Doctors, nurses and care home staff accounted for half the visas issued to skilled workers coming to the UK over the past year, a report shows.

The study revealed the UK’s reliance on overseas health workers, which it says is at an unprecedented level in the post-Second World War era, with recruits from India making up the largest single group.

In the year ending March 2023, almost 100,000 skilled workers received visas to work in health and care jobs in the UK, a new analysis published by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford shows.

The study comes as it emerged a quarter of Australian medics are made up of NHS-trained professionals heading the other way.

Health workers coming to the UK are needed to fill 124,000 full-time job vacancies in the NHS in England, where there was a vacancy rate of 8.9 per cent as of the last quarter of 2022.

In the care sector, there was a vacancy rate of around five per cent last summer, although that has dropped this year, says the report, which was commissioned by work and employment expert group ReWAGE.

Dr Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory, said: “Health and care employers have benefited a lot from international recruitment, which has allowed the NHS to increase its workforce faster than if it was relying only on people completing domestic training.”

Broken down by nationality, a fifth of doctors, 46 per cent of nurses and 33 per cent of care workers sponsored for work visas came from India last year, the largest single group.

In 2022, 99 per cent of care workers sponsored for work visas in the UK were from non-EU countries. The top countries after India were Zimbabwe, Nigeria and the Philippines.

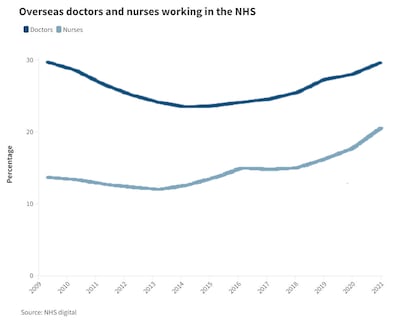

“The health and care sector has never admitted such large numbers of work visa holders as in the immediate post-pandemic period under the post-Brexit immigration system,” says the report.

“Health sector visa grants were also considerably lower during historical international recruitment periods in the 1950s to 1990s.”

But, the report warns, if heavy reliance on international recruitment continues to persist, the UK could become more vulnerable to changes in employers’ ability to recruit from abroad.

For example, Britain could be vulnerable to competition from other countries such as the US, where higher salaries are offered.

The problem of staff shortages and the strain it takes on NHS employees, as well as pay, has led to a series of strikes by doctors and nurses.

This comes as a report from the King’s Fund think tank found the NHS service is struggling to recruit locally trained staff amid “strikingly” low levels of clinical staff and nurses who had trained with the NHS.

Meanwhile data showed the percentages of British-trained healthcare workers employed overseas in New Zealand and Australia to be in the double digits.

UK-trained nurses accounted for one in five foreign-trained nurses in New Zealand and one in four in Australia.

By contrast, 1.1 per cent of foreign-trained nurses in the UK came from Australia and 0.3 per cent from New Zealand.