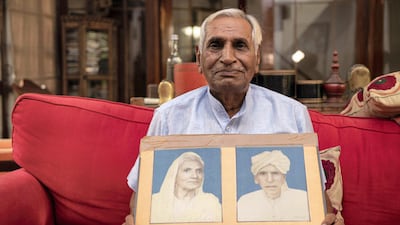

Ishar Das Arora, was born in Bela, a small village in West Punjab in 1940. Ishar was 7 at the time of the India-Pakistan partition, when his family – alongside millions of others – fled their homes and crossed the border into what had overnight become a different country. He eventually moved to Delhi after living in many refugee camps.

Kamala Devi, a Sindhi Hindu migrated from Pakistan to Barmer in Rajasthan at the age of 13. She remembers the temple in her village where the elders would sing folk songs. Her family members still remain in Pakistan, but Devi has never been back.

The divisive India-Pakistan partition

When Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a colonial-era British lawyer, was assigned to draw a demarcation line between British India's Hindu and Muslim territories in a span of five weeks in 1947 – one of the most controversial borders drawn – it displaced millions of residents as the soon-to-be-independent country was divided into India and Pakistan, with the eastern territories later becoming Bangladesh.

More than 12 million people were uprooted and, amid communal violence, hundreds of thousands killed as Hindus fled to independent India and many Muslims fled to Pakistan.

Life comes full circle

Ishar's grandson, Sparsh Ahuja, went on to co-found Project Dastaan, an Oxford University-backed initiative, which reconnects displaced survivors of the 1947 partition with their former homes. "Dastaan" means story in Urdu, and stories are what this project is all about.

The initiative aims to give emotional closure to the survivors of the partition and promote peace between the two countries, by connecting refugees from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to their ancestral homes and communities through VR technology and digital experiences.

The project also wants to showcase the experiences that people of various ethnicities and religions underwent on both sides of the border. Most people’s knowledge of the partition comes from oral accounts by family members, which may be lost forever if not recorded.

“Project Dastaan came into being through a casual conversation between a group of Indian and Pakistani friends at Oxford, when we discussed how difficult it was to help our grandparents travel across the border and return to see their ancestral villages in India or Pakistan, because of the constant uncertainty and hostilities in the relationship between the two countries, the difficulty in getting visas and the wired borders,” says Saadia Gardezi, another co-founder of Project Dastaan.

Gardezi, a Pakistani, grew up listening to tales of partition and refugees from her mother and her grandmother who had volunteered at refugee camps in Lahore. The third member of the team – Sam Dalrymple’s grandfather was a British officer stationed in India during the last stages of colonial rule, and who was terribly scarred by the partition.

Emotional reunion

“It’s a passion project between friends with historical family links to the partition; none of us are [history] experts, but we realised that with just a GoPro and VR technology, we could connect some of the former refugees with their ancestral environments. The project is funded by grant bodies, private donations and cultural organisations such as the British Council,” explains Gardezi.

“Working on this, you get a very close and eye-opening view into history and life in undivided India. Interviewing partition witnesses, seeing the other side, the life they had to flee from, and then giving them a view back into it, is very special.

“Also the reactions of children and grandchildren to a place they have never seen before in their lives, but have heard of, is very exciting. It often initiates a conversation with their grandparents about their past lives,” says Dalrymple.

“One of the partition witnesses whom we worked with was Dr Saida Siddiqui, who had migrated from Lucknow to Karachi,” he continues. “Saida has never been able to go back to Lucknow, but still considers it as her home.

“We located the old mandir [temple] opposite her home in Lucknow and the pandit [priest] whom she had played with as a child and shared mithai [sweets] with. The priest and her neighbours had a telephone call with her, and it was such an emotional moment that we were glad we could facilitate,” says Dalrymple.

Tech talk

Project Dastaan also has a team of young volunteers interested in history and the partition, and they connect with survivors through social media as well as submitting stories through its website. Many tech-savvy young people help the older generation come forward and share their traumatic experiences; many grandchildren connect on behalf of their grandparents.

Besides the social-impact VR project, Project Dastaan is also making The Child of Empire, an animated VR documentary film that puts its viewer in the shoes of a migrant in 1947; and Lost Migrations, a three-part animated series that tells less-known tales of the partition.

I ask Gardezi how the team manage to track down a place just from the memories of the survivors after more than 70 years. “When we interview the refugees, many have very specific memories of their village and their homes – from what trees grew there to the mosque or the house itself, and its structure. We ask them where they played as children and who their neighbours were. Of course, Google maps makes it easier to plot the probable location.”

The team then uses volunteers in both countries to track down specific places, sometimes making phone calls to witnesses after reaching the spot to confirm details before filming. Places of worship – both temples and mosques – they say, have been great pointers. The places are then shot and edited to six-minute films, and finally shown to the survivors and their families.

The Project Dastaan team had a goal to connect 75 partition witnesses with their ancestral homes by the 75th anniversary of the partition in 2022, but the pandemic has stalled those plans. The team do hope to finish 25 to 35 interviews by next year.

“The project has been a great catalyst for young and old to have conversations about a difficult time in history. It also aims to give the world outside this region a glimpse of an event with far-reaching consequences, which few outside these countries know in detail. It also facilitates a peace-building conversation between the two countries, especially between young people with a shared heritage,” says Gardezi.

“Many times, when the interviewees put on the VR glasses, they become so emotional at being able to revisit the place they were forced to leave as children, they just stand up. Even tough and strong men have had tears in their eyes as they walked down memory lane.”