Like a well-tuned chorus, the railways band, resplendent in its crisp, military-styled uniform, strikes up as the towering red locomotive of the Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express wheezes its way into Moscow’s Kazansky Railway Station. It’s nothing if not impressive, nine gleaming passenger carriages in azure blue, touched with gold lettering, and pulled by both an electric locomotive and, if only for the first hundred miles, a historic steam engine, complete with red Soviet star on its boiler plate.

Kazansky, one of nine railway terminals in the Russian capital, is a fitting departure point for the Trans-Siberian. Dedicated to the rail lines that radiate east to Kazan, Yekaterinburg and Vladivostok, the station’s soaring curved roof, bustling concourses, and steaming, chuffing trains offer the perfect send-off on the world’s longest railway journey.

No rail route has captured imaginations like the Trans-Siberian. Opened in stages between 1891 and 1916, this steel ribbon runs the length of the world’s largest country, offering a 10,000km lifeline that passes through eight time zones and across rivers, lakes and mountain ranges as it connects the west with the vast expanses of Siberia, the “Sleeping Land”, which sprawls from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific. The most expensive rail line ever constructed, it’s also a time machine of sorts, and travelling east across the permafrost of Siberia, the Trans-Siberian offers travellers a chance to step back through Russia’s rich and often tumultuous history.

With the band’s serenade comes the arrival of the guests, 69 on this run, who are guided by young stewards in freshly pressed blue uniforms. The traditional Trans-Siberian train journey may be iconic, but it also comes with challenges and discomforts, from language barriers and gruelling scheduling to the chance of an MSG overdose from railway catering. However, the Golden Eagle, a luxurious rendition operated by the United Kingdom’s Golden Eagle Luxury Trains, offers fine-dining, daily excursions, insightful lectures and plenty of privacy for guests across all classes.

My Silver Class compartment has a small table, a bench seat in blue velvet that my carriage’s shy, ever-smiling stewards Angeleka and Denis convert into a bed each night, an LCD screen that offers access to an extensive collection of documentaries, and a combination toilet and shower. There are little compartments for all my belongings and as I unpack we depart with a lurch and a bump, the locomotive chuffing and roaring up to speed, ranks of grim Moscow suburbs and factories topped with towering red and white smoke stacks quickly giving way to verdant countryside.

There has never been more interest in luxury rail travel and on this 12-day journey across Russia I’m joined by passengers from Australia, Holland, India, Singapore, Taiwan, Spain, the United States and Brazil. There’s even a jovial Dutch television crew filming the journey for a new series on Netflix called Cruise on Rail. We size each other up on the first night in the train’s two sumptuous dining cars, where we enjoy the first of many elegant meals, complete with cut crystal, gleaming silver, and ever-smiling young wait staff hailing from across Russia.

Nothing short of a tractor pull prepares you for sleeping on the Golden Eagle; while the bed is very comfortable, and the cabin cool and cosy, the train never stops its shuddering, samba-like sway as it races east, and at times I find myself gripping the bed’s wooden sides through the turbulence. Seemingly endless cargo and passenger trains race past, each a blur of colour and a roar of squealing wheels and howling horns. It’s both exhausting and exhilarating. However, the next morning we’re greeted by blue skies that reach towards the horizons, and the soft, motherly voice of our train manager, Tatiana, an Irkutsk-native, who briefs us on our first destination, Kazan.

Unlike the regular Trans-Siberian trains, the Golden Eagle’s itinerary is packed with optional excursions. In Moscow, we visited Red Square and the Kremlin before feasting on borsch and dumplings at the iconic Café Pushkin, while in Kazan, an ancient city at the confluence of the Volga and Kazanka Rivers that remains an economic and political powerhouse, we delve into the Unesco-listed Kazan Kremlin (the word simply means fortress in English and many cities have their own “Kremlin”), climb to a viewing platform within the spectacular Qolsharif Mosque, and listen to traditional Tartar opera over a gourmet lunch.

In Yekaterinburg, a city founded by Peter the Great in 1723 that was until the 1990s completely closed to foreigners due to its many armament factories, we step back in time again. Under a blazing mid-morning sky our guide Natalia whisks us to the spectacular Church of the Blood, built on the site of the execution of Tsar Nicholas II by the Bolsheviks. Russia is having a Romanov renaissance and the church was built in 2003 in place of the original structure, which was destroyed in the 1970s by then local party boss Boris Yeltsin (which he would later express regret for the act his memoirs), to tap into a growing reverence for Russia’s royal leaders past. From there I head for the Yekaterinburg Military Museum, an expansive collection of military hardware produced in the city, ranging from Hind attack helicopters and armored trains from Stalin’s era, to MiG fighter bombers and fragments of Gary Power’s US spy plane.

