It is match night and many in this Nile Delta village are rushing on narrow, dusty streets to do last-minute errands and shopping before the 9pm kickoff.

Soon after the day’s final call to prayer rings out from Nagrig’s 15 mosques, the streets begin to slowly empty, while the village’s cafes and tea houses start to fill.

Hundreds take their seats in front of giant TV screens.

They order tea, coffee and cold drinks and begin to watch native son and Liverpool star Mohamed Salah ply his trade once more, this time in an Egypt jersey.

Salah’s rise to stardom since joining Liverpool four years ago has redefined this village north of Cairo where he was born and raised.

The love and respect that his footballing skills have earned him here can be found elsewhere across Egypt.

But in Nagrig – population 15,000 – the Salah phenomenon goes beyond admiration for the winger's dazzling dribbling, deadly left-footed shot or even his global fame.

It’s much deeper and more impactful.

A nation of more than 100 million people, Egypt never had one of its own who has captivated and inspired the way Salah has since joining Liverpool. Besides the late leader Gamal Abdel Nasser and singer Umm Kulthum, no one even comes close.

In the years since he first left Egypt to join Swiss club Basel in 2012, Salah has poured millions into services and good causes in Nagrig, the nearest town and beyond. The list of beneficiaries of his multi-million-pound benevolence is wide and diverse. It includes widows, orphans, the elderly, cancer patients, schoolchildren and Syrian refugees.

Such generosity has added significantly to the aura around the player.

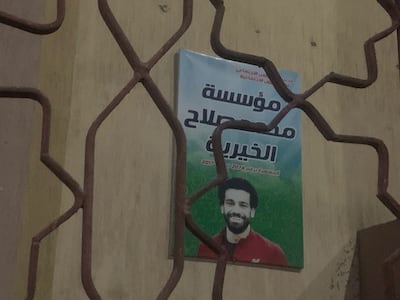

“We can only pray that God makes Salah wealthier and wealthier,” says Hassan Bakr, chairman of the player's Mohamed Salah Charity Foundation.

He is commenting on speculation in the British media that Salah's representatives are seeking a weekly salary of anywhere between £300,000 ($412,000) and £400,000 for the player, up from £200,000 under his current contract that expires in June 2023.

Mr Bakr and the village mayor, Maher Shtayyeh, said the foundation gives out 60,000 Egyptian pounds ($3,800) in monthly stipends to poor widows, divorced women, orphans and the elderly. It also gives out monthly stipends of up to 400 Egyptian pounds to poor Syrian refugees.

The foundation also gave the village its first ambulance and built a primary and middle school at the cost of 17 million Egyptian pounds. The school is run by and follows the curriculum of the centuries-old, Cairo-based Al Azhar, the world’s primary seat of learning for Sunni Muslims.

The foundation also donated 54 million Egyptian pounds to Cairo’s main cancer hospital after an explosion on the street outside it killed 20 people and damaged the centre in 2019, the mayor and Mr Bakr say. It has also spent millions upgrading the general hospital in the nearby town of Bassioun, which serves Nagrig, providing it with equipment and overhauling its sewage system.

In 2016, Salah donated five million Egyptian pounds to the Long Live Egypt Fund, which finances development projects and is personally managed by President Abdel Fattah El Sisi.

Mohammed Al Saadany, 37, the owner of a home appliances store in Nagrig, says everyone waits eagerly for Salah's matches.

“It is not just about football," says Mr Al Saadany, while sitting below a TV airing a recital of Quranic verses.

"His good reputation precedes his stardom. He can do no wrong and nothing came easy to him.”

“I get a peculiar feeling when I see a match featuring one of our very own, who has gone so far. I was never too keen on football, but I don’t miss any of his matches now.”

A father of four, Mr Al Saadany settled back in Nagrig in 2017 – after a decade working as an accountant in Saudi Arabia.

Like others in the village, Mr Al Saadany frames in religious terms the wealth acquired by Salah as a footballer and from commercial endorsements.

He credits a love of God as the source of everything good that has come the player's way.

In some ways, not begrudging Salah his fortune is a noble sentiment in a country where many live in poverty or at least struggle daily to make ends meet in the face of rising prices and limited opportunities.

“We never gave a fleeting thought to how much he makes. He is now negotiating a new contract with a higher salary, right? Messi and Ronaldo are making this much or even more, so why not Salah?” Mr Al Saadany says before citing a verse from the Quran that, in paraphrase, says God, the Prophet Mohammed and the faithful take note of whose who labour.

Mohammed Mustafa, 45, an employee of Al Azhar who also works as a tailor in the evenings, declares himself disinterested in football. But, as a Nagrig resident, he says he is fully aware of Salah's effect on the village.

“The change Salah brought to this village is that all the kids now want to play football and everyone wants to be as successful as he is,” he says from behind a sewing machine as he alters a pink dress.

“We never dreamt that we would give the world someone like Salah. So, when God gave us Salah, we thought it was a divine blessing,” says Mr Shtayyeh.

Life in Nagrig has continued largely unchanged since Salah's rise to stardom, he says, with growing of jasmine for the cosmetics industry and trading in onions being the main sources of income.

“One change is that the village has become a magnet for journalists from around the world as well as people who need money and think they can get it here.”

Indeed, on the evening of October 11 as Egypt take on Libya in a World Cup qualifier in the city of Benghazi, Nagrig appears like a typical Egyptian village.

Motorcycles, horse-drawn carts and tuk-tuks dart through the streets lit by dim lights and a bright crescent moon rising up in the clear night sky. Accompanied by their owners, water buffaloes make their way home after a day's grazing in fields outside the village.

And, curiously, a young donkey is protesting angrily as it tries to keep up with the motorbike it is tied to on the way home.

Schoolchildren carrying shoulder bags walk home lazily after private classes, while mothers wait in bakeries to buy bread for the sandwiches their children will take to school the next day.

But amid all the hustle and bustle on the rubbish-strewn streets – which also have their fair share of animal droppings – Salah is never far away.

Stickers depicting the player in adverts for mobile phones can be found on the windows of some shops. A mural of Salah adorns the walls of the school he built, next to motivational phrases typically found in schools across Egypt, such as “praying is the backbone of the faith”, “reading builds minds and gives joy to the soul” and “a drop of water equals a life”.

A short distance away is a mural of Dr Ahmed Al Tayeb, Grand Imam of Al Azhar.

The walls of most cafes in the village are plastered with images of Salah. In a cafe called El Alamy – Arabic for "the international" – and owned by a Salah cousin, patrons sit on chairs arranged in rows to watch the Egypt-Libya match.

Salah does not score – stretching his goalless run for the Pharaohs to three matches – but Egypt go home with a convincing 3-0 win that greatly bolsters their chances of qualifying for the 2022 World Cup.

The 50 people in the cafe sip beverages and cheer wildly when Egypt score or come close. Everyone is a little disappointed that Salah does not convert the handful of chances he has, but the win for Egypt and the prospect of playing in Qatar next year makes everyone happy.

The excitement is palpable and, while everyone has nothing but football and Salah on their mind, university student Abdel Rahman Nasr, 18, says that success, even in Nagrig, should never be just about football.

“Everyone wants to be a star like him, but I want to be a star in my field. My dream is to influence society. I want to be successful first, then I will think of money,” says the first-year business student.