Before hotels sprang up around the Grand Mosque in Makkah, pilgrims performing Hajj would stay in residents' homes, often forming bonds that grew into lasting friendships.

“We opened our hearts before our doors for them,” said Noura Al Ahmadi, 70, who is originally from Madinah.

The Al Ahmadi family had a small house in Sha’b Al Magharba, about two kilometres from the holy mosque, but they always kept one room free so they could have the honour of hosting pilgrims.

Families with multi-storey houses transformed them into mini boutique hotels during the annual pilgrimage.

Fatimah Mohamed Soror, 78, grew up with the tradition of hosting pilgrims. Her family, who are originally from Hadramawt in Yemen, had a four-storey house in Al Falaq, only a 10-minute walk from the mosque.

“The attic had two rooms, a kitchenette and a bathroom," she said. "We used to host the pilgrims on three floors, and the whole family would go up to the attic for the duration of Hajj."

All their belongings would be cleared away and carpets rolled out, leaving the two bedrooms and one living room on each floor clear except for a big cupboard that was hard to move.

“We would move all our stuff to the ground floor and lock it in one room; then the three floors would be rented out,” Ms Mohamed Soror said.

It was heavy work, but she and her eight siblings would work hand in hand to get it done before they all squeezed into the topmost floor for almost a month.

She recalls the first time she collected rent on behalf of her father. It was 3,000 riyals, although she cannot remember the exact year.

“I think this was 60 years ago,” she said.

The amount kept growing over the years.

“I remember the last time we rented, for 100,000 riyals before 1984. At that time we had moved out so we rented the whole four floors and the roof for whole Hajj season [a month to five weeks]. A few months after that the house was demolished for a new road that was being built.”

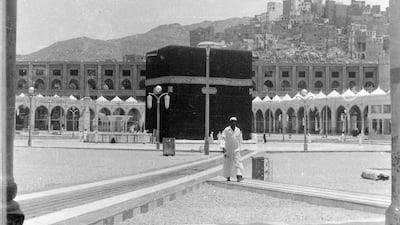

The Grand Mosque has undergone three major expansions since 1955.

The second renovations under late King Fahd were performed gradually between 1982 and 2005, when many old houses around the mosque were demolished to make room.

The remaining houses continued hosting pilgrims until the third round of expansion started in 2008, when more old family homes were demolished. Yet families carry on with the tradition by hosting friends, even for only a few days.

Abdullah Ahmetoglu, 33, remembers running through his grandfather’s and aunt’s house as child with rooms full of pilgrims.

He said he helped the pilgrims with everything during their stay, from guiding them through the Hajj rituals to showing them the best places to eat and to shop for gifts before returning home.

Most of the pilgrims tried to stay at houses of people who might speak their language, as many families in Makkah are descendants of settlers from other Islamic countries.

Mr Ahmetoglu's family is of Turkish and Uzbek descent. His father and grandfather could speak Farsi, Turkish and Uzbek, so the pilgrims who stayed with them were often from Uzbekistan or Turkey.

Some pilgrims would return to the same house over the years, sometimes leading to lasting friendships with the owners.

“Once, a woman and her children stayed in our house and became a close friend of my grandmother,” Mr Ahmetoglu said.

The woman came back for visits over the years, and when she died, her sons continued to visit, he said.

But the visits changed slightly when one of them, Turgut Ozal, became the eighth president of Turkey and had to be accompanied by guards and an official delegation.

It was common for pilgrims to bring goods from their home countries with them, gifting some to their hosts and selling the rest on the streets of Makkah.

Ms Al Ahmadi particularly remembers the gifts.

“The Indonesians used to get sarongs. I also remember an Egyptian lady who used to get me cotton clothes – it was the best quality of cotton I ever got.'

The interaction with pilgrims was not limited to gift-giving or helping them when needed.

Female pilgrims would go up to the roof or to the women's room of the family they were with for some tea, ma'amul and chats. Although language was sometimes a barrier, hand gestures would do.

“Every day they would come up and we would prepare tea and some sweets and nuts. We would talk via hand gestures and sometimes they would use our kitchen to cook," Ms Mohamed Soror said.

She vividly remembers the smell of saffron-scented Iranian rice.

Her neighbours, the Khawandanah family, used to host Iranians as well. Their daughter Nadia, now 57, and her cousins used to ask the women to teach them new words.

“My father spoke more than 10 languages as he was a trader interacting with a lot of pilgrims," Ms Khawandanah said. "As children, we saw those pilgrims staying over as a chance to learn from the ladies, to be like my father."

This intense interaction with pilgrims, and hosting people from all walks of life, has shaped the community of Makkah residents.

“Growing up in Makkah is like being in the United Nations,” Dr Hussain Ghanam, 64, said of growing up exposed to different nationalities, cultures and careers.

Hajj also made Makkah’s residents more open to people and accepting of new things.

“We learnt a lot from these pilgrims,” Dr Ghanam said. “For example, it impacted our cuisine – the Makkawi dishes now includes Indian, Bukhari and Indonesian dishes.”

The tradition of hosting pilgrims faded with the spread of hotels. Some families tried to hold on to it till a decade ago, but the Ministry of Hajj and the Authority of Civil Defence list long safety requirements that pushed many to stop.

However, some families keep old bonds alive by hosting the pilgrims for a short time. The Ozal grandchildren still stay with Mr Ahmetoglu's family for two or three days before going to a hotel, he said.

“They loved us, and we loved them, too,” Ms Al Ahmadi said.