In Novosibirsk, or “New Siberia”, our first true Siberian city, we take a peek behind the scenes at the city’s breathtaking Opera House, one of the largest in the world, and trace the history of the Trans-Siberian Railway among the century-old locomotives of the Museum of Railway Technology. Further east, in Irkutsk, for centuries an important trading post between Russia and China, I learn to prepare classic Russian dishes like Schi soup, blinis and Siberian dumplings, before visiting a weathered mansion-turned-museum dedicated to the aristocrats that failed in their Decemberist uprising against the Tsar in 1825 and who were exiled to remote Siberia for their crimes. We spend the warmth of late afternoon dining on brilliant home cooking and testing our metal in a Russian banya sauna with the Shugantsev family at their countryside dacha, a collective of beautiful cottages wreathed by summer gardens. Outside Ulan Ude, on the cusp of Mongolia, we meet the Old Believers, a community of orthodox Christians whose ancestors fled the persecution of Russia’s 17th century Tsars, only to find a home in the often-harsh heart of Siberia, where temperatures can drop to below -40°C. Over a lunch of hand-rolled meatballs and cured fish, village elder Galina sings love songs and haunting dirges in her native tongue and tells of the year it took her family to walk to the valley she now calls home.

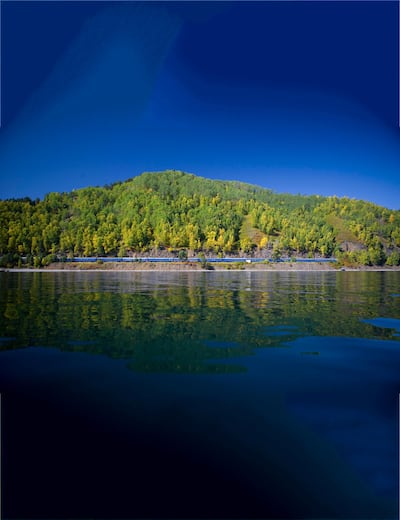

A highlight of the journey east is Lake Baikal, the deepest on the planet, and home to 20 per cent of the world’s fresh water. In a deserted cove where the train links up with another vintage Soviet-era steam locomotive that will pulls us around the sea-like lake’s edge, I join a few brave souls in taking an early morning dip, the freezing waters sending us howling and laughing for shore, truly invigorated. By dusk we’re enjoying a lakeside barbeque prepared by the train’s culinary team and capture the sunset over the lake’s dramatic setting.

A few days later our journey on the Golden Eagle is nearing its end. After a day spent across the border, in Mongolia’s manic capital city, where 15 guests friends depart the train, we set off three non-stop days of riding the rails to Vladivostok, during which there are chances to polish your Russian, attend guest lectures and piano recitals, or join Tatiana to discuss modern day Russia and life as a local. During this downtime, the train’s chefs also prepare spectacular Russian feasts laced with traditional fare, from sturgeon caviar and golubtsi cabbage rolls to zakuska, pickled vegetables. However, I spend most of the sprint across Siberia soaking up the wild landscape, with its birch and spruce forests, and riots of wildflowers, from my cabin.

Here in the far east, the sky turns heavy and silver, and pine forests arrive like the first dustings of snow; before long they dominate the horizon. Each passing village, with its timber houses the colour of molasses and beehives and flowering potatoes in the yards, is a legacy described in broken concrete and abandoned factories with darkened windows. In places it’s hard to tell where the wooden cottages end and the piles of winter firewood begin. Each settlement is seemingly under siege from the vastness of the landscape, each a swimmer clinging to the lifeline that is the Trans-Siberian. The signal fades from my phone as the light fades from the sky, and the air fills with pine and wood smoke as one cargo train after another passes, headed west from the Pacific into the interior.

We arrive in the port city of Vladivostok, our appetite for Russia’s vast wilderness sated, our understanding of this diverse and awe-inspiring landscape deepened. Will I miss the challenge of walking the train’s length while it shudders and jerks; the chance of being thrown from bed; the utter isolation from the world beyond? Perhaps not.

But I know I’ll miss the Golden Eagle, with its smiling crew who have all become friends, and I already miss Siberia, seeing Russia old and young, and the sense of discovery that await Trans-Siberian travellers around every bend.

___________

Read more:

South America's first luxury overnight train: on board the Andean Explorer

Driving through Siberia: on the road to Russia's spectacular north

Top 10 wilderness destinations

___________