Driving down the national highway from Srinagar to Pahalgam, past snow-covered peaks, saffron fields and army checkpoints, you come across Sangam. This sleepy village, located about 40 kilometres from Srinagar, greets you with grids of willow clefts stacked along the roadside and on roofs of buildings, and left to dry under the mellow Kashmiri sun.

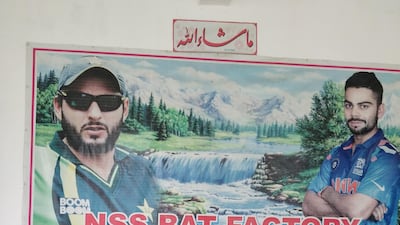

Sangam’s claim to fame is its cricket bats, which find their way into the kits of aspiring and famous batsmen, as well as being used in gully cricket in billions of bylanes all over India. Gargantuan hoardings and advertisements of famous cricketers festoon the fronts of the shops lining the highway; within are neatly stacked rows of bats with colourful grips, emblazoned with logos from MRF, to Reebok and Adidas.

The willow trees that are used for making these bats have been a part of this landscape for millennia, but it was only in the 19th century that forest department officials Walter R Lawrence and JV MacDonell began encouraging the development of large willow tree plantations.

Colonisation may have brought cricket to the subcontinent, but the game continued to be popular even after India attained independence in 1947. The 1980s and 1990s clocked something of a cricketing frenzy, and this was when the cricket bat industry got a huge fillip, as well as again following the 2011 World Cup victory. Famous cricketers including Sachin Tendulkar and Vivian Richards have played with Kashmiri willow bats.

owner, NSS Cricket Bat Factory

More than 300 families and 10,000 people are employed in this industry in Sangam and its neighbouring villages. Nearly 90 per cent of cricket bats in India are made from Kashmiri willow and the country is estimated to produce more than 500,000 bats every year.

Kashmiri willow bats are priced from a mere 200 Indian rupees ($2.67) up to 3,500 Indian rupees, which is much cheaper compared with English willow bats that can cost as much as 30,000 Indian rupees because of their higher grain density.

“Willow from England is regarded as supreme in quality, whereas willow bats from Kashmir come at cheaper prices and are heavier, too. But play with a bat from here and you will never want another,” says Nayeem Hussain Dar of NSS Bat Factory, which was set up in 1980.

Dar, who is a talented cricketer himself and has played for various clubs in the valley, says the unit was started by his father, Mohammad Amin Dar, and employs 20 workers who make more than 1,000 bats every month. “Each worker can make between 30 and 50 bats a day,” says Dar.

“The process starts with sourcing willow wood from the forests surrounding Anantnag, from trees that are about 15 years old and have a girth of more than 34 inches. The more circles on the trunk, the older and stronger the tree is. The wood is then cut into blocks or bat-sized chunks called clefts, and left in stacks to dry under the sun for up to six months so it loses its moisture, and becomes hard and durable,” he explains.

The blocks are then chiselled, hewn, hammered and cut into shape using sandpaper and small lathe machines. I watch as a worker patiently shears layers off a piece of wood, sitting on a dirt floor covered by confetti-like sawdust and splinters, as he gets the desired weight of the bat. He looks with pride at the piece of wood, and evens out all the bumps until the clump looks more and more like a cricket bat. Bats in different stages of manufacture lie on the floor in front of other workers – some are just a sticker or grip away from the cricket stadium.

A cleft of willow passes through as many as 30 stages, from lamination by dipping in a furnace to polishing, before it becomes a fine cricket bat. The handle is painstakingly cut from the log or sometimes from cane, attached to the bat and then sent for compression and oiling.

Winter is when the demand for bats is at its peak as more people want to play outside in cooler weather. However, the plantations have suffered from problems of civil strife and insurgency in Kashmir as well as irregular power supply.

Many manufacturers have switched to poplar wood, which is cheaper and takes only three years to mature (a willow tree takes between 20 and 30 years), but the wood is simply not the same quality, says Dar.

In a country where cricket is like a religion, bats are obviously prized commodities, but the industry needs sustenance. “We have to pay a GST [sales tax] and that adds to my costs. If we get a geographical indication that certifies the bats originate only in this territory, it will help us to market our bats and be competitive in the domestic and international market,” says Dar.

After all, despite the various tech-infused bats – with sensors and carbon-fibre-reinforced polymer – it is the ones made from Kashmiri willow that still hold the imagination of cricketers from India and all over the world.