Majlis Al Jinn in Oman is the ninth largest natural underground space in existence. Eugene Harman joins a team of cavers to explore a world of wonder under the earth's surface, one that was formed millions of years ago - and is in need of a good clean-up.

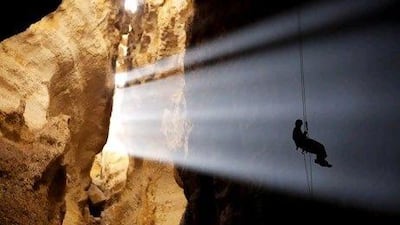

Like a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark, a beam of light cuts across the cave's chamber. It begins in the Asterisk Hole in one corner, and catches a climber by surprise when he drops down. The beam takes 20 minutes to reach the other side of the chamber before it fizzles out. Unlike in the film, here in Majlis Al Jinn in Oman - the ninth largest cave chamber in the world - it reveals no miniature city or the exact location of the Well of Souls.

The ancient chamber, whose names means "meeting place of the jinns", was discovered in 1983 by Americans Don Davison and his wife, Cheryl Jones, who had Cheryl's Drop named after her because she was the first to go down that hole. They were hired by the Omani government to map the regional cave and water systems on the plateau. Only a handful of teams have descended the chamber since then, and the Middle East Caving Expeditionary Team (MECET) has been invited - on a rare occasion - to clean up the cave on the Selma Plateau, 100km south-east from Muscat.

It is the moment we train for, but nothing can replicate sitting in a tight harness 180 metres above ground. When I descend and the voices fade from above along with the morning sunshine, I look down through the cool limestone chimney and can make out a light, sandy bottom.

Before I can zip slowly down the line, 10 members of MECET drop down before me and another six are to follow - the first in darkness at 5am guided only by head torches.

I hook in my ASAP safety device to the second rope, dubbed the safety rope, and am checked by one of the crew. If the working rope broke when I was suspended anywhere between 180 metres and five metres, this chunk of metal and wheels would lock onto the rope and save me from a sudden fall to inevitable injury or death.

Then I feed the working rope through the descender device and peer over the edge. Below is darkness. A shaft about three metres wide drops about 20 meters before the chamber opens.

Officials halted permission to enter the cave in 2007 after a BASE jumper - a daredevil who parachutes, often illegally, from buildings, antennas, spans and earth (cliffs) - successfully took the plunge in through the wider hole called the First Drop. Before I take to the ledge, I have to put all my faith in the gear, but it doesn't feel right. The working rope is not naturally hanging to the right of my descender. Instead it is sticking up and twisted.

Before a drop of five meters or more, safety

checks are imperative and this one finds the descender upside down.

It takes another five minutes before I am able to walk off the lip. I finally get past the deviation point where the rope is fed through two carabiners so it won't rub against the rock and snap.

It is an easy manoeuvre in a training environment, but the weight of 200 metres of rope and dangling 158m makes it more difficult to lift through the carabiners and move the gear. One wrong move and I'd be one step closer to the same fate as that of the goats that got too close to the edge.

The radio from above crackles to the team below and tells them I am on my way down. The final shudder of paranoia and fear is dispelled once I start to walk down the face of the drop with all my weight in the harness. The voices fade away and I am left staring at rock alone.

The silence is broken by the sound of the rope zipping though the descender. The deeper I go the darker it gets. Below me, I can see a bright, light, sandy bottom. A few more metres down the chimney, the chamber opens up. I lock the descender onto the safety lock and hang there to take in the view.

The cavern opens up into a wide chamber - approximately 4,000 cubic metres of space, or big enough to hold one of the pyramids of Giza or skyscrapers of Dubai.

John Gregory was one of the first to drop, in barely any light. "I was just trying to observe the fact we were in a great big cave and I was just suspended there so high up from the ceiling only by a rope," he says.

Gregory, 69, who usually spends his weekends climbing some of Ras Al Khaimah's most challenging rock faces, says it was an unusual experience. "When abseiling off a cliff, your feet are always against the rock, but on this you are just hanging and swing a little bit," he says.

Will Hardie, 33, says the experience is more like a dream.

"The cave opened up so fast it was breathtaking," he says. "One moment you are inching down a narrow cleft and the next, there you are dangling in this indescribably huge open space. The first thing that struck me was the sheer distance down below my feet. The people and details down there were so tiny and far away. It felt like looking out of an airplane at a landscape."

Nicky Vanlommel, 33, an experienced Belgian caver, says the most memorable part was the colours.

"I was amazed by the space and how wide it was," he says. "You know it's big when you go in and it's only when you're at the ceiling and look down and see the orange and brown scene below you [that you appreciate it]. It was a very special atmosphere. It was like it brought me back in time or to another world. The atmosphere is so completely different."

Reinhard Siegl of the Oman Ministry of Tourism says the cave was formed 34 million to 56 millions years ago, during the Eocene Epoch, and is characterised by thick beds of massive fossiliferous pale yellow limestone. Floods carved out the floor, he says, and dripping water from the ceiling created stalagmites.

Another caver on the team, Gavin Cassidy, a broadcasting bid manager from Northern Ireland, says it was surreal watching others drop down after he had made his descent. "Being on the bottom and seeing someone else abseiling and see how tiny they were. If you did't know where to look on the rope you could hardly see the person," he says.

The cave floor is mainly barren, expect for a few small animal tracks, flags from previous expeditions (Lebanese, French, British and US among them) and several blue plastic bags, apparently blown in by the wind. The team removes the bags.

"It was a complicated operation. Seventeen people had to go down one set of ropes and get back up on two sets in a limited amount of time safely. The real satisfying thing was everyone was out safe and we achieved what we had to achieve," says Hardie.