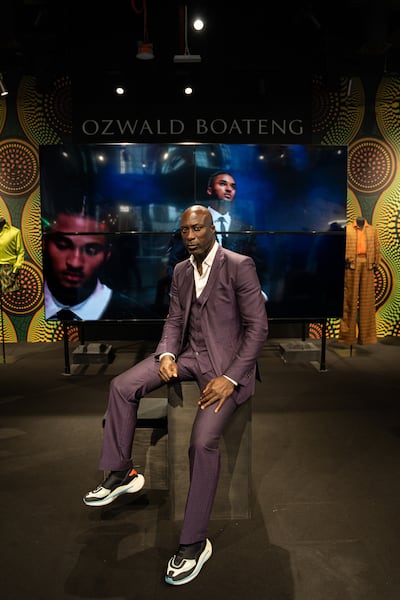

“This is the thing about life. No matter how many successes you have — and I have had many — it’s the gratitude. You have to be grateful,” says British-Ghanaian fashion designer Ozwald Boateng.

In Dubai to launch his latest ready-to-wear capsule collection, called Black AI, with the initials standing for authentic identity, at That Concept Store in the Mall of the Emirates, Boateng could be forgiven for feeling self-satisfied. He was the first black man on Savile Row and the first tailor to show at Paris Fashion Week. He also served as the creative director for menswear at Givenchy and has been awarded an OBE.

But, now in his mid-fifties, Boateng is more philosophical about the path his life has taken.

“Success and failure live in the same chair with you, because the failure is the learning. It’s always about the experiences, I have learnt. They are key," he tells The National.

While that journey has brought him fame and success, it has not always been a smooth ride.

“I went to school in the 1970s and culturally I grew up in a time when racism was real. So being chased down the street was a daily exercise,” he says.

“I had a very strong belief in myself because of my father — he gave me a lot of confidence — and he brought me up with a certain sense of self. I was never unsure about me, but put that in the landscape of racism and it was tough. I had a lot of fun as a kid, but I used to get chased because I was black.”

Born to Ghanian parents and immensely proud of his heritage, Boateng realised that he wanted to be able to change how people of colour were perceived.

“At the time, there were two routes,” he says. “People could get very angry about racism, or they could work through it, and I choose to work through it.”

Boateng’s chosen route was via fashion, after it became apparent that he had an unwavering instinct for tailoring and an almost poetic command of colour. By the time he was 17, he was being urged to take his talents to Savile Row, the bastion of British bespoke suit-making.

“A friend of mine, the artist Duggie Fields, said to me: ‘You need to go to Savile Row’. My response was: ‘What, those dusty old men? Why am I going to go down there?’”

What Fields seemingly understood, before Boateng, was that if this cocksure, talented young black man could win over the “dusty old” sphere of white male privilege that Savile Row represented, he would have the world at his feet.

At that point in the 1980s, tailoring as an art form was dying, as designers cut their suits loose and boxy. Despite being the heart of bespoke tailoring since the 1790s, Savile Row was losing its relevance, the relic of an outdated era.

By contrast, Boateng’s suits were beautifully cut, tailored for a slim, elegant fit, and came lined in jewel-toned silks in purple, orange or fuchsia. Although only in his twenties and almost entirely self taught, in 1994 he took his collection to Paris Fashion Week — the first tailor to do so. As the press waxed lyrical about this vibrant new talent and customers lined up outside his door, he opened his first shop on Vigo Street, just off Savile Row, in 1995, becoming, at the age of 28, the first black man to ever do so.

His dazzling cuts drew in a new generation of customers, and with clients such as Forest Whitaker, Russell Crowe, Daniel Day Lewis and Spike Lee, Boateng is credited with reviving suit-making, saving Savile Row from extinction in the process.

In 2003, he was appointed creative director of menswear at Givenchy, a position he held until 2007. In 2005, he was invited to be part of the Fashion in Motion series at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, delivering a collection that mixed burnt orange with lavender, royal blue with periwinkle, and caramel with mustard.

