The shell of a former nightclub in Beirut is now a makeshift kitchen that prepares more than 1,000 meals a day from a giant community oven.

The Great Oven project was started by James Gomez Thompson a few years ago in Tripoli, Lebanon, after he visited from London, where he worked as chef and creative partner to food writer and BBC broadcaster Nigel Slater.

Thompson and American street artist Shrine decided to see if they could get people on the front lines of the city's Sunni and Alawite conflict interested in painting street murals or cooking for, as Thompson puts it, "a sort of rehabilitation through food and the arts".

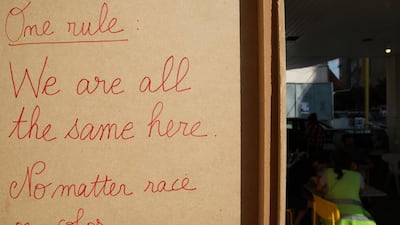

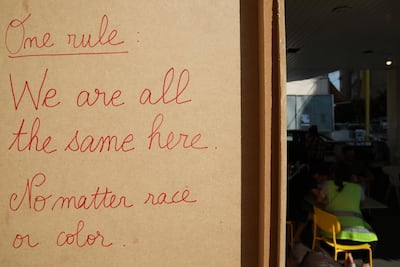

A safe space

They worked with members of the community to build an oven and decorate it, then made its location a safe space for people to visit. Often, DJs spin tunes while people gather to cook, collect food or simply hang out.

“These were people who had literally been killing each other,” Thompson says. “A lot of these guys were radicalised at age 12 or 13, and a lot of them were very scared. But they had a safe space with us.”

Ex-fighters, Iraqi refugees, women who were part of the kafala system, under which migrant workers in Lebanon are employed, and more gathered around the oven.

“We welcomed the most marginalised people in the country, and there was always a bit of art, food and security,” says half-Spanish, half-Irish Thompson, who grew up hearing stories from his Spanish grandmother about the communal oven and social space in her rural town.

Mostafa Latesh, an ex-fighter in Tripoli, was radicalised until he started painting the front lines of the conflict area in Tripoli, as well as the old weapons depot and staircases. Latesh now works full-time with The Great Oven in Beirut, and Shrine says he had never seen someone so naturally gifted at both art and cooking. And he’s just one of many success stories.

“It’s an example of what people can do when given a chance, and of how food can inspire art and vice versa,” Thompson says.

Rising above Covid-19 and other calamities

About a year ago, as protests began to unfold in the capital, Thompson and his business partner, Nour Matraji, decided to move the oven to Beirut. He asked a friend who owned the nightclub Ballroom Blitz if he could use it during the day as a kitchen, and brought in international DJs to play as dozens of volunteers cooked for Syrian and Palestinian refugee camps. Much like in Tripoli, the oven became a safe space and a social movement. When the coronavirus came along, the oven was moved to a Syrian refugee camp, where a volunteer named Rawda used it to feed hundreds of people.

Then August 4 dawned, and the explosion at Beirut's port caused nearly 200 deaths and thousands of injuries, destroyed neighbourhoods and homes, displaced more than 300,000 people, and brought about a surge in the need for nutrition – more than half the country currently has trouble putting enough food on the table.

Rawda cooked 2,000 meals and drove them straight to Martyrs Square in Beirut, handing them out along with clothes collected from refugees. The oven was transported back to Beirut shortly after, to the now hollowed-out Ballroom Blitz, and Thompson realised the project could do more good with more ovens.

Now there are four, but he's hoping for 10 by the end of the year. One of the new ovens is built by the Armenian community in Beirut, another by a Palestinian refugee named Bilal for the Shatila refugee camp. Finding materials can be a challenge, especially as costs are "astronomical" because of inflation, but once Thompson has the brick, steel or iron needed, he works with Bilal and other builders, as well as local and international artists, to create an oven that is also a piece of public art.

Sourcing food is another challenge. The Great Oven receives supplies from the Lebanese Food Bank, and also purchases ingredients from markets or takes donations of rotting produce from farms, which it turns into delicious meals thanks to the culinary expertise of Thompson and others.

As they roll out more equipment, the team has a programme of sorts that recipients of each oven follow. First, they receive fully prepared meals to reheat in their ovens and hand out and, as they gain expertise, they’re transitioned to cook themselves. Nation Station, for instance, a gas station-turned food distribution centre, makes about 350 meals per day and distributes 195 of these to families in the area.

Josephine Abou Abdo, a food designer who is one of the five co-founders of Nation Station, manages the kitchen and oven, which was put in the car wash section of the gas station. “The idea is to sustain the community and food security in the area,” she says. “We are also involving people in the process. It’s not just an oven for one, but for the whole community. People walking by ask what we’re doing, or how they can help.”

Abou Abdo and The Great Oven team are creative with what they cook, from roasted vegetables and kibbeh to zaatar macaroni and cheese.

'Charity can still come out of this place'

As winter approaches, and the aid and media attention after the Beirut blast slows down, the team are seeking wider support. Online donation pages have been launched, and Thompson encourages anyone to bring donations in person, especially as funds are difficult to withdraw from local banks. Visitors can come with him to the market where they can purchase food, then go watch the oven in action while listening to live music. People can also sponsor an oven for $10,000.

So far, Thompson’s had interest from restaurants in London and large charities who want to brand the ovens in their name. Sponsors can pick an artist to paint their oven, and also choose where it should go based on a cause that's important to them. For example, an upcoming gadget will go to migrant workers and another to a hospital that offers mental health services.

The Great Oven is in talks with the Norwegian Refugee Council about starting an oven in Venezuela, where there are similarities between radicalised youth and ex-cartel members, and Thompson hopes to expand in other international locations as well.

“This is an amazing thing Lebanon can gift to the world,” he says. “The Lebanese people inspired the journey of this oven, and when it goes international, they can say: ‘Look what we managed to do at time when our government had abandoned us. At our lowest point, charity can still come out of this place to help other people.’”