The Middle East is one of the most vulnerable regions when it comes to climate change.

US military satellite imagery from the 1960s and 1970s from the declassified Corona reconnaissance programme starkly illustrates this challenge, showing a landscape that has changed a great deal over the decades.

A 2019 study by the World Resources Institute showed that 12 of the 17 most “water stressed” countries in the world are in the region.

In particular, the images highlight demographic pressure — defined by the Fragile States Index, a conflict monitor, as “pressures upon the state deriving from the population itself or the environment around it”.

Some of these countries — including Yemen, Syria and Iraq — are experiencing water scarcity, climate change, conflict and mismanagement, which combined create a multi-sided crisis, worsening the impact of drought and desertification.

Rapidly growing populations have compounded the problem — even countries that have not been directly affected by war such as Jordan and Saudi Arabia face a challenge to maintain water security.

Images from the US Centre for Advanced Spatial Technologies show the many changes in the region since the 1970s, when the Middle East’s population was estimated to be about 120 million.

The World Bank estimates the region's population rose to more than 420 million in 2020 and could cross 700 million by 2050 if current demographic trends continue.

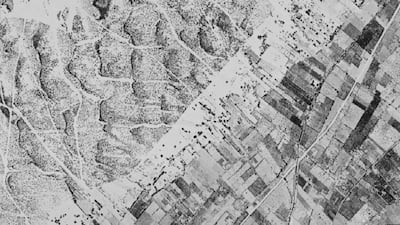

Comparing the Corona programme imagery with recent satellite images shows the changes in land use during this demographic boom.

In a 1969 image of Buraydah, Saudi Arabia, the Prince Naif bin Abdulaziz International Airport, built in 1964, is barely visible in the centre of the photo. Along with roads, it is the only recognisable feature of a landscape now transformed by new villages, a university and the distinctive circular fields of centre-pivot irrigation.

Images of such development emerging in arid environments point to coming challenges to national water strategies and show what is at stake for these communities facing a future of reduced water supplies.

In the case of Iraq and Jordan, national strategies call for repairing leaking and ageing water infrastructure, investing in more efficient irrigation methods, rationing groundwater and enacting a tariff programme to encourage water saving.

Harsh recent droughts as well as pressure to raise agricultural production amid the food crisis sparked by the Ukraine war have given urgency to these plans.

Jawad Al Bakri, an agriculture professor at the University of Jordan, says a large reduction in water quotas for farmers will affect yields significantly this year, on top of generally bad harvests in 2021.

He suggests that the government should grant groundwater licences in the northern Jordan Valley, one of the country’s main farming regions. Jordan receives more than half of its water from underground aquifers, but some experts fear they are dangerously depleted.

Mr Al Bakri believes there is little choice.

“Some wells must be drilled to compensate for the water deficit,” he told The National.

To alleviate the competition for water between the agriculture, domestic and industrial sectors, focus has moved to recycling wastewater and repairing or replacing old and leaking infrastructure.

From the Jordanian government side, a plan to jump-start the economy unveiled this month said agricultural production consumes half of the water resources in the kingdom while contributing 5 per cent to GDP and 6 per cent to exports.

The plan did not go into specifics, unlike a recent master plan to overhaul farming in Jordan devised by the German Corporation for International Co-operation, which reduces the size of irrigated areas while increasing yields.

For cities such as Zarqa in one of Jordan's poorest governorates, the struggle will be to reduce groundwater use, a report published last year by the US Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed.

The EU last year announced that the Zarqa-Amman area would receive €60 million ($63m) in grants and loans to build a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant.

That would be in addition to a nearly $300m project funded by the US aid agency Millennium Challenge Corporation to improve water treatment and efficiency in Zarqa, completed over five years in 2016.

Time is a luxury however — the study said Jordan “must enact an ambitious portfolio of interventions that span supply- and demand-side measures” as soon as possible.

