There’s widespread jubilation among the supporters of Morocco’s liberal party National Rally of Independents (RNI) that the future is with them as long-ruling Islamists have suffered a crushing defeat in the parliamentary elections on Wednesday, according to provisional results.

After 10 years of successive governments dominated by the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD), the RNI's popularity was already riding high in the months leading up to the vote, analysts told The National, offering the best insight into the race because election polls are banned in the kingdom.

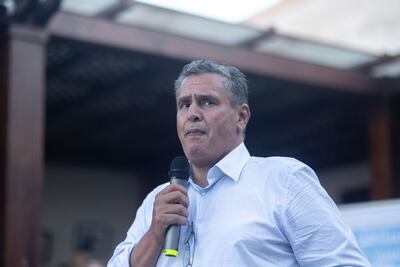

RNI's head Aziz Akhannouch led the party to take 97 seats out of 395, after 96 per cent of the votes were counted. As for the PJD, which has headed governments for a decade since 2011, it suffered a complete rout as its share nosedived from 125 seats in the outgoing parliament to just 12.

The RNI leaders said during campaigning that it is high time they led the next government to make much-needed changes and improve education, health care, employment and welfare in the country.

The PJD has been singled out for sharp criticism by economists and political scientists for failing to galvanise the economy, which shrank by 6 per cent last year, as well as for being unable to tackle corruption and improve living conditions for the majority of the country’s 37 million people.

“The general mood, especially among the swing and angry voters, was 'let’s end the reign of the PJD and try our economic chances with other well-established and pro-king parties like the RNI,' which is led by business tycoon Aziz Akhannouch,” said Mohamed Bouden, head of the Rabat-based Atlas Centre for the Analysis of Political and Institutional Indicators.

“The PJD didn't have a big economic or social achievement it can count on as a rallying point in this election,” he told The National.

Morocco is a constitutional monarchy. The king picks the prime minister from the party that wins most seats in parliament.

King Mohammed VI has unveiled a 15-year development plan to help bridge economic inequality and boost job creation.

“That also endeared voters to the leaders of the pro-palace parties,” Mr Bouden said.

'You deserve better'

The RNI has used the slogan “you deserve better” during its campaigns.

Founded in 1978 by Ahmed Osman – prime minister at the time and the son-in-law of King Hassan II who ruled the country between 1961 and 1999 – the party has participated in several Moroccan governments since the 1970s.

After unrest broke out across the Arab world in 2011 the RNI re-emerged as a political force in Morocco, with Mr Akhannouch becoming its president in 2016.

Mr Akhannouch, who has been the Minister of Agriculture since 2007, believes that his party has developed a clear and feasible programme based on travelling widely in the country to speak to voters from different walks of life.

Earlier this year the tycoon launched the 100 Days 100 Cities programme, which he considered to be the best-funded and most ambitious public consultation in Morocco's history.

Mr Akhannouch has promised to increase the monthly salary of teachers, create one million jobs and allocate a monthly salary for those of 65 years and above without an income.

“The citizens' demands revolve around social welfare, the doubling of the health sector's budget as well as the achievement of quality education,” he said in a recent interview with Moroccan media.

In the October 2016 legislative elections, his party won just 37 seats.

“The RNI has deep pockets and no party can match the wealth of its leader and his well-funded publicity drive in TV, street billboards or social media. It’s widely known here in Morocco as the party of businessmen. It’s like a money machine and the growing public frustration at the Islamists plays well into their hands,” Saida El Kamel, a political science researcher at the Mohammed V University, told The National.

Mr Akhannouch is one of the richest people in the Arab world, with a net wealth of nearly $1.8 billion, according to Forbes. He runs a business empire that includes about 50 companies, mainly in the fields of energy and communications.

The father of three was born in Tafraout, southern Morocco, in 1961 and studied administrative management at the prestigious Canadian Universite de Sherbrooke in 1986.

But experts say his party’s big gains in the elections are also linked to the failure of Islamists in other Arab countries to consolidate their power base, such as Ennhada in neighbouring Tunisia and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

They have proved out of touch, says Mustafa Menshawy, a post-doctoral fellow at Lancaster University’s sectarianism, proxies and de-sectarianisation project.

He explained: “I believe that the main problem with Islamists in power revolves around a struggle to juggle religion and politics. With the first mostly fixed and immobile and textually sacred, and the second dynamic, shifting, malleable and profane, the Islamists’ rise to power thus exemplifies a moment of tension, incongruity and contradiction between the two paths,” he told The National.

“Members of the parties and many people felt disillusioned as Islamists always propagated their preparedness for a radical full 'overturn' or transformation of power by replacing an old regime with a puritan one, bringing the dream of 'Islamic state and society' closer," he said. "It was more a baptism by fire under which they enter this upper level of politics through immersion and without full preparation.”