His dapper tailoring appeared in the films such as Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Tomorrow Never Dies and The Matrix, and in 2000, he won Best Menswear Designer at the British Fashion Awards. Away from fashion, in 2008, Boateng was appointed to the Reach committee, to help inspire and motivate young black boys, and he co-founded the Made In Africa Foundation, a non-profit aiding development across the continent. In 2006, he received an OBE from Queen Elizabeth II for services to British fashion.

“I put in the work,” he says. Yet, while achieving all these personal career highs, he maintains he always had a greater purpose in mind, but had to keep it hidden. “I have only been able to have this conversation recently,” he explains.

“When I get asked about where my design ethos comes from, it’s so beyond fashion and so rooted in culture. I couldn’t talk about racism when I started, because I would have been seen as the angry young man, and I didn’t want what I created to be confused.”

As a man of colour, Boateng has always seen it as his responsibility to excel in his field and open doors for others. “I knew that my being on Savile Row and having shows in Paris had cultural implications. And to have the right impact, you can’t shout, you have to just do it by being present.”

While successful, the ploy has at times backfired, as evidenced during the rise of Virgil Abloh.

“I knew what I was doing, but it’s funny, people forget that I was at Givenchy. When Virgil Abloh became creative director for menswear at Louis Vuitton, they talked about him being the first black designer.”

In reality, Boateng preceded Abloh as the head of a major fashion house by 15 years, something all but forgotten today. But while that smarts, he understands why his achievement is often overlooked.

“I didn’t position myself like that. Instead, I positioned myself just as a creative who happened to be black. I took that position to say, what’s the big deal? You are judging the creative, not what the person looks like.”

In 2018, Boateng shifted his cultural heritage front and centre, holding his first show in years at the Arise Fashion Week in Lagos, Nigeria. Unveiling his first ready-to-wear collection during a show called Africanism, it was something of a stylistic evolution — with his signature clean silhouettes and rich colours now decorated with patterning taken from traditional Ghanaian kente cloths, as well as the Adinkra phonetic alphabet.

In 2019, Boateng released its second iteration, called AI, at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York. The choice of location was important, he explains, because “in terms of African-American history, it is the church of churches. Everyone from Ray Charles to Gil Scott-Heron to James Brown has performed on that stage.”

Timed to coincide with the anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance, it was also his first foray into womenswear, a move inspired largely by his daughter. To accompany the show, Boateng had the all-female African-American Harlem Orchestra play live.

“The energy in that space is beyond imagination,” he recalls. “We were the first fashion show to be held there, and I got to sign my name on the wall among all those greats. So again, it’s back to gratitude. It was a real privilege.”

Deeply impacted by the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, for the third chapter, called Black AI, Boateng doubled down on the idea of blackness and black excellence.

To press this idea home, for the finale, Boateng appeared on stage with actor Idris Elba. The much-anticipated show was held in February as part of London Fashion Week, and marked the designer’s return to the British fashion calendar after an absence of 12 years. It is this collection that is now on sale in That Concept Store.

Comprising lightweight silk bomber jackets, woven tank tops, seersucker shirts and fluid, floor-length kimonos, the collection is decorated in the same vibrant Ghanaian patterns, some literal and others a little more discreet, including an intricate motif that turns out to be a letter from the Adinkra alphabet, repeated over and over. Colours are bold and invigorating, shifting from zesty lime to teal and from red to regal purple.

While it is being marketed as ready-to-wear, the collection has been conceived more along the lines of bespoke — with three patterns and 12 colours — and is available in limited editions, meaning once it’s gone, it’s gone. While Black AI represents the third chapter in the story, there are, he promises, two more to come.

Reminiscing on a career spanning 30-odd years, Boateng explains that while much has changed in terms of black acceptance, there is still a lot more to do.

“When I was growing up, in terms of black representation, the first British black face I saw on television was [the comedian] Lenny Henry. There were no other reference points," he says.

“So when I got my first bit of media in the 1980s, I knew what that would mean. I was more than just a designer, I was a Savile Row tailor, and the message was, if I can do that, so can others."

Now, he has people coming up to tell him he was their “first reference point”.