Shortly before Gareth Smyth left Beirut to head the Financial Times bureau in Tehran in 2003, he swung by the home of Rafik Hariri, Lebanon’s prime minister, to ask him about the move.

"In Beirut it takes only minutes and you know what is going on in the whole world," Hariri told the British-Irish journalist. "In Tehran you can live for decades and you cannot even know what is going on in your own street."

But Smyth, who died on January 15, aged 64, took the job in Tehran, adding the country to his portfolio of deeply reported journalism on everything from the music of Lebanese oud maestro Rabih Abou Khalil to the intricacies of Kurdish politics.

Jim Muir, the BBC’s Middle East correspondent, with whom Smyth shared an office in Tehran, said the reporter was “a staunch and wryly funny friend, as well as a journalist of insight and integrity”.

In 2005 he interviewed Iranian dissident Saeed Hajjarian. Known as the “brain of reformists,” Hajjarian was shot point-blank in the face in 2000, leaving him paralysed.

His attacker was jailed for just two years.

“I found him an engaging rather than a miserable man, sanguine about Iran’s prospects under [Iranian president Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad but just as eager to express his love of poetry and music,” Smyth later recalled.

Smyth cut his teeth in British journalism, writing for the New Statesman, The Scotsman and other publications. He once went to interview the Irish Republican Army commander Martin McGuinness who took Smyth fishing on the condition that the journalist did not reveal the location. A picture Smyth took of McGuinness holding a big fish hung in his Beirut apartment. Nearby was a photograph of Smyth’s Welsh mother Hilda, who died of cancer when he was 11. His father, Matthew, was Irish, from County Monaghan.

These Irish roots helped him bond with Iraqi-Kurdish guerrilla commanders, who now control the north of the country, as well as peaceful members of the Kurdish national movement in Iran, underdogs in a struggle for self-determination.

Among them was Iranian-Kurdish opposition leader Sadegh Sharafkandi, who was assassinated in Berlin with two other dissidents in 1992.

The killings, carried out by Iranian agents and Hezbollah operatives was named Operation Mykonos.

“Sharafkandi was just a lovely man,” Smyth once recalled, tearing up.

In 1996 Lebanese publisher Jamil Mrowa hired Smyth as a member of a veteran British team to relaunch The Daily Star in Beirut. The newspaper was started by Mr Mroueh’s father, the assassinated journalist Kamel Mroueh.

In Beirut, Smyth lived above Le Chef, one of the last old, family owned restaurants in the city. He ordered meat hummus with almost every meal, and calculated that it was cheaper to eat at Le Chef every day than to shop for ingredients.

Smyth graduated in politics, philosophy and economics from Queen's Church, Oxford, and was active in the Labour Party before becoming a journalist.

He had an acute understanding of political theory – of the brutal school of politics in his Irish fatherland and of the Middle East.

He covered the Israeli withdrawal from south Lebanon, the death of Syrian president Hafez Al Assad and the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, when a car he was in overturned three times.

In the past decade he ghost-wrote the biography of Kuwaiti businessman Saad Al Barrak, who pioneered the mobile phone industry in the Middle East. Smyth also wrote for The Guardian, mainly on Iran.

He also contributed to other publications, including The National, where he mainly wrote pieces on literature.

Before he died, Smyth was about to finish another book he was writing in collaboration with prominent Lebanese law professor Chibli Mallat. This was to be on the humanist thought of Musa Al Sadr, the "vanished imam" who disappeared in Libya after a meeting with Muammar Qaddafi in 1978.

Smyth was a highly skilled and talented photographer. He was also a keen hiker who enjoyed taking his guests on tours of Iran, where they did lots of walking.

While asking for directions on a hike at a park in central Iran in 2007, Smyth was arrested on the grounds that foreign journalists needed permission to be there.

The British embassy in Tehran got him out after a four-day incarceration, in what he described as a "dry run" for negotiations the mission conducted following the arrest a few weeks later of 15 British Royal Navy personnel in waters separating Iraq from Iran.

Later, over lunch, an Iranian official asked Smyth if he was having any difficulty covering the country. He replied that nothing immediately came to mind.

His detention was not lost on the Iranian official, and Smyth was not sure whether the man was sending him an assuring message, a threat or both.

But he knew that to operate in Iran, subtlety had to be the mark of any good reporter.

Two weeks ago, Smyth was walking near his home in County Mayo on the west coast of Ireland when he suffered an apparent heart attack and died immediately, according to a friend who was with him.

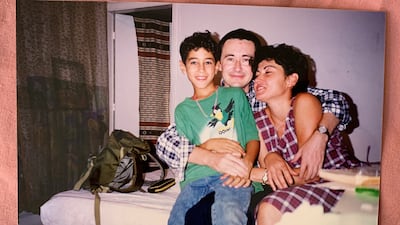

Smyth is survived by three brothers, and his partner, the Lebanese journalist Zeinab Charafeddine, plus her son Nader Diab, a lawyer and senior policy officer at at an international charity in London.