Within an hour of her first meeting with her future husband, Amey Sarode, in 2018, Bhavana Patil told him that she stammers. “He was a bit surprised as we had only chatted in Marathi until then, and I do not stammer when I speak Marathi,” says Patil, 29.

She directed him to some blog posts about her experiences with stammering. "Read my posts and let me know if you still want to meet again," she told him.

“I can’t imagine what you went through,” Sarode told Patil when he met her next. “But I can assure you that your stammer would never become a hurdle in our relationship.”

While Sarode's empathetic reaction is a major reason why the duo have been happily married for two years, Patil says: "That confidence to tell a prospective [arranged marriage] partner that he should accept my stammer before we proceed is something I got from Tisa."

The Indian Stammering Association

Patil chanced upon The Indian Stammering Association online in 2016, when she was dejected, unable to find a suitable job after her engineering degree, and “as usual” holding her stammer responsible for her problems. “I emailed them looking for a solution for my speech, but what I got was life-changing.”

Tisa – the largest community in India for people who stammer – offers free online courses, counselling, communication workshops and daily virtual meetings for its 4,000-plus members. City-specific self-help groups offer tips and techniques to manage stuttering, plus mental and emotional support.

The stigma of stammering

More than 70 million people worldwide stutter and, while it is recognised as a disability in the UK and the US, India does not list it under its Rights of Persons With Disabilities Act, thereby limiting its awareness as a social problem for people who live with it.

Most Tisa members grew up with the same experiences: unable to respond to the roll call in school; bullied by peers; not performing well in oral exams and project presentations; and limited social interactions.

Stammering is also a stigma in the country, especially for women.

The pressure of being a “perfect woman” in order to be eligible for marriage is too high, Patil says. It’s why her worried mother asked her to hide her stammer from potential grooms. “There is immense resentment in people for their daughter-in-law when she doesn’t measure up to their expectations,” Patil says, offering an insight into India’s as-yet gender disparate society.

Prathibha Ramamurthy, 32, a senior presales consultant in Bengaluru, got the same advice from her mother. “At one point, my family suggested I marry my cousin, since it may be difficult for me to meet a partner with my stammer.”

While consanguineous marriages are permitted in her community, Ramamurthy refused. She found a partner who accepted her despite his parents’ and siblings’ unfavourable attitude, which still exists in the form of mockery. “It isn’t easy, but my husband’s love keeps me going,” Ramamurthy says.

Others, such as chemical engineer Rajgauri Vedprakash, 23, experienced depression. "I worked so much harder for my college projects, but experienced a block while presenting and sometimes couldn't speak at all. For a long time, I had very low self-esteem."

Self-acceptance is paramount

Ramamurthy attended Tisa's weekly self-help meetings for three years, where she practised techniques to improve her fluency. Meditation and counselling by a peer group helped boost her confidence and, in time, she accepted her stutter as a part of herself. "All my life I had lived in denial, and blamed my parents and God for giving my stammer to me," she says.

Fellow Tisa member Anupam Saxena, 32, even started a theatre group for the community. In 2017, they performed three plays for a ticket-buying audience in Bengaluru. All the actors spoke to the audience about their stuttering before the show. "Being able to [act] publicly made me more comfortable with myself," says Saxena.

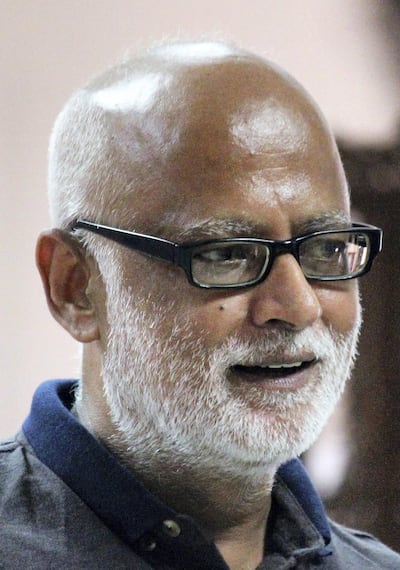

Acceptance is the most important thing that Tisa propagates. “We tell members that they are not alone and that stammering is not their fault,” says Dr Satyendra Srivastava, a physician and social worker from Dehradun, who founded Tisa in 2008.

Communication, he says, is a two-way street, and the responsibility of both the speaker and listener, in that the latter should have the patience to listen attentively to what is being said.

Founding Tisa

Srivastava started Tisa as a blog to pour out his feelings about his experiences with stammering. "There was a time when I let my happiness depend on the number of words I stammered in a day or not," he says. His outlook towards life changed with a chance meeting with a spiritual leader, who told him he was much more than his speech.

Tisa emerged as a multidimensional voluntary group because Srivastava wanted to provide a sense of community to people who stammer, so they don’t feel isolated. Twelve members volunteer their time regularly to support the group’s various activities. “We follow an old Indian belief, that serving others should be driven by empathy and care, not money,” Srivastava says.

Tisa is, however, limited in its reach to tech-savvy internet users. "We'd like to create self-help groups, and conduct workshops for teachers and parents in rural areas, but we don't have local partners," he says. "Thousands of kids who hide their stammer to escape ridicule could be supported."

Heart-warming success stories

As arduous as the condition is for many, the success stories are as heart-warming. Saxena says he looked upon his stammering as a penalty for crimes committed in his past life. Being a Tisa member has given him something he sorely lacked growing up, as he strove to keep his condition a secret: friends.

Stress and nervousness trigger a speech block for people who stammer. Dr Humayun Khan, 27, went through this when interacting with supervisors during his postgraduate entrance exam, thus ruining his performance. A single tip from Tisa – "keep smiling and maintain eye contact with the person you talk to" – has helped him stay calm in stressful engagements, he says.

Ashish Agarwal, 36, was so invested in attaining speech fluency during college that he ended up falling into a depression that lasted a year and led to a compromised lifestyle and psoriasis, an autoimmune skin disease. Once he became a Tisa member, he shifted his focus from fluency to effective communication. "The sense of belonging members find trickles down to other spheres of their life, too," says Srivastava.

Tisa provides a manual for parents, teachers and employers, which comes in handy when volunteers conduct free communication workshops in cities and participate in corporate diversity conferences.

Sensitisation has helped teachers understand that some children may not speak up at all because of their shame of stammering. Employers learn that it is a good idea to be patient and give a few extra minutes during interviews. Even a single convert goes a long way in influencing the life of a person who stammers.