We’re told that the acceptance of electric vehicles is good for the environment and great for the wallet because you’ll never have to visit another petrol station. Simply plug it in at home and count the savings. Right?

Unsurprisingly, it’s not that simple. In time, EVs may tick those boxes, but for now, the car industry and global governments are sweet-talking early adopters who are prepared to take the financial hit to fund the industry’s way through the costly development process.

Diesel fuel in an EV era

Elmar Degenhart, chairman of the executive board for Continental, which develops electronics for the world’s biggest car makers, said that if everything is taken into consideration – including the manufacture and operation of EVs, the diesel fuel needed to mine the rare minerals used in batteries and the production of the energy itself – emissions can be reduced.

“You can reduce CO2 emissions to about 25 per cent of a reference range to the gasoline vehicle if you’re using renewable energy with a battery electric vehicle, while a fuel cell vehicle can be slightly below that,” Degenhart says.

However, that will cost an average of Dh45,000 per car, which is passed directly on to the consumer.

Purchase prices change the game

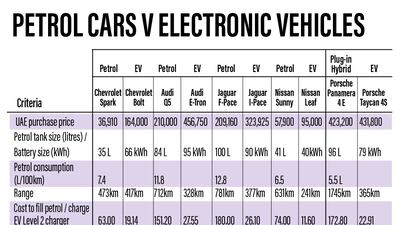

A snapshot of EVs in the UAE shows that running costs compared with their ICE equivalent is comfortably in favour of EVs by an average of 64.4 per cent. But when you add in the purchase price of the cars, the scales tip back in favour of petrol vehicles over five years, to the tune of 42.6 per cent.

Take the Jaguar F-Pace 2.0 turbocharged, four-cylinder SUV and the similar Jag I-Pace electric SUV as examples. Including the purchase price, the buyer of the F-Pace will spend an average of Dh48,747 per year over five years compared with Dh66,861 for the I-Pace.

When comparing other like-for-like models, such as the Chevrolet Bolt vs the Chevy Spark, the Nissan Leaf vs the Nissan Sunny and the Audi Q5 vs Audi e-tron, the story is similar (see table).

As an alternative, to show the difference a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle would make, we included a Porsche Panamera 4 E against the new Porsche Taycan EV, which shows a 36.6 per cent benefit in running costs for the Taycan over five years, but a near line-ball 0.72 per cent swing to the Panamera after the purchase price is included.

The UAE is the most developed EV market in the region, registering just over 2,000 units since 2012 with a 250-strong charging infrastructure in Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

EV incentives in the UAE

In 2017, the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority, together with the Roads and Transport Authority, announced an incentive offering free parking and free charging at public stations, Salik exemptions and discounts on registrations.

“Since Dewa launched the EV Green Charger initiative in 2015 and its free charging incentive, there has been a significant increase in the number of electric and hybrid vehicles in Dubai,” says Saeed Mohammed Al Tayer, managing director and chief executive of Dewa. “Due to the positive response, we have extended the free charging incentive for non-commercial EVs to December 31, 2021.”

The extension to cover the 0.29 fils per kilowatt hour charge applies to private users only upon registration for the EV Green Charger initiative, but doesn't include home charging.

Fast charging is gaining popularity in Europe and the US for an added cost, and is the figure quoted by manufacturers when estimating rapid charge times, but it has yet to be installed in the Middle East.

Instead, the commercially available, public charging points at malls, business towers and at home are the global standard “Level Two” units and installing one of these ranges from Dh1,000 to Dh5,000, depending on the supplier.

Sluggish sales for now

The global market for PHEVs and EVs in 2019 closed at only 2.5 per cent, representing two million sales despite heavy government incentives such as free parking, toll exclusions, free charging, discount financing and reduced or zero road taxes.

Ford’s big F-Series pick-up truck was again the top seller in the US with 897,000 units sold in 2019, while one in three new cars sold in the UK was still a diesel. EVs account for 1.6 per cent of the UK market with 37,850 units, but for pure EVs (not including PHEVs) to make up 10 per cent of the global market, there needs to be annual sales of 1.7 million units as opposed to the 400,000 registered last year.

Synthetic fuels and new tech

Despite this, zero pollution remains every manufacturer’s goal and long-term it will happen, but probably not with EVs. New technology that’s cheaper, more practical, environmentally kinder and even greener than electricity is constantly being developed, and the Middle East is a leading player.

Renewable synthetic fuels, such as the type Saudi's Aramco is developing through its technical partnership with Formula One, allows regular combustion engines to run without emitting any CO2, which makes them as clean as EVs. Plus, given that there is no mining for rare metals such as lithium and cobalt used in the manufacturing of batteries, it's also less harmful to the environment than EVs.

Zero-emission liquid fuels that use existing combustion engines and take minutes to fill is a real possibility further down the track but, for now, buying an EV will feed the soul before it feeds the planet.