When John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich, asked his chef to prepare sliced meat between two pieces of bread in the mid-1700s, he could not have imagined the culinary fame he was signing up for.

However, the Encyclopedia of Food and Culture notes the practice of serving “delicate finger food” between two slices of bread dates back even further. Montagu likely came across the stuffed pitta breads and small canapes served by the Greeks and Turks during his excursions to the Eastern Mediterranean. He copied the concept and unwittingly tied this genre of food with his title.

According to Mark Morton, co-author of Cooking with Shakespeare, before the term sandwich came about, this food was simply called bread and meat or bread and cheese. In a 2004 article in food journal Gastronomica, Morton bolsters his argument by saying that such references appear in English drama written in the 16th and 17th centuries. He writes: “Shakespeare uses the phrase in The Merry Wives of Windsor, where Nim announces: ‘I love not the humour of bread and cheese.’”

While Morton is not incorrect, the sandwich timeline begins well before the Bard’s time – at least in the Middle East. The earliest documented example dates back to the first century BC, according to the book Sandwich: A Global History.

Author Bee Wilson notes the scholar Hillel the Elder created the custom of eating sacrificial lamb and bitter herbs sandwiched together inside unleavened (matzo) bread. This “sandwich” was akin to a roast lamb and herb wrap similar to a kebab, writes Wilson, and “probably very delicious”. The fact Hillel recommended eating the meat, herbs and bread together in this way suggests that “sandwiches” of this kind had been on the menu in the Middle East for a long time.

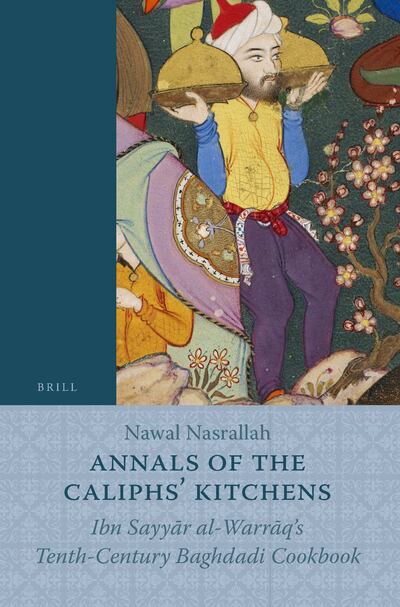

“Recipes for sandwiches in Medieval Arab cookbooks have more than one category name depending on how they were made, and we can see an impressive list in these cookbooks,” food historian Nawal Nasrallah tells The National.

“During the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt, between the 10th and 12th centuries, sandwiches were conveniently offered in large trays to the public to celebrate the end of Ramadan, both to eat and to take home. As fast food, sandwiches were cheaply purchased from the cookshops in the food markets.”

She adds that depictions of bread rolls as well as two layers of bread with fillings in between have been seen on Ancient Egyptian temple walls and Mesopotamian cylinder seals. Evidence exists that in ancient Mesopotamia, more than 300 varieties of breads were baked, says Nasrallah, pointing out that the “consumption of sandwiches goes hand in hand with bread-making”, and that it was likely that sandwiches were popular because of how convenient they are to eat.

Historian Daniel L Newman is working on a book tentatively titled Categories of Foodstuffs – which contains previously unknown Abbasid culinary and pharmacological traditions – of which sandwich recipes are a part.

“There are several examples of what we now call sandwiches from Abbasid times,” confirms Newman. “The cookery books that contain recipes of such foods were written between the ninth and 13th centuries, and came from Iraq, Syria and Egypt.”

Books from the Abbasid era categorise sandwiches as part of a long list of cold and dry dishes, which were served before the main hot meal. The small portions were passed around in trays much like today’s hors d’oeuvres.

The earliest known Arabic cookbook, Ibn Sayyar Al Warraq’s 10th-century Kitab at-Tabikh proffers five recipes for three types: Pinwheel, closed and open sandwiches.

Among the pinwheel variety is bazmaward. The Baghdadi style calls for spreading uncooked meat, boiled eggs and seasoning on flat bread, and baking it in a domed clay oven called tannur before slicing finely. The two others are named after caliphs Mamun and Mutawakkil, and are made by spreading cooked meat, vegetables and condiments on flat bread before rolling and slicing it.

Wast, meanwhile, refers to filled sandwiches in which thick bread is stuffed with meat, vegetables and cheese, then sliced into strips or triangles.

The recipe for the open-faced sandwich is called wast mashtour, which was made by Abbasid prince and cookbook author Ibrahim bin Al Mahdi. It comes with a poem he wrote: “What a delicious sandwich on the brazier I made / Fragrant and shining / Smeared with egg yolk, with cheese sprinkled, like speckled embroidered silk / As colourful as striped silk it looks.”

Al Warraq’s cookbook, translated into English by Nasrallah and titled Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens, also contains information on the humoral properties of these early sandwiches – both the rolled-up and pressed variations are slow to digest and best eaten at the beginning of the meal.

In an eighth-century medieval Arabic book on the interpretation of dreams, meanwhile, an entry relating to food mentions that dreaming about bazmaward foretells a good life with plenty of easy money.

The appeal of sandwiches has not faded, but their medieval names have, says Nasrallah.

“They are known by different names across the Arab world today, Shata’ir is the official name in standard Arabic, while in Iraq, laffa denotes both wraps and stuffed, hollowed-out brick-oven bread.

“In the Levant, arayes sandwiches are none other than the bazmaward and awsat of medieval times,” explains Nasrallah, adding that the art of making sandwiches as recorded in age-old Arab cookbooks helps connect the dots in the evolution of the world’s most popular finger food.