Expanding cities

Satellite images show urban sprawl taking over large parts of the desert and farmland, as seen in Samawa, southern Iraq — one of Iraq’s most water-stressed cities, and Zarqa, a governorate whose population has swelled as generations of Palestinian refugees from the Arab-Israeli conflict settled in its largest city.

50 years of change in Zarqa, Jordan

A comparison of Gaza following the 1967 war and today shows vast areas of rolling sand dunes becoming agricultural land and the expanding city of Khan Younis — all dependent on an aquifer, the strip’s main source of water.

Now there are fears that the desert will reclaim these irrigated areas, turning the heavily populated area into a dust bowl.

Gaza has some seawater desalination plants that provide drinking water for about 70,000 of the two million residents and the World Bank plans a much larger facility that will provide water for more than 800,000 people.

But desalination is energy intensive, raising the question of how sustainable it would be in a territory that struggles to produce enough power.

Gaza's parched future

In addition to climate-related challenges, Gaza has been under Israeli blockade for 15 years, sometimes described as the world’s largest “open air prison."

The densely populated strip of land also suffers from a severe fuel shortage due to Israel’s blockade and a high daily demand of power.

“Gaza suffers from reduced rainfall, annual seawater level rises and more extreme heat events already as a result of climate change,” Amira Aker, a postdoctoral fellow at Canada’s Universite Laval, told The National.

“Hundreds of years ago, Gaza was considered an oasis due to the abundance of water it had.

“Today, its aquifers are over-drafted, and its sea contaminated with sewage waste which seeps into the fresh water supplies.

“Combine those factors with Israel’s uprooting of trees along its border with Gaza, which causes the soil to lose organic material and contain less roots with which to hold on to water, contributing to desertification.”

Less rain has also motivated farmers to use more chemicals to get higher yields from their crops.

“This also leads to problems in the soil like soil degradation and loss of biodiversity,” Ms Aker said.

50 years of change in Khan Younis, Gaza

Iraq on the brink

Like much of Iraq, Samawa has struggled to sustain crumbling water infrastructure. Households compete for water with agriculture — local authorities say 1,000 illegal wells have been dug for farming during a recent period of drought — and industry.

Compounding this problem, upriver dam construction on the Euphrates River and a succession of severe droughts has reduced available water over the decades, leading to rising salinity in the river — the town's main source of freshwater.

Water flows in Iraq's two biggest rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, have dropped by about two thirds since major dam projects in Turkey, Syria and Iran began in the 1970s.

At the same time, Samawa has expanded rapidly.

50 years of change in Samawa, Iraq

Authorities blame illegal wells and overuse of water by cement plants and salt factories for the drying up of a lake near the town, Lake Sawa, which had been a tourist destination as recently as the 1990s.

During the 1990s, the population of the province where Samawa is located, Al Muthanna, swelled due to an influx of refugees following an uprising against Saddam Hussein in 1991.

At the same time, Iraq's rapidly growing population was placing increasing pressure on vital services that were failing due to international sanctions.

Samawa has relied on World Bank assistance to launch a series of water projects since around 2010. One of them is near completion but was delayed due to a lack of Iraqi government funds during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Further south, the port city of Basra faces equally severe pressure. In 2018, amid a severe drought, a combination of rising seawater encroaching into the city's dwindling freshwater supply and pollution from several sources sickened more than 100,000 people.

Unlike Samawa, Basra can benefit from large-scale desalination plants, but such projects take years to complete and are often delayed by Iraq's pervasive political corruption.

“Iraq is currently in its summer months, which means the recurrent events in Basra are renewed, namely the extension of the 'salt tongue' from the Arabian Gulf into the Shatt Al Arab, and then to the city of Basra, which causes desalination plants installed on it to stop,” said Zainab Mehdi, a Women and Security Fellow at the Cambridge Middle East and North Africa Forum.

“The future government should find solutions to this, such as the construction of a moveable dam on the Shatt Al Arab, as well as the installation of desalination plants for extremely saline water.”

As with Jordan and Gaza, time is not on Iraq's side: the country's population, now 41 million, is projected to reach 50 million in 2030.