All the money Ram Pyari Anand, a widow living in Sialkot in pre-Independent India, possessed was saved in the Bank of Sialkot. When the 1947 partition created a separate Pakistan, which Sialkot became part of, the Hindu mother of four daughters fled the country with only a small bundle of possessions, including her bank passbook.

Today, 76 years after India and Pakistan came into being, that passbook is one of many exhibits at the recently opened Partition Museum in Delhi.

Inaugurated on the Ambedkar University campus in Kashmere Gate in May, and housed in a 17th-century heritage building, the museum and its accompanying Dara Shukoh Library Cultural Hub is a walk back into a tumultuous time in history.

The 1947 partition was the result of a border drawn in a rather ad hoc manner within a matter of merely five weeks. Its result? The largest mass migration in history.

The museum showcases the story of the partition of one country into two, as well as audio recordings of Delhi residents speaking about how India’s capital city changed owing to migration and resettlement.

For instance, a clip by Kuldip Nayar, a renowned journalist whose family migrated from Pakistan to Delhi, features an interview with Cyril Radcliffe. It was this British lawyer who demarcated the border, etching the so-called Radcliffe Line, which separated the two countries. “I had no alternative. If I had two to three years, I may have improved on what I did,” Radcliffe admits in the clip.

Visitors can listen to this and other recordings of people who witnessed the partition first-hand, through screens and headsets placed across the museum’s seven galleries. These start with the events leading up to the partition, and the aftermath of the event.

Artefacts include newspaper clippings, sculptures, art installations, documents and memorabilia such as letters, postcards, wedding cards and Urdu books, each telling the evocative stories of people uprooted overnight.

Tragic beginnings

The foyer of the museum is dominated by Kashmiri sculptor Veer Munshi’s papier-mache horse, which is loaded with human skeletons and bones, or “the weight of the Partition”, representing the tragic fate of tens of thousands of people forced to abandon their homes.

Death is a dominant theme in the first few sections. In the second gallery, for example, set against a backdrop of haunting music, is a train coach with wooden seats. This harks back to the time when people fleeing the riots and violence that rocked both countries took trains only for their relatives to witness carriages arriving full of dead bodies, belongings strewn across the compartments in mute testimony to the tragedy.

Another section displays hard-hitting photographs, of corpses left abandoned at railway stations and bodies lying on carts, as well as people, especially women and children, who suffered rape, robbery and starvation.

Refugee crisis

As people moved between the countries, it was estimated that the population of Delhi alone nearly doubled from 900,000 in 1947 to 1.74 million as per the 1951 census.

Several sections of the Partition Museum represent the refugee crisis, with one space fashioned to resemble a tent akin to that of a refugee camp, with exhibits such as ration cards and joint India-Pakistan passports.

Camps aside, many large monuments such as Humayun’s Tomb served as temporary accommodation, while squatter colonies also developed, with many living on railway platforms and empty plots.

The rise in population in Delhi laid the foundation of Punjabi Bagh by then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who told residents to not call themselves refugees, but “Punjabis of Punjabi Bagh”. Many other popular areas in the capital, including Lajpat Nagar and Faridabad, too, originally sprang up as refugee colonies.

The exhibits here are basic, but all the more heart-rending for it – from a lock used to secure the trunk carrying one family’s meagre belongings, to entire wooden bed posts carried across the border by another; and from a vintage Singer sewing machine to a piece of cloth with embroidery work in Sindhi, the language spoken by the predominantly Hindu community of the same name, who lived in Sindh (now in Pakistan) before the partition.

Silver lining of hope

The human spirit of the refugees, once they had settled, is also highlighted in the museum. One section is devoted to how the refugees brought with them traces of their own culture, food and language, and their effect on the literature, music and films of India. The partition famously led to an outpouring of literature and poetry related to the cataclysmic event.

There are also feel-good stories, such as that of Savita Batra who migrated from Pakistan with the beloved sitar she had watched her father play. Batra wanted to learn how to play the instrument and began her search for Rikhi Ram, whose name was inscribed on the sitar. As luck would have it, Ram had set up a shop in Delhi’s Connaught Place and recognised his craftsmanship immediately. The sitar went on to become a family heirloom, which has now been donated by the Batra family to the Partition Museum.

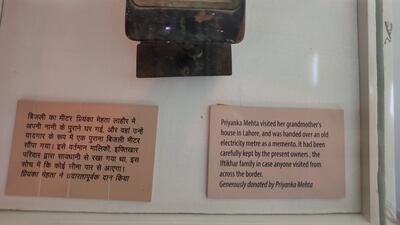

Elsewhere, we learn of Priyanka Mehta, who visited Lahore post-partition and was handed over an electric meter that belonged to her family, by the Iftikars, the new owners living in her ancestral home.

From stories of the courageous people who rebuilt their lives from scratch to those who came to helm successful business, many of which still exist, the museum has plenty of feel-good narratives.

The partition was a tragedy that affected not just one generation, but rather left its imprint on the lives of many. However, above all, the museum records stories of hope and courage that celebrate the triumph of the human spirit, which can rebuild and move on even after the greatest of misfortunes.

As a song playing on loop in one of the galleries notes: Tu Hindu Banega, na Musalmaan Banega, Insaan ki Aulaad hai, Insaan Banega (You will become neither Hindu nor Muslim. You are the child of a human being, and humane is all you will become).