Measles cases are on the rise, with surges in 2024 causing concern among health authorities in many countries.

Just this week, an urgent alert was issued after a man on a flight from Abu Dhabi to Dublin was found to have the viral disease.

Because measles is highly contagious, 95 per cent of susceptible infants have to be vaccinated to keep the disease at bay. However, fewer countries are successfully hitting this target. In the West Midlands area of England, for example, rates are little more than 80 per cent.

comunicable disease control specialist

"One case can generate between 15 and 18 new cases in an unimmunised population," Dr Bharat Pankhania, a senior clinical lecturer and specialist in communicable disease control at the University of Exeter in the UK, said.

"In some parts of the country, vaccine coverage is well below 95 per cent and has been for some time. Once the measles virus starts circulating, it will find the unimmunised and you will get the cases … We knew this would happen."

How do you catch measles?

Measles, an airborne disease spread by breathing, coughing or sneezing, usually begins with cold-like symptoms before causing a rash that affects the face and the area behind the ears and spreads to the rest of the body, according to the UK’s National Health Service.

In most cases, people start to improve after about a week, but more serious complications can develop when the disease enters the lungs or brain, leading to, for example, pneumonia, blindness or meningitis, with some cases proving fatal.

Measles during pregnancy can cause low birth weight, premature birth, miscarriage or stillbirth.

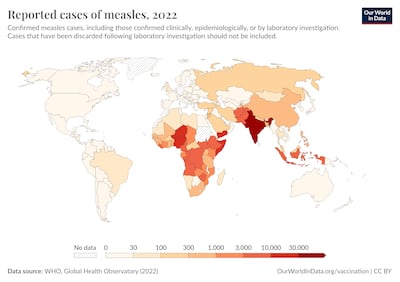

In the 41 nations that make up the World Health Organisation’s Europe region, measles cases reached 42,200 last year, which is about 45 times the number in 2022, when there were just 941 cases. About one in five cases were in people aged older than 20.

Between 2020 and 2022, 1.8 million infants in these 41 countries did not get their measles vaccination, according to the organisation.

This year, Dr Hans Kluge, the WHO’s regional director for Europe, called for "urgent vaccination efforts" to "halt transmission and prevent further spread".

The UK is among the nations where renewed efforts have been made amid alarm among health officials about the number of cases.

There are now more than 3.4 million under 16s in England alone who are not protected against measles, official figures show.

The US declared it had eliminated measles in 2000, meaning that there was no continuous transmission for more than a year – something officials credited to vaccination.

But a drop-off in vaccination rates has been seen there too, with the US experiencing a jump in cases.

Why are fewer people being vaccinated?

Several factors are thought to be responsible for the low uptake of the measles vaccine, which is typically given as the MMR jab, a triple shot that also protects against mumps and rubella.

Some doctors have said that regular vaccine programmes were disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, causing some youngsters to miss out on their injections.

Among some Muslim communities in the UK, there has also been concern that a pork derivative is included in the standard MMR jab, but an alternative with different ingredients is also offered.

As the UK’s National Health Service is widely seen as being overstretched, parents may have found it difficult to book appointments for vaccinations or there may have been a lack of follow-up by the service, Dr Andrew Freedman, an infectious diseases specialist at Cardiff University in Wales, said.

"It may not just be people deliberately making a decision not to give their children MMR," he said.

Typically given in two doses, the first at about 12 to 15 months, the vaccination is highly effective, offering 95 per cent protection after the first dose and 99 per cent after the second. In countries where the risk of exposure is very high, the first dose may be given earlier and should be followed by two further injections.

False data

Another reason why some parents choose not to have their children vaccinated can be traced back to the late 1990s, when a now notorious scientific paper was published in the medical journal The Lancet.

This 1998 study, which has since been withdrawn, falsely suggested that there was a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

A co-author of the study was Andrew Wakefield, a medical doctor who was subsequently banned from practising medicine over dishonesty after he was found to have falsified data in the study.

While there has been scepticism since the first vaccine was developed in the late 18th century, Mr Wakefield is often seen as the chief cheerleader for the modern-day "anti-vax" movement, which has gained traction on social media and found a sympathetic ear in the former US president Donald Trump.

Dr Freedman branded the supposed link between the MMR vaccine and autism as "completely untrue", as well as other claimed associations with conditions such as bowel disorders.

"There’s no evidence. The publications were shown to be wrong," he said. "The onset [of autism symptoms] is around the time infants are given the MMR vaccine. That doesn’t mean it’s causative; it isn’t.

"MMR has shown itself to be very safe. It’s been used a huge amount."

Education about the vaccine is key

Boosting vaccination rates requires "legwork", Dr Pankhania said, with health workers needing to spend time with parents to discuss concerns they may have about vaccination.

"I used to be a consultant in communicable disease control in Bristol [in south-west England]," Dr Pankhania said.

"I used to go to mums and dads at toddlers’ groups, at the local mosque, at the local community centre. I met five, 10, 15 mums and dads to talk, advise and educate [that it would] make life better for them to do the vaccination."

Parents, now in their 20s or 30s, may never have experienced an infectious disease spreading through a population of children, so may take a chance by not getting their child vaccinated, Dr Pankhania said.

He said as well as children, adults who were not immunised should get vaccinated, including people who are unsure of their vaccination status, as a second course of shots does not cause health problems.

"Your five-year-old, your 10-year-old, your 15-year-old, your 20-year-old can catch measles and become quite ill. So … you can get the vaccine at any age," he said.