Radical Islamists loyal to the regime of ousted dictator Omar Al Bashir are making a political comeback after three years of post-revolution disenfranchisement, Sudanese activists and analysts say.

They say the radicals — who have been been sidelined since the dictator was removed, are gaining key government positions.

Their return poses a threat to chances of a resolution to the political crisis pitting the ruling military against the pro-democracy movement responsible for the expulsion of Al Bashir’s loyalists, the analysts say.

Their return is reversing the dismantling of the former dictator’s “deep state” after he was deposed in 2019.

It also rises fears of a power grab by Al Bashir loyalists in collusion with army officers who share their ideology and are opposed to the idea of the relatively liberal and secular-leaning pro-democracy movement rising to power in the mostly Muslim and conservative Afro-Arab nation.

“The old Al Bashir regime is a stone’s throw away from power,” said Amani El Taweel, one of Egypt’s best informed experts on Sudan, in a recent Facebook post, underling the gravity of the political situation in Sudan.

A return to power by Al Bashir Islamists in any disguise would have serious ramifications in Sudan and beyond, deepening the country’s isolation and leading major regional powerhouses such as Egypt to keep Khartoum at arm’s length.

Already, Sudan is being denied billions of dollars’ worth of western aid and debt forgiveness in response to the military’s seizure of power in a coup last October that derailed the country’s transition to democratic rule and plunged it into its worst economic downturn in living memory.

The return of Al Bashir’s loyalists has been made possible by court rulings issued by sympathetic judges and by the desire of the military to use former regime loyalists to counter the popular appeal of the pro-democracy movement, the activists and analysts say.

The Islamists, who helped Al Bashir to create a corrupt and radical state that was an international pariah for most of his 29-year rule, have made their comeback chiefly in the judiciary, state media, foreign service, education and the civil service.

Separate court rulings have also freed significant assets belonging to stalwarts of Al Bashir’s now-banned Islamic Conference party and their business associates. There have also been verdicts lifting the ban on major non-governmental organisations loyal to the former president.

The assertion that the Islamists have made a comeback was borne out by UN special envoy to Sudan Volker Perthes when he addressed the UN Security Council on September 13.

“Elements of the former regime which were displaced by the revolution are gradually returning to the political scene, to the administration, and to the public space,” he said, but gave no details of the extent of their comeback nor its possible political impact.

“The military had no choice but to look for a civilian power base. The return of Al Bashir loyalists to fulfil that role was just a matter of time. It was the plan from day one,” said political analyst Iman Fadl.

“The chances of their return to power grow if the pro-democracy movement does not close ranks and reach a deal with the military.”

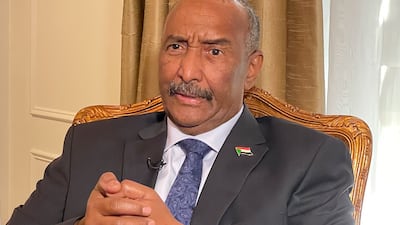

General Al Burhan's growing power

Led by army chief Gen Abdel Fattah Al Burhan, last year’s military coup terminated an uneasy partnership between the generals who removed Al Bashir in April 2019 and a pro-democracy movement that engineered months of street protests in late 2018 and early 2019 against his divisive rule.

The pro-democracy movement has led opposition to the coup, organising mass street rallies to demand that the generals step down and leave politics altogether. Their campaign has been met with deadly force by security forces, who have killed at least 117 protesters and injured 6,000 since October.

The return of the Islamists, according to the activists and analysts, has been allowed to proceed quietly and gradually to shield the ruling generals from charges of reinventing the old regime.

Already, the generals have allied themselves with former rebel leaders with whom they signed a peace deal in 2020. However, the rebel leaders have been shown to wield little sway in their home areas in western Sudan and to have little or no appeal outside those areas.

Betraying their desire to get the Islamists back and on their side, Gen Al Burhan and his associates have repeatedly saved their harshest criticism for a defunct commission mandated by the transitional administration with dismantling the “deep state” put in place by Al Bashir.

Significantly, the decision to suspend the commission was included in Gen Al Burhan’s televised broadcast announcing the power grab on October 25. Key members of the commission have been detained for weeks, sometimes months, since the coup.

Gen Al Burhan and his top associates contend the commission has exceeded its mandate and its members were motivated by their own personal interests.

“We are almost back to where we were before the revolution,” said Sudanese political analyst, Omar Barakat.

“They (The Islamists) have returned to power and are now preparing themselves to rule again,” said political activist Mohammed Al Sayed. “They have done all this through and with the help of the military regime.”

Since the coup the military has repeatedly pledged to step down, but only on condition they hand over power to an elected government, in effect ruling out a civilian-led, transitional government running the country until elections are held.

The generals suggested that civilians would be left to select the head of state and prime minister, but are on record saying that the military would retain the final say in politics while categorically ruling out any civilian oversight over the armed forces, police, security forces and intelligence agencies.

Civilian oversight is among the key demands of the pro-democracy movement, who view it as essential to the establishment of an enduring democratic system.

Gen Al Burhan, meanwhile, has been cementing his position as the country's head of state, stoking suspicions by many of his critics that he has no intention to relinquish power.

The general represented Sudan at the funeral last week of Queen Elizabeth II, addressed the UN General Assembly and met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi in Cairo over the weekend during a stopover on his way home from New York.