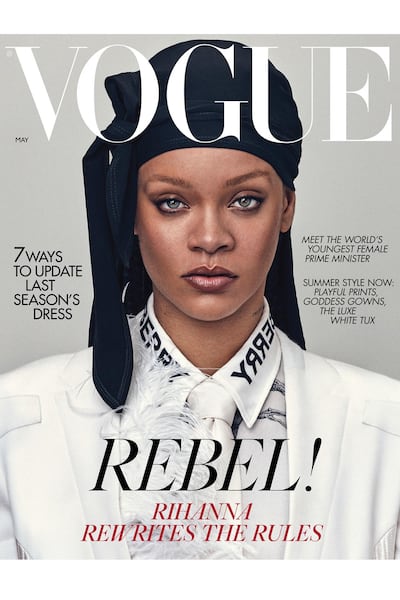

Anyone of colour will probably already know what a durag is, while the rest of us will have seen them worn in most major cities and in pretty much any rap video ever made. Now, singer Rihanna has worn one on the cover of the May issue of British Vogue and suddenly, the durag is big news.

Also called a du-rag or do-rag, it is essentially a piece of cloth that ties around the head, yet this simple construction belies several connotations.

Although the origins are hazy (as The New York Times quipped, it is like "asking who invented the comb") it has links to the transatlantic slave trade and race-based poverty dating back more than 200 years.

There are conflicting views as to whether enslaved women were forced to wear the cloths as a marker of low status, or self-adopted it for protection against the weather. Whichever is true (possibly both), the stigma around wearing one was so great that not until the so-called Harlem Renaissance of the 1920-1930s and the boom in African-American arts and culture did using one become acceptable again, when to maintain the fashionable hairstyles of the day a durag became a necessity, to hold hair that had been laboriously brushed out, flat.

The Black Power Movement of the 1960s resulted in another resurgence of cultural pride, and brought the durag from the privacy of home, and protecting wave hairstyles, out into the public domain where it became a symbol of reclaimed identity. The arrival of the burgeoning hip-hop music scene of the 1980s and 1990s quickly adopted the durag, often wearing it under baseball caps, and soon any rapper of note sported one. It became so synonymous with the genre that even (Caucasian) rapper Eminem wore one to collect his 2003 Grammy Award, while Jay Z and 50 Cent preferred to wear theirs with suits.

However, the link with American rap began to segue into a link with US gang culture. It became so intertwined that when actor Denzel Washington played corrupt police officer Alonzo Harris in the 2001 film Training Day, he wore a durag to highlight his character's nefarious nature.

Even as recently as 2019, US schools were attempting to ban students from wearing them, prompting mass walkouts in protest. Although excruciating (and ill-advised) appropriation by the likes of Hulk Hogan (on The Arsenio Hall Show in 1989), Steven Seagal in the film Half Past Dead in 2002, and John Travolta promoting the 2007 film Wild Hogs, the durag is still weighed down with such stigma and negative association, that wearing one has once again become a statement of disruption, to come full circle.

Case in point, always-looking-to-question-boundaries Rihanna arrived at the 2014 Grammys wearing a barely there crystal dress by Adam Selman and a matching durag. When she performed at the VMA Awards in 2016, she chose a fishnet durag that hung down her back, and for her Fenty x Puma collection, in spring / summer 2017, many of her models wore durags, too.

When Beyonce and Jay Z closed the Louvre in Paris to film the video for the song Ape**** in 2018, it is no coincidence that one scene features dancers clad in white, floor-length durags. Beyonce's sister, Solange, meanwhile, arrived at the Heavenly Bodies 2018 Met Gala clad in Iris Van Herpen and a black durag, worn under a braided halo, the hem of which read, "My god wears a durag".

Now, for the May issue of British Vogue, Rihanna has made history by wearing a durag on the cover for the first time in the magazine's 104-year history. The imagery, created in collaboration with editor-in-chief Edward Enninful, is a powerful statement on many levels.

It is another fearless step by Enninful, who since taking over in 2017 has remade Vogue into a champion of inclusivity, pivoting it away from its white-bastion past. It is Rihanna reinventing herself once more, now as an androgynous, suit-clad figure, with her famous tresses covered in a durag and the word truth painted on her face. It is, in the words of contributing editor Funmi Fetto, a reclamation of "the head cloth birthed in oppression, [as] a celebration of black culture".

Of course, in the present moment, distracted as we are with fears of Covid-19, the timing of this is immaculate. As we start to rethink our lifestyles while in isolation, that Rihanna – a bold and tenacious young woman – should challenge norms by wearing head gear associated with gangs and violence is fitting. That she chose to do so on the cover of one of the world's most influential titles could not be more welcome. Nor can it be a surprise that the image is flanked by a headline that reads "7 ways to update last season's dress".

As we teeter on the edge of what could well prove to be pivotal shift away from blind consumerism, towards something slower and more sustainable, how apt that British Vogue and Rihanna have joined forces to show us that the way ahead is by learning from the past.