Sarah Burton, the creative director of Alexander McQueen, is a quiet sort of iconoclast. Where some shout their nonconformism, Burton prefers to whisper; case in point, Process, a new exhibition that has recently opened in London.

Held inside the vaulted space of the brand's flagship on Old Bond Street, Process is a visual discussion about the collaborative nature of creativity, how it stems from myriad viewpoints and how female artists are shaping a unique narrative. For this project, which will be on display until June 21, Burton invited 12 international female artists to reinterpret a look from her autumn/winter 2022 pre-collection. As well as presenting a final artwork, each artist was requested to document her creative journey, which in turn gave the project its title.

“I wanted to engage in a new creative dialogue with the collection this season and see how the artists interpreted the work we created in the studio,” explains Burton. “It’s been very interesting to see how creativity has sprung from so many different perspectives, and the outcomes have been varied and beautiful.”

Given a completely free hand, each artist was left to select the look or looks that spoke to them. Norwegian artist Ann Cathrin November Hoibo, for example, selected all the pink and red looks from the collection because, as she explains: “I wanted to make a warm and very feminine environment.”

With the looks hanging physically in her studio, Hoibo created a giant tapestry inspired by the folds and shadows of the clothes, and using the same materials — wool, cotton, poly faille and satin. The finished work hangs from a bar of hard Perspex, highlighting the softness of the weaving.

“With so much masculine pressure going on in the world, it’s important to keep the heart soft. The Alexander McQueen looks inspire me in that way, the gentle and feminine inside with a harder cover for protection.”

For Chilean sculptor Marcela Correa, meanwhile, inspiration came from a canary yellow off-the-shoulder, full-skirted corset-dress, with what Burton calls an “exploded neckline”. Correa created two amorphous figurines in the same bold colour, built from a papier mache of resin, paper, magazine cuttings and fibreglass, applied in slow and deliberate layers. To the strange curved forms, Correa has added faces, collaged from fragments, which speak of “absent faces and broken memories”.

Interestingly, American artist Beverly Semmes chose the same dress, yet her treatment could not be more different. In perhaps the most visually arresting piece in the exhibition, Semmes has created an oversized velvet robe that flows down on to the floor.

As with much of her work, this is about the representation of women in the media, and a marigold yellow dress spills from the velvet robe, which in turn becomes a pool of pink organza on the floor. On these waves of fabric sit a pair of shoes, a bag — both made from duct tape and paint — and even a dog.

As Semmes explains, the pup was not part of the original plan. “As I worked, my dog spent time most of the day napping in and around the artwork. This led me to unearth a life-size replica of a Labrador retriever purchased decades ago. With the gold chain from the clutch purse placed around his neck, he took to the pool like a natural.”

American photographer Jackie Nickerson, meanwhile, choose an off-the-shoulder pencil dress in deep orange poly faille, which she then documented herself wearing.

In the resulting images, she and the dress are almost completely obscured behind a shroud of seaweed and recycled material.

With her work focused around nature and its pollution, Nickerson explains her inspiration was twofold: Alexander McQueen's love of nature and Burton’s description of her designs being “soft armour for women”.

“The materials I used are a reference to the sea and the challenges we face with marine pollution.”

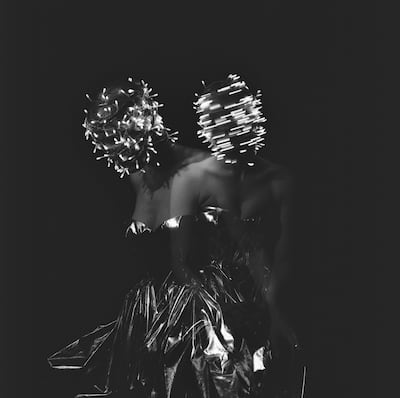

American artist and model Guinevere Van Seenus based her work on a strapless corset dress in crushed silver poly faille. With the gown made from metallic cloth, Van Seenus was keen to capture the play of light across its surface.

The result is a series of small Polaroid photographs of Van Seenus wearing the dress and a garland of fairy lights. “I love the play of how light opens up on film, dots of light, reflections, blasts of light that reveal everything. I work alone and try to make friends with the accidents that happen on film and Polaroid.” Manipulating the photographs as they developed, Van Seenus added marks and dashes, as well as beading, carefully hand-stitched through the image.

British artist Judas Companion, in contrast, based her several works on two oversized suits in electric blue. Realised as a series of wearable “masks”, each one is made using electric blue mohair knitted into a balaclava, on to which the artist has added facial elements, such as eyes and a mouth, using concrete, faux fur, plastic, ceramic and paint.

While the masks act to obscure the face beneath, the grotesque features instead create a new, twisted persona. Companion describes her work as “revolving around metamorphosis in the widest sense. I paint, I make masks, I photograph and film myself visualising processes of transformation. I turn my inner world outside and make emotional turmoil visible.”

Chinese painter and sculptor Bingyi, meanwhile, based her work on a corset dress with oversized silver metal hook-and-eye detailing.

From these she created two new outfits: a wedding dress and a groom's suit from ink drawings, linen, cotton and paper. Called The Wedding Dress that Takes Off Itself, the artwork is about duality and ritual — signified by the wedding gown —and how we travel though life.

The papery white gown has been created to resemble “a waterfall that flows off a woman’s body”, she explains, while the man’s suit is printed in Chinese messages of love.

“We wanted the artists to have total freedom to respond to the looks, creating bold and thought-provoking conversations with their works,” Burton says. “I hope viewers will be as inspired as we have all been by witnessing these creative processes.”