by the Moroccan Public Prosecution.

In 2004, amendments to the Family Code increased the minimum legal age required for girls' marriage from 15 to 18, but according to data published by Civil Connections, a non-profit organisation that opposed the practice, 81 per cent of about 32,000 requests for child marriages filed in 2019 were approved by family courts.

Article 20 of the Family Code stipulates a family affairs judge may approve the marriage of a girl or boy below the legal age but must give well-substantiated justification. Meanwhile, Article 21 says a parent or guardian must give approval for a minor’s marriage and both the minor and the parent must sign a marriage authorisation request. The judge can either accept or reject it.

Amending these articles have become the key mission of civil societies and advocacy organisations, which have in recent years accelerated their efforts to combat the issue.

Aicha, 30, was married at 16 and divorced two years later due to her husband’s gambling addiction, she told The National.

When her family decided to marry her off, she was interviewed by the family affairs judge in the presence of her father.

“He asked if I was able to take on such a responsibility. I had no choice but to say 'yes', naturally. The whole family was waiting for the happy news to celebrate us as newly-weds,” she told The National.

“A year after our marriage, I discovered he was addicted to gambling. I told my mother but we kept it a secret between us.”

Detrimental factors

Socioeconomic and cultural issues such as poverty and widespread illiteracy were identified by Morocco’s Supreme Council of the Judicial Power as key factors leading to the prevalence of child marriage.

A number of initiatives are raising awareness among rural communities on the grave impact of child marriage on girls’ development, education and career prospects.

Project Soar, a Moroccan non-profit group founded in 2015, targets disadvantaged rural areas with the aim of ending the deep-rooted practice.

Building a Greater Girls’ Movement (Bigger) initiative, launched in 2022 by Project Soar in partnership with 18 other organisations, also aims to close legal loopholes by 2025.

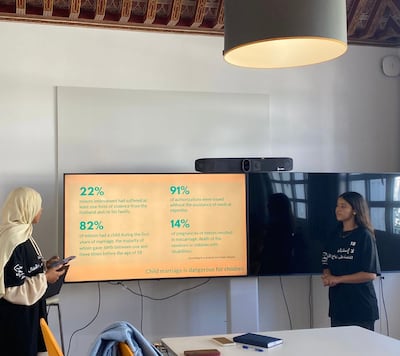

Tens of teenage graduates from Soar’s empowerment programmes are now leading Bigger's efforts to equip girls with legal and advocacy knowledge to engage with policymakers, including parliamentarians and ministers, to discuss modifications to the Family Code.

Project Soar team up with Morocco’s Ministry of Solidarity and Social Integration in October to combat child marriage.

Turning girls into advocates

Kaoutar Arhenbo, one of Bigger’s facilitators, told The National girls taking part need to complete an eight-month “multifaceted empowerment programme" which includes focused workshops to reinforce confidence and develop leadership skills.

Since it’s launch, 20 of Bigger’s alumni have trained and mobilised many teenage girls to help them challenge child marriage in their communities.

They have also held talks with parents, youths, local officials and stakeholders to raise awareness of the negative impact of child marriage, Miss Arhenbo said.

The Mobilising for Rights Associates (MRA), a Rabat-based organisation of legal experts and one of Bigger’s main partners, "drafted a proposal to amend the articles associated with child marriage, and arm the girls with a wide number of documents before going to Rabat to meet the officials”, MRA president Saeeda Kozi told The National, referring to Bigger girls recently attending parliamentary debates to propose amendments to articles of the Family Code.

Impact and limitations

Nour el Houda, 15, came across the programme from a family friend whose daughters were also participants.

“I didn’t know what to expect but as I attended more sessions I began to understand more about child marriage and self-confidence,” she told The National.

She was a member of the delegation that attended November’s parliamentary deliberations and the programme was life-changing, she said.

“The empowerment workshop altered the way I think of marriage for girls my age.

“I use every opportunity to pass on what I have learnt on the rights guaranteed by law to girls our age."

But according to another Soar facilitator, Ferdaous Atbib, some parents resist enrolling their daughters. “We do house-to-house visits to explain to the parents the positive impact of the programme on their daughters’ futures,” she said.

However, legal experts say efforts to amend the Family Code must work in parallel with real economic and educational development in rural areas.

“Young girls in rural areas must be empowered economically and through providing access to education, in order to combat deep-rooted social norms regarding child marriage,” Abdel-Ilah El Khedri, president of the Moroccan Centre for Human Rights, told The National.

“Today more than ever, it is necessary for those in charge to take collaborative measures that can consolidate the chances of minor girls to succeed in their lives, by providing ways to protect them, and develop their skills until they are adults."

This article is published in collaboration with Egab