Amani Alshehhi’s fascination with Japanese culture “goes way back”.

“My earliest memories of Japanese culture is through the souvenirs my father would bring back from Japan when I was a child. Some of them were intended for my mother, but it wasn’t long before I took over them and had a little ‘Japanese corner’ in my room, filled with things like pictures, ceramics and souvenir kimonos,” she says, with a laugh. “It was all so colourful and beautiful. It felt like another world.”

This fascination only grew as she got older and discovered Japanese pop culture and anime. So when Alshehhi enrolled as a student at Zayed University in Dubai, it was only natural that she gravitate towards the university’s Japan Club, which often held events and hosted students from Japan. It was at one such event that she would meet Harue Oki, an ikebana professor who was doing a demonstration on the Japanese art of flower arrangement.

Alshehhi was hooked. “It was amazing, the way she arranged the flowers. It has structure, rules, architecture. I knew I had to get into it,” she says.

What is ikebana?

Ikebana, also known as kado or “the way of the flower”, is a Japanese form of flower arrangement known for its characteristic minimalist, sparse appearance.

A far cry from most floral arrangements that have flowers packed in together, ikebana operates on the assumption that less is more, and that by reducing the number of elements in an arrangement of flowers, you can truly appreciate the beauty and appearance of every bloom, leaf and stem.

It is one of the practices considered a Japanese “do” or “way of living”. As Alshehhi describes it: “It’s all about creating a living sculpture.”

Scroll through the gallery above for examples of ikebana arrangements.

Enraptured by the beauty of the art form, Alshehhi signed up at the Ohara School of Ikebana in 2015. Classes are conducted in both Dubai and Abu Dhabi by Oki, and while it started out slow – with only one class a week – it wasn’t all roses.

“I know it sounds weird to use the term ‘challenging’ with flower arrangements, but as you advance that’s how it gets,” says Alshehhi, who has completed 120 classes to date to get her instructor qualification.

“At the beginner’s level, you learn two basic styles and keep practising until you’ve perfected them. These then form the basis for the more advanced formations.”

Over the course of five years, Alshehhi completed five levels of classes – beginners, advanced, assistant teacher’s level 1, assistant teacher’s level 2 and finally the instructor level – after which she received the ikebana name Misaki, which means “beautiful bloom”. The certification is the first step, with the highest recognition possible being First Master of Ikebana.

“Amani is especially proficient in moribana, a style of flower arrangement invented in the Meiji era [between 1868 and 1912] when western flowers started becoming popular in Japan,” says her teacher Oki. “It’s a bit more relaxed, the flowers are not always standing up, they are facing forward.”

Life lessons from Japanese flower arrangements

The concept of ikebana begins with three principal stems – be it flowers, branches or leaves – and there are rules for the lengths, heights and angle of each of these. Once they have been arranged, the florist will add flowers and can use their own creativity to achieve the required look.

“You might think that because there are a set of rules, all ikebana arrangements look the same, but that’s not the case at all. The individuality of the arranger shows – from the way they choose the flower to their placement of it,” says Alshehhi.

There are plenty of other takeaways from the Japanese art of flower arrangement. “The most difficult part is the minimisation process,” says Oki. “It’s not just about flower arrangement. You have to know what to subtract to highlight other parts. But, like in life, once you cut out a certain part, there is no going back. So you have to concentrate.

“There are times we get flowers or petals that look so pretty my heart hurts to cut off the smaller petals,” says Alshehhi. “But I need to minimise to bring attention to another part of the stem. It’s about making hard decisions.”

Ikebana workshops in Arabic

It’s all worth the effort, though, not only because of the delicate final outcome, but because of the process involved, which Alshehhi describes as therapeutic.

“My favourite thing about ikebana is observing the beauty of the flowers – the leaves, the curves. It really gives you an eye for detail and helps you see that less is more. With ikebana, you learn to appreciate the individuality, the flaws of every flower. There are times I see big bouquets and I think it's such a pity for so many beautiful flowers to be piled on in such a way that no one can appreciate a single flower.

“Most importantly, it grounds you and connects you to nature. With the kind of lifestyle we lead, being online all the time, and the climate we have, it’s nice to have a hobby that can keep us connected to nature throughout the year,” she says.

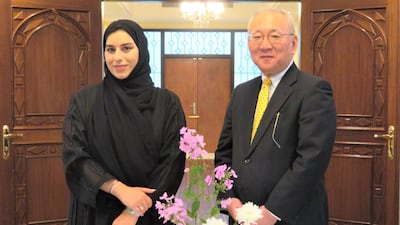

In the months to come, Alshehhi plans to start taking up workshops in the UAE so others can delve into the art of ikebana. Meanwhile, Oki is delighted to finally have an Arabic-speaking instructor. “We have gotten queries on whether we can do classes in Arabic for years now. Finally, Amani is here so she can spread the art of ikebana to this part of the world,” she says.

Which means we might be seeing more ikebana events in the region in the years to come.

“I started this journey in university with the Japan Club, where we hosted so many students, many of whom I am friends with to this day," Alshehhi says. "I hope to continue to increase the friendship between the two countries.”