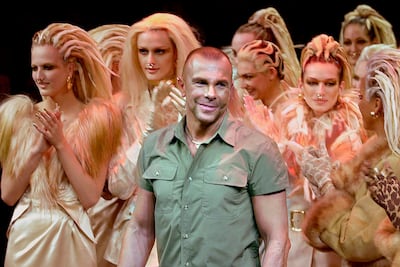

Perfume lovers who learnt about the death of the hyper-creative French fashion designer Thierry Mugler this week may well have memories of wearing not his clothes but his scent. Mugler’s Angel was something else. Unexpected and fun – like his clothes – the perfume was an olfactory shock when it was launched in 1992. And 30 years on, it is still a global best-seller.

While Mugler’s clothes were prohibitively expensive, pretty much everyone could afford to buy Angel, and there was a time in the mid-1990s when it was olfactorily clear that pretty much everyone did. But it was initially a slow-burner, introduced when the overpowering scents of 1980s perfumes had given way to clean, fresh, simple scents.

Angel’s creators, perfumers Olivier Cresp and Yves de Chiris, took inspiration from Mugler’s childhood memories of nights at the funfair. Notes of praline, bergamot and vanilla danced on a massive 30 per cent bed of woody patchouli. Those who lived in New York in the 1990s, as I did, may remember how one had to dodge the manically animated Angel spritzers in the perfume aisles at Bloomingdale’s. A lot of people recoiled at first inhalation.

But there was – is – something truly enchanting about that perfume. Angel was intriguing: complex, lively, sweet but somehow not cloying, girlie yet in due course a favourite with many boys, too. By about 1995, you could hardly visit a restaurant or cafe in New York and not notice someone trailing the bizarrely addictive Angel.

And the bottle, still one of the most distinctive on the market, must have helped sales: blue glass, shaped like a star. In his twenties, Mugler, then a ballet-dancer turned fledgling designer, was apparently told by a fortune-teller that the distinctive star on his palm not only signified success but was a shape he should incorporate into all his work to guarantee continued good luck.

Angel heralded a new era of creativity. Pandemic pauses notwithstanding, there are more independent perfumers and "noses" at work today than ever. When interviewed, many cite Angel as a key olfactory memory. For better or worse.

As a result, the future of perfumery looks bright. Paco Rabanne has just partnered with Maximum Games to produce “the world’s first connected fragrance” with an in-game character representing its new launch, Phantom. Japan and Korea are innovating with perfumes in the form of powders, gels and roll-ons. Millennials and Gen Zs are reportedly looking for ungendered fragrances, customisation, recyclable packaging, refillable bottles, removable pumps to make recycling easier, vegan ingredients, transparent sourcing and artisan makers.

Despite organic being such a magic buzzword, perfumes are one area where it’s generally accepted that it’s better that the synthetic versions of traditional natural ingredients are used, whether animal ingredients such as musk from deer, castoreum from beavers and ambergris from sperm whales, or of vulnerable plant species such as Indian sandalwood.

But as French perfumer Guy Delforge commented a few years ago: “Perfumes have existed for 5,000 years and the scents haven’t changed much.” Roses, jasmine and bergamot were used in Ancient Egypt and they’re still the most popular ingredients in use today.

So, in memory of Mugler, here are five other groundbreaking scents that have stood the test of time.

Jicky by Aime Guerlain, 1889

You can date the start of the modern perfume industry to the 1890s, when two chemists in France, Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Eugene-Melchior Peligot, isolated the main aroma compound in cinnamon oil, the molecule cinammaldehyde.

That momentous breakthrough heralded the arrival of synthetics, or chemical copies of natural ingredients, and was quickly followed by the isolation of the key molecules in hyacinth, vanilla, bergamot, lavender, mint, jasmine and rose, allowing chemists and perfumers to recreate their fragrances at will.

Up until then, throughout history, perfume had been derived from the real and often rare thing, whether flowers, leaves, barks or oils. Whether it was the oldest record we have of fragrant incense being burnt, in China in 4500BC, the Kyphi used for temple offerings in Ancient Egypt in 3000BC (the recipe for which you can still see today, in hieroglyphics on the wall of the temple of Edfu) or the delicate rose perfume, created in the 10th century by the Arab physician Avicenna, who invented steam distillation, perfumes had been rare, precious, expensive and only for the wealthy.

The most talented of the chemist-perfumers to use synthetics was Aime Guerlain, who employed vanilla, lemon, bergamot, lavender, mint, verbena and sweet marjoram, with civet oil as a fixative, to conjure up the "sublime, sensual" Jicky. He followed that in due course with the smouldering, still-adored Shalimar.

Parfums de Rosine by Paul Poiret, 1911

This was the first designer perfume, produced by the flamboyant Parisian couturier Paul Poiret, whose love of opulence and Arabian legends such as One Thousand and One Nights had him known as "Le Magnifique" after Suleiman the Magnificent.

Nuits de Chine and L’Etrange Fleur became hugely popular during his lifetime, their rich complexity complementing his sensual, fluid clothes – light, delicate, chiffon and silk kimonos, harem pants and turbans that were light-years from the stiff corseting women had been obliged to dress in for the previous 50 years. The elegant little parfumerie still exists, close to the Louvre on Palais Royal.

Chanel No 5, Gabrielle Chanel, 1921

While holidaying in the South of France, near Grasse, where rose, lavender and jasmine were grown for the fledgling perfume industry, Gabrielle Chanel met Ernest Beaux, once perfumer to the Russian tsar, and realised that here was the man to create her a perfume “for the modern woman” who wore her striking, casually elegant clothes.

Of the 10 samples he produced, Chanel’s favourite was number 5. Jasmine, rose, vanilla and sandalwood were the main ingredients, along with aldehydes – 10 times what Beaux had intended, apparently, thanks to a mistake in the mixing by an assistant. As the online site The Perfume Society says, it’s the aldehydes that “almost propel the fragrance out of the bottle”.

Opium, YSL, 1977

First and most famous of the big, flamboyant scents that had wearers in big shoulder-pads power their way through the 1980s. Sultry, sensual, spicy and long-lasting, Opium bloomed with notes of mandarin, plum, clove, jasmine, rose, lily of the valley, cedar, musk and patchouli. In New York, the perfume’s launch party took place on a tall ship, The Peking, rented from the South Street Seaport museum and decorated with white orchids and banners of red and gold to echo the perfume’s packaging, with writer Truman Capote holding court in the prow. Chinese-Americans demanded that Yves Saint Laurent apologise for the name and for his “insensitivity to Chinese history” and the subsequent controversy helped publicise the scent and speed it to star status.

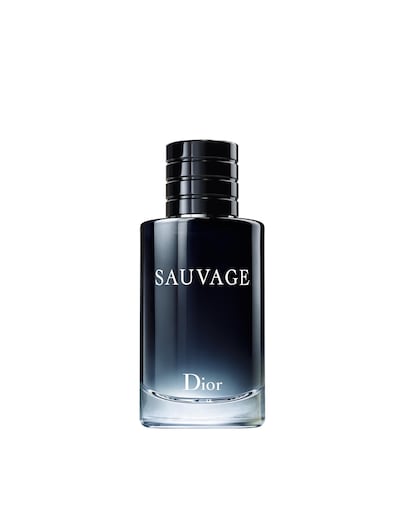

Sauvage, Dior, 2015

Created by Dior perfumer Francois Demachy, who took his inspiration from the desert at twilight, the men’s fragrance is a woody, smoky, subtle creation that has managed to survive the publicity around the court case involving its “face”, Johnny Depp.

This week, Dior announced Sauvage was not just a best-seller but the single best-selling fragrance in the world. One might have guessed that accolade would have been accorded to Chanel No 5 – and it is an intriguing demonstration of the male adoption of the fragrance habit. With sustainability becoming a driving force in fragrance, Dior is keeping abreast of current trends by having its distinctive bottles now 100 per cent refillable.