As the parliament building in the South African city of Cape Town burnt on Sunday, the Keiskamma Trust waited to learn the fate of its tapestry that hangs inside the building.

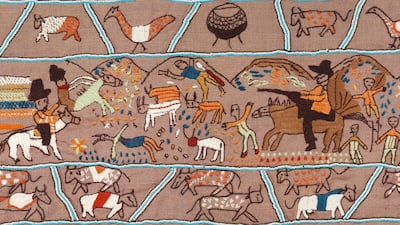

Stretching 120 metres, and entirely made by hand by the Xhosa women of Hamburg, a remote south-eastern region of South Africa, the Keiskamma Tapestry tells their unique, and often painful, history covering the arrival of the colonialists in 1820, through oppression and apartheid, to the release of Nelson Mandela from jail in 1990.

Completed in 2004, it took its inspiration from the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry in France, which depicts the conquest of England by William, Duke of Normandy, in 1066. Similar to the original, the Keiskamma Tapestry is also misnamed, as it was hand-stitched rather than woven, but it was named after the river that runs through the Eastern Cape.

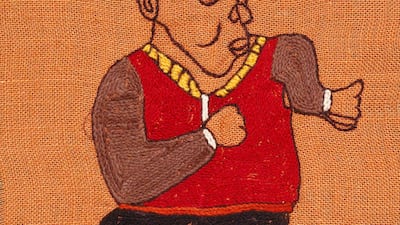

The Keiskamma Trust was set up in 2000 to help the impoverished Xhosa people living along the river. It was founded by Carol Hofmeyr, a doctor and artist who had moved the region to retire. Struck by the level of poverty and hardship in the area, she set up embroidery classes to help the women earn a modest income, which grew into a wider project. The women began using the embroidery for telling their personal and collective histories.

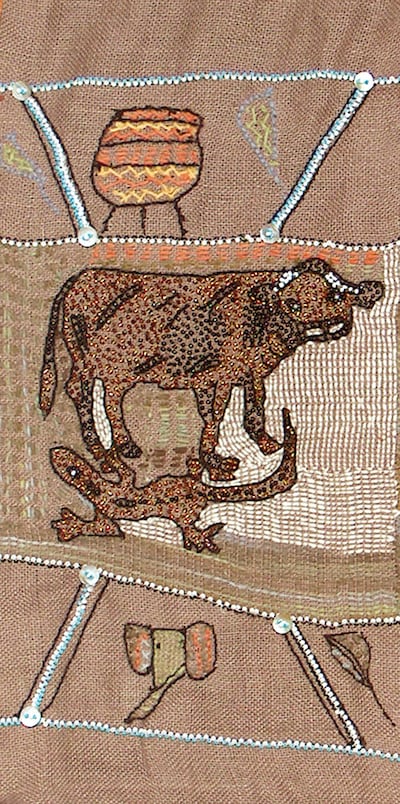

Having seen the Bayeux Tapestry in France, Hofmeyr realised its expansive, cartoon-like, running narrative was the perfect medium for the women to document their stories. Working on a background of Hessian food sack, stitched together and dyed with red ochre, more than 100 women spent a year working on the piece using traditional patterning, colours and even beading.

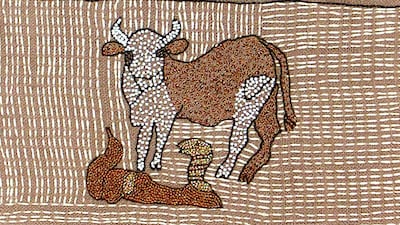

Once finished, the panels were combined to create a single, continuous story that stretches over 120 metres. It depicts the everyday life of Xhosa cattle farmers and the Nguni cow, considered the heart and soul of the community. It tells of the unending quest for new grazing, and how the arrival of certain birds signalled the shift of seasons, prompting planting and harvests of sorghum, maize and pumpkin.

It shows the arrival of the colonialists in 1820, bringing guns, violence and evictions as they upended traditional lifestyles. It tells of the invading British and Dutch slaughtering the Xhosa, San and Khoi people, and the relentless land grabs of the Europeans as they moved north. It depicts the “cattle killing” of 1856 to 1858, when the new diseases brought by the invaders and their animals all but wiped out the Xhosa cattle.

Captured in stitch, the tapestry shows the European soldiers using rifles against unarmed farmers and unflinchingly captures the horror of invasion, eviction and oppression through decades of apartheid.

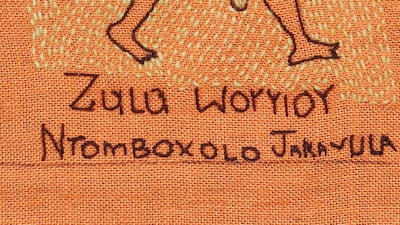

Each panel was worked on by one or two women, and each woman has added her name to the work, making it a uniquely personal account of history.

History is usually told by the victor, yet here, it is the silenced who have been given a voice.

In recognition of its cultural worth, once finished, the tapestry was hung inside the parliament building, where now, ironically, it faces destruction or damage. Deemed safe after the first fire, a second blaze sparked by the smouldering wreckage means the work is once again in danger, unable to be rescued. If the tapestry has survived the flames, it remains to be seen if it has sustained smoke and water damage.

However, if the fire is to serve one purpose, it is to bring this little-known work to light. For years hidden from view in the dim corridors of government, if this unique and irreplaceable work does emerge from the ruined building unscathed, perhaps it will prompt the powers that be to display it properly.

Like the Bayeux that inspired it, the Keiskamma Tapestry deserves a dedicated museum so everyone can savour the brilliance of this very modern masterpiece.