With a frenzy of neon lights, the smell of sizzling meats, the slapping sounds of kneaded dough and shouted orders from cars, Al Yahar Street is an assault on the senses.

And you will need all of them, too, when navigating the near two-kilometre strip in Khalidiya. Comprised of narrow walking paths dominated by residents, customers and staff whooshing by with trays of hot tea, the street is not for the faint-hearted. It is loud, raucous and filled with the colourful and cosmopolitan characters that make up the capital.

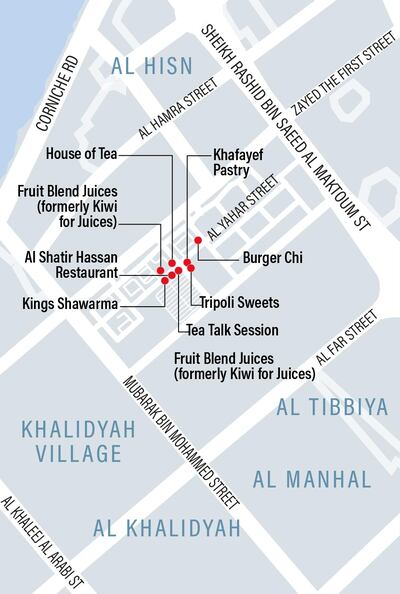

Located off Airport Road, Al Yahar Street is part of an area known as Darat Al Miyah, named after the water authority government department formerly based in the neighbourhood decades ago.

It is also the backbone of the capital's street-food scene, bringing together a diverse mix of restaurateurs who, rather than jostle for customers, have created their own, wholesome ecosystem – even supporting those new to the area.

'Once they taste our food, they will come back'

When Maen Al Shoumari accepted the role of manager at Al Shater Hassan restaurant, he hit the ground running.

He poached experienced shawarma-makers and grill kings from leading Abu Dhabi establishments and dressed them up in snazzy green uniforms. He also decked the place out with comfortable leather chairs, sturdy dining tables and assorted plants. Even the washroom has the feel of a high-end restaurant, with warm colours and modern finishes.

Despite all that effort, the Lebanese eatery, which has been open for less than a month, is not doing as well as expected.

Al Shater Hassan is the fifth business in as many years to set up in what residents call "the silver building". From the mid-range fashion store to the Turkish, Syrian and two Lebanese restaurants, none of them made it through their first year. This is despite these ventures, according to people on the street, doing a respectable trade.

This is why the site is labelled "manhoos". Translated as unfortunate or unlucky, it can mean the kiss of death for any establishment.

Al Shoumari, dressed in a sharp grey suit, knows what he is up against.

“I have faith and patience. I don’t believe in such superstitions,” he says. “Normally, a restaurant like ours needs six months to get on its feet. Getting the first wave of customers can be the hardest, but once they taste our food, I guarantee you they will come back.”

A street where success is ultimately shared

This is not bullish confidence, but an example of a collaborative belief that sustains one of the most vibrant and competitive food hubs in the capital.

Al Shater Hassan's arrival is the main news among the street's traders. That it was not met with ridicule owes as much to a fraternal spirit as good business sense.

“Listen, bro, that place is manhoos but we wish them all the best,” says Mohammed Al Ayoubi from Tripoli Sweets. A mainstay of the street for two decades, the shop specialises in northern Lebanese desserts and commands a loyal fan base for its sweet cheese rolls known as halawet el jibn.

“The thing with this street is that everyone benefits together. It is in my interest for his shop to do well because it brings more people to the area, and that’s the same with what we do here with Tripoli Sweets. We all work hard to make our businesses work but, at the same time, the success is also shared.”

That, of course, is providing everybody pulls their weight.

Al Ayoubi has seen many businesses perish for reasons that have nothing to do with bad luck.

“It’s down to a lack of respect,” he says. “Some people come here and think because we are not in an expensive area, they can serve customers bad food. They hire anybody to cook and think people won’t notice.

"The customers here are proud, they have great taste and if you treat them with respect and serve quality food, they will be loyal. They will be your ambassadors and tell their friends.”

That principle is what has allowed Kings Shawarma to achieve the status befitting its name. Located beside the Dar Abu Dhabi coffee shop, the Syrian restaurant is so popular that residents use it as a landmark for delivery drivers from other restaurants.

It won its crown thanks to its expertly marinated chicken and lamb dishes, normally served with saj bread. The most popular plate is the Dh23 Arab Box, a hearty meal comprising juicy shavings of chicken or lamb shawarma, cottage fries, an assortment of pickles and spicy garlic sauce.

“Normally we use 80 kilograms of meat – that’s both chicken and lamb – from lunch to closing time. But on weekends, we get through 90kg,” says Lebanese chef Abu Abeidan. “It is almost like a partnership with the patrons. We will always do our job in serving fresh, delicious and clean food, and they come with their family and friends. You need to have faith and confidence that things will go well.”

The crazy noodles with Cheetos

But surely there is a fine line between confidence and recklessness, right?

It is a question Indian restaurateur Noufal Kuriya was asked repeatedly when opening his quirky cafeteria Tea Talk Session in March. Positioned directly across the street from the popular House of Tea restaurant, the perception among the public was that Kuriya’s joint would shut its doors within weeks. Nine months later, Tea Talk Session still stands with a cult following of its own.

“The first week, everyone asked me if I was crazy, opening next to House of Tea. They said I had no understanding of the street and I was silly,” Kuriya says. “This is the opposite. I studied this street for months and I realise that people here like variety.”

Kuriya did that by capitalising on what House of Tea didn't do. If they served karak, a milky tea, using condensed milk, he would use fresh milk. If their parathas had the usual fillings of egg, mincemeat and tandoori chicken, he would up the ante by incorporating halloumi, fresh veggies and crumbed chicken strips.

If House of Tea used Chips Oman to garnish dishes, Tea Talk Session would use Cheetos. The latter resulted in the bestselling Cheetos Noodles dish. At Dh7, this quick snack consists of noodles whisked with Kraft cheese spread, which sit below a mountain of Cheetos crumbs. While it looks dubious, it is delicious due to the complementary textures of crunch and cream.

"You see?" Kuriya says at my surprised reaction. "I am not crazy. Everybody on this street knows what they are doing. There is plenty of food for everyone. Just come hungry and you will find what you want."

Fancy a juice called The Terminator?

What if you are thirsty?

Seeing the endless stream of restaurants, Syria’s Moanes Riffai sensed people could use a refreshing drink after a heavy meal. Hence his colourful store, Fruit Blend Juices, is a favourite takeaway spot late at night.

“The great thing about fruit is that it transcends culture,” he says. “You may not like kebabs or parathas, but everyone likes a fruit juice.”

And there is an art to it, too.

Some of the wild-sounding mocktails served – including the pre-pandemic Antivirus Juice (lemon, mint, ginger), Wishes (mango, avocado, ice cream and milk) and The Terminator (mango, banana, date and ice cream) – come from hours of experimentation. And sometimes, as in the case of his bestselling Avocado Shake, they are born from customers' suggestions.

"The avocado juice came from my Filipino friends," he says. "Before, I would mix it with banana and that's it. Then one person told me to add honey to it because in the Philippines it is very expensive. By doing that, many Filipinos came here to get the juice because it was affordable."

Heart and soul on a plate

From sampling the gut-busting sandwiches at Burger Chi to digging into a plate of Egyptian street-food staple koshari at Khafayef Pastry, spending an evening among the honest chefs and restaurateurs that line Al Yahar Street is both mind and waist expanding.

Their resilience and determination to bounce back amid the pandemic, through hard work, zeal and a generous spirit, is heartening and inspiring. That said, the street can always use a little bit of help from further-flung patrons.

“Everyone who knows their street food understands this area is the place to go, but the only people I see here live close by," says Al Shoumari.

"This place should definitely be on the tourist trail because you will really see the spirit of Abu Dhabi here. There is too much focus on high-end dining, in my opinion, and not food that is simple and honest.”

As the clock approaches midnight, Al Ayoubi prepares to serve the last batch of Lebanese harissa to a couple of late sweet-toothed customers.

“You know how many times I have been offered to open up a shop in other emirates or fancier parts of this city?” he says. “I always say no. I love my customers here and this place. We may not have high rises, but there is kindness and heart here in this street. And delicious food, as well. Tell me, why should I leave?”