I was back home in Christchurch recently, having lunch with a friend, when he made a startling revelation. "I bumped into some backpackers the other day," he said, nonchalantly, between mouthfuls of mince and cheese pie. "I got talking to them and they said: 'Obviously we're in town to see the mosque'."

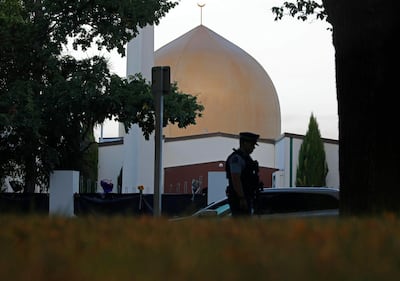

They were referring to Al Noor Mosque, where a terrorist killed 43 people and injured many more barely two months earlier. Suddenly, my pizza didn’t seem that appealing.

I suppose, in some respects, we should be thankful that tourists are returning at all. In the wake of the city's deadly earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, Christchurch was basically an airport and a highway to other South Island towns that weren't half destroyed. Tourist numbers plummeted. But I felt a strange sense of unease knowing that people were now seemingly only coming here to visit the site of such tragedy – perhaps because they had seen it on the news. Didn't they know about Sumner Beach, or the Port Hills or the Christchurch Tram? Couldn't they go there instead?

Perhaps it's unsurprising that this should also happen in New Zealand, given that the caves in Thailand where the Wild Boar soccer team were trapped have become a tourist attraction; local authorities in Colorado are considering destroying Columbine High School in Colorado, the site of a deadly mass shooting 20 years ago, due to people's "morbid fascination" with it; and there has been an exponential rise in visitors to Chernobyl, coinciding with the HBO TV series of the same name. Only one of these examples had a happy ending.

Dark tourism is certainly not a new phenomenon, but is our macabre obsession ramping up? And is social media to be the scapegoat, once again? “I call it an old concept in a new world,” says Dr Philip Stone. And he should know. Stone is possibly the world’s foremost expert on the matter – his fascination with the subject of dark tourism led to a PhD in the study of death, with a focus on tourism, and to him now sitting at the helm of the Institute for Dark Tourism Research at the University of Central Lancashire.

“It was big in the 1980s and 1990s, but it’s been around much longer than that without a label. People are visiting these sites and that’s always been the case … what’s happening now is there’s more media and more social media spotlight on it.”

How, then, do we differentiate between those paying respects to the scene of a tragedy and those visiting purely so they can pop it up on their Instagram feed, so everyone can marvel at their cultural awareness and empathy? Is there a difference between visiting Al Noor Mosque and taking a trip to Auschwitz in Poland, where more than one million people were killed and where a record-breaking 2.15 million people visited last year?

Auschwitz’s success as a tourist destination ultimately rests on the fact that it has been set up as a harrowing testament to an unthinkable tragedy; a lasting memorial to ensure nothing similar ever happens again. Stone reasons that it is all in the “authenticity of the message”, and how we consume that experience. “There’s a drive to bring people in ... you can fly directly into Krakow now. And that’s the same with commercial tourism.

“It’s also about the portrayal of death and how we showcase it; people can be normal in life and become significant in death. The second thing is the chronological distance, where it passes from heritage into history.” The problem, Stone adds, is that passage of time is becoming shorter and shorter.

Perhaps that’s why the idea of people visiting Al Noor Mosque so soon after a tragedy has occurred elicits feelings of unease or even outright disgust. Almost eight decades have passed since Auschwitz was in operation, so perhaps it has officially transitioned from a voyeuristic experience to an educational one?

It was within days of 71 people dying in the Grenfell Tower fire that nearby residents began erecting hastily scrawled posters urging people not to treat the building as a tourist attraction. Too many tourists had come in to take photos of the still-smoking husk. People were still missing at that stage.

“Rescue operations were still going on and people were taking selfies,” Stone says. “It happened with Hurricane Katrina; bodies were still floating in water and people were coming down to take a look.”

Surely then, it’s about being respectful, and visiting these places with the intention of paying tribute, rather than simply hoping to bag a social media post and move on. This is an issue that Israeli artist Shahak Shapira highlighted with her Yolocaust project, where she juxtaposed snaps of irreverent tourists at Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe with historic photos of the people suffering through the horrors of the Holocaust. The result sees posing tourists atop mass graves of the emaciated dead or dying – in some instances doing yoga poses, juggling or jumping up gleefully.

The series quickly went viral, and for a fleeting moment it seemed to shame the mass tourism market into uneasy silence. And then Chernobyl, the TV series, came along.

Tourists have flocked to the Ukrainian site in the wake of the HBO drama (in many cases, it appears, without having any prior knowledge of the disaster). Selfies besides deserted buildings in the abandoned town of Pripyat, untouched since the 1986 power plant disaster, have riled the internet. One woman even felt it necessary to pose at the site half-naked. This has caused the show's writer, Craig Mazin, to publicly urge travellers to show respect. "If you visit, please remember that a terrible tragedy occurred there. Comfort yourselves with respect for all who suffered and sacrificed," he wrote on Twitter.

“There is a sense of media validation,” Stone says. “But over-tourism and dark tourism have almost created this perfect storm. People have been learning about it at school and then going to a particular site because they can.”

So how do we visit these places respectfully? I’ve been to Chernobyl, Auschwitz and Fukushima … and I’ve taken photos. Am I any different?

I hope so. I was living in Japan when the tsunami hit, and I was volunteering up north in the wake of the nuclear fallout. Did I take photos? Yes. Were most of the photos taken courtesy of the Japanese women collaring the two western males I was travelling with? Absolutely.

My visits to Chernobyl and Auschwitz, however, were purely tourist ventures, which admittedly felt slightly strange to organise. That feeling intensified while watching groups taking selfies outside gas chambers, or outside the dome of a nuclear power plant. My only regret is partaking in the latter; my awkwardly half-smiling face directly contradicting the snow-laden wasteland I was framed by.

The lessons I learnt on these trips? Be respectful. Silently take in the history. Listen to your guide. Don't take photos in front of large "no photo" signs. Remember where you are.

Stone is currently working on a book on this very subject – an etiquette guide for the commercial market. He isn’t sure that there’s a clear-cut distinction between types of tourists, though. He points to the “dichotomy” of travel (“the argument that a tourist is a passive observer, whereas a traveller is more seriously engaged”), but says he doesn’t necessarily buy into that.

“It’s not about telling people how to behave if something’s happened tragically there, it’s about understanding the context,” he says. “What we’ve got to do is look at these sites and how they are packaged up and exploited by tourism.”

Meaning, perhaps don't take that selfie, or buy one of those souvenirs at the roadside stall beside the exclusion zone near Pripyat. You know, those ones branded with bright yellow nuclear symbols on everything from pens to T-shirts.

After all, a few days after that lunch conversation, I went to Al Noor Mosque, too. I stood as Muslims arriving for prayer greeted me warmly. It felt right for me to be there to pay my respects. It’s a fine line to tread – but if in doubt, just don’t take the selfie.