Read the latest updates on the Hajj pilgrimage here.

It is remarkable that as many Muslims have performed Hajj this century as the likely total number for the first thousand years of the annual pilgrimage.

About one million people will travel to Makkah this year, after two coronavirus-affected years that reduced numbers to a few thousand.

On average, about two million faithful have made the journey to the holy city from all over the world every year for Hajj in the 21st century.

Hundreds of years ago, it was a very different experience. Precise records are hard to come by, but observers speak of about 20,000 to 60,000 making the pilgrimage in medieval times and for much of the Ottoman Empire period.

For centuries, the route to Makkah was difficult and dangerous. Pilgrims would join huge caravans leaving from Cairo and Damascus, for a journey that would take weeks or even months. Travelling in a large group reduced the likelihood of being murdered or robbed by bandits and thieves who preyed on pilgrims, but it was no protection from death by disease, thirst or starvation.

Returning to Damascus in 1757, a Bedouin raid left an estimated 20,000 dead on the border with what is now Jordan. To participate in Hajj, a duty in Islam then as now, was no guarantee of returning home alive.

Even Makkah had its dangers. A cholera outbreak in 1865 is estimated to have killed 15,000 out of 90,000 pilgrims.

By the end of the 19th century, steam ships and railways were transforming the route. The Hejaz Railway was built by the Ottomans to link Istanbul with Madinah and to cement their control of the holy cities.

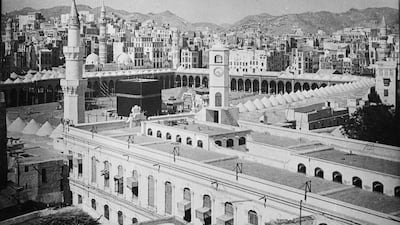

The first known photographs of Hajj were taken in 1861 by Muhammad Sadiq Bey, an Egyptian army engineer. Between 1886 and 1889 more than 250 photographs were taken by Abd Al Ghaffar, a resident of Makkah, including images of pilgrims.

First published in Germany, they show a city little changed for hundreds of years. Old houses look down from the hills on the colonnades of the Grand Mosque and the kiswa-shrouded Kaaba.

Even by the early 20th century, little had changed. But the advent of air travel and fast passenger jets transformed Hajj. A journey of many weeks was now just a few hours in air-conditioned comfort.

Photos from the 1960s show Makkah and the Grand Mosque almost overwhelmed by the number of pilgrims. By the 1980s, nearly a million were coming every year.

Over the past 60 years, the Saudi Arabian government has greatly expanded the Grand Mosque, most notably beginning in 2008. The mosque’s capacity has been increased from 700,000 to 2.5 million, with Kaaba now surrounded by elevated walkways.

More minarets were added, raising the total to 11, the mosque itself was expanded to become multilevel, to accommodate more worshippers in a safer way. Air conditioning, drainage and heated floors for the winter months were installed between 1988 and 2005.

In 2012, the Abraj Al Bait project was completed, with seven high-rise hotels overlooking the mosque, and dominated by the 601-metre Makkah Clock Royal Tower.

That year a record 3.5 million pilgrims attended Hajj, leading to the authorities limiting numbers for the following years.

There have been other improvements. The tents for pilgrims, once scattered around the Mina area, are now air-conditioned and marked by pathways.

The Jamarat pillars, where the Devil is ritually stoned, have been replaced by walls to reduce overcrowding, while the bridge around them has been widened.

Even so, this part of Hajj has remained the most dangerous. Since the 1990s, at least 3,000 pilgrims have died in the crush surrounding the stoning.

Officials must constantly balance the desire of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims to attend Hajj with the practically of how many they can safely accommodate.

Since 2020, this task has been made even more challenging by the pandemic. This year, one million pilgrims will arrive in Makkah, most at the Hajj Terminal at King Abdulaziz International Airport, which for a few days each year can process 80,000 people at one time — four times as many Dubai International, the world’s busiest.

For each of those pilgrims, though, the spiritual journal is as intensely personal as it was almost 1,500 years